Morsi’s on-the-job education may be Egypt’s best bet

1/27/2013

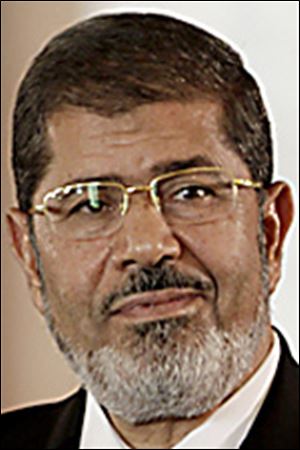

Morsi

KUWAIT CITY — Egyptian President Mohammed Morsi attended an Arab economic summit in Saudi Arabia this month, hoping to encourage investment in his country despite its economic problems and political unrest.

Addressing representatives of a score of Arab states, the former Muslim Brotherhood leader said he opposed France killing terrorists in Mali. But he supported Algeria killing terrorists there, even though 38 hostages died in the attacks.

Such is the dilemma of Egypt’s inexperienced government. Mr. Morsi swept into power unexpectedly in the wake of Egypt’s Arab Spring, which toppled long-time dictator Hosni Mubarak. Mr. Morsi’s government is opposed by democratic forces to its left, tugged at by conservatives to its right, and kept in the shadow of Egypt’s powerful military.

The economy has come perilously close to collapse. Foreign investors have fled. The tourist industry has been crippled. The value of the Egyptian pound has plummeted as people at home have exchanged pounds for dollars, and Egyptians working abroad have stopped sending money home.

Is it time for a new revolution? Economist Mohsen Bagnied doesn’t think so.

The chair of the marketing and management department of the American University of Kuwait has studied the Egyptian economy for 40 years. He developed a road map for Egypt to exploit the peace dividend that was made possible by the 1979 peace agreement with Israel. He has been a consultant to the United Nations and other organizations on marketing and economic development.

Recently, Mr. Bagnied presented a paper in Cairo on economic development in Egypt after the revolution. He also met with several Egyptian cabinet members. He appears frequently on TV and in newspapers as an expert on Egypt’s economy.

Mr. Bagnied draws a distinction between Egypt’s short-term and long-term needs. The long term, he says, should be guided by the “three E’s”: education, ethics, and the economy.

“Egypt ranks very low in terms of its level of development,” he told me. “Forty percent of people are uneducated and live below the poverty level. Corruption is at an all-time high.”

That’s nothing new. Corruption in the government, military, and private business was a hallmark of the Mubarak regime. The jailed leader’s wife and children, Mr. Bagnied says, looted the country to make themselves wealthy.

“Egypt under Mubarak achieved a 7 percent growth rate, which is not bad,” he says. “But it was unbalanced development, and there was a lot of corruption and stealing of that wealth. The rich became much richer, and the poor became much poorer.”

Since the revolution, he says, the system has begun to collapse. Hundreds of factories have shut down. Egyptian and foreign businesses are taking their money elsewhere.

Workers are taking to the streets to demand higher wages. Qatar and Saudi Arabia have lent or given the new regime billions of dollars to avert a currency crisis.

As a result, long-term goals for education, ethics, and the economy have to take a back seat to the short-term need to address what Mr. Bagnied calls the “two S’s”: security and stability. “Without them,” he says, “there is no hope.”

Two views are developing among Egyptians he talks to. One says: Get rid of Mr. Morsi and replace him with a strong leader, perhaps even from the military. Every Egyptian president except one, Sufi Abu Taleb, has come from the military.

The second view says: Give Mr. Morsi a chance. Despite concerns about Egypt’s new — and, some claim, Islamist — constitution, the increasing number of arrests of union activists, and accusations that the Muslim Brotherhood is more interested in consolidating power than in governing, give the Morsi government time to learn on the job.

“The people are not used to democracy,” Mr. Bagnied says. “Most people don’t care about the constitution. They care about having food, having a job.”

Egypt, he says, needs “somebody who is strong, who has a vision and mission for Egypt, and who can give hope and unite the people.” But he doesn’t see anyone like that in the government, the opposition, or the military.

Mr. Bagnied says Mr. Morsi is “a nice guy, but he lacks leadership.” Prime Minister Hesham Qandil, a career public servant and water resources expert, also lacks strength. Still, he says, “the short-term solution is to give the current government a chance.”

“Build the parties, educate them, and I’m sure some new young leadership is going to come up,” he says. “Egyptians know their problems ... but they don’t have the institutions or mechanism to correct them.”

With internal security and economic stability, he says, will come hope.

Kendall F. Downs is a former associate editor of The Blade who lives and works in Kuwait.

Contact him at: kdowns@theblade.com