COMMENTARY

FLOC leader keeps fighting the good fight

6/1/2014

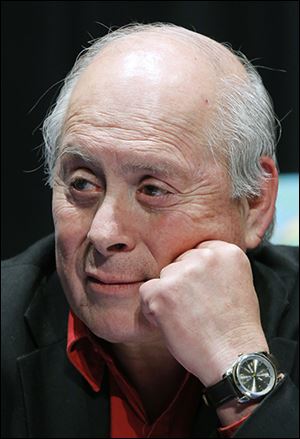

Baldemar Velasquez was tired. I could hear it in his voice.

But he was also elated. I could hear that too.

He was in North Carolina and had just come from a meeting with R.J. Reynolds tobacco executives. “We are making real progress,” he said.

After all, “it took us five years to get the first meeting with these guys.”

His cause is the one that has animated and sanctified his whole life — justice for migrant farm workers.

The campaign of the moment? Ending the exploitation of children, some as young as 5 or 6, in the tobacco fields.

He has some leverage. A new report from Human Rights Watch indicts the tobacco companies for this exploitation of children in North Carolina, Kentucky, Tennessee, and Virginia.

Velasquez

Under current federal law, children can work on a family farm, even if the family does not own the farm. And even if their young bodies are subject to nicotine poisoning on tobacco farms. (Nicotine bleeds through clothing and gloves.)

Federal law does not even limit the hours a child may work in the fields.

Tobacco is the crop migrant farmers are paid to harvest in North Carolina.

The attention Human Rights Watch gives this issue will strengthen Mr. Velasquez’s hand in negotiations.

So will the impending visit of members of the British Parliament. Mr. Velasquez met the lawmakers a few months ago while testifying before them in London and invited them to come see the tobacco fields of North Carolina for themselves. A large percentage of RJR is British owned.

But, interestingly, legislation is not what Mr. Velasquez is seeking. A total ban on child labor, he says, would take much needed bread off the table of the migrant families and reduce the migrant work force, not only by taking children out of the fields but by necessitating the divergence of at least one farm worker to supervise the kids.

Mr. Velasquez knows what he is talking about here. He worked the fields himself as a boy. His parents needed the income he brought in.

What he would like to see is something like what he and his organization, the Farm Labor Organizing Committee, achieved in northwest Ohio in the 1990s — Head Start schools, with expanded hours, for migrant kids.

“It’s not pie in the sky,” he said. “We’ve done it.”

These children will always be connected to the fields, because their parents are. But they can be protected from severe health risks and 12-hour days — guarantees afforded to most of this nation’s children in the early part of the last century.

But how, if not by law?

That is what Mr. Velasquez is negotiating, what he was working on with the RJR execs before I spoke with him by phone, and why he is soon traveling to Washington to meet with Philip Morris brass: the right to organize and make labor agreements.

“So long as we have that right,” he told me, “we can draw contracts and protect ourselves. There is no reason for the government to intervene.”

Mr. Velasquez works the same way Gandhi, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and Cesar Chavez did (he walked and worked with the latter two): His adversary across the table is not an enemy but a fellow human being. “There is a human element here,” he says. So he organizes and lobbies one person at a time. He builds his base of support slowly, methodically. He wants not only justice for his people, but reconciliation for all parties. His is a deeply Christian method. Indeed, he is one of the few people I have ever met who can quote Scripture as if he were giving you directions to a destination — no excessive piety, but matter of fact.

There is no doubt that Baldemar Velasquez is out for minds and hearts, not just bodies. One of the first of FLOC’s great victories was against the Campbell Soup Co. The night before I spoke with him, Mr. Velasquez had dinner with the daughter of one of Campbell’s former CEOs — now a FLOC supporter. He wants conversions.

He was anxious to get back to Toledo. He loves his people in North Carolina but is not crazy about the South. “Ever see that movie, The Help?” he asks. And he is working to develop a youth poverty initiative here. “Sometimes I feel like that guy juggling plates on the old Ed Sullivan Show,” he says. Well, that’s a reference that dates a few of us. I’d pick another example from the same era. To me Mr. Velasquez is more like the leader of a wagon train — a lot of people depend on him for practical guidance as well as inspiration. And he doesn’t let them down.

Keith C. Burris is a columnist for The Blade.

Contact him at: kburris@theblade.com or 419-724-6266.