COMMENTARY

Retired Ohio judge investigated Ruby’s slaying of Oswald

11/17/2013

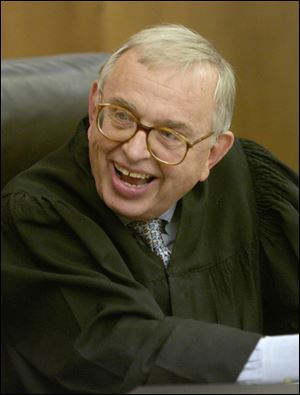

Burt Griffin, who served 30 years as a Cuyahoga County Common Pleas judge, was an assistant counsel for the Warren Commission.

PLAIN DEALER/JOSHUA GUNTER

Marilou Johanek

CLEVELAND — History tapped him on the shoulder 50 years ago. But Burt Griffin, an 81-year-old retired Cleveland judge, remembers it like it was yesterday.

In the fall of 1963 he was barely out of Yale law school and working at a small law firm. His life as a young lawyer was about to change dramatically.

It was Nov. 22, 1963, and Mr. Griffin was working for a small Cleveland law firm. “I was coming back from lunch and getting onto the elevator on the first floor of our office building when someone said that Kennedy had been shot in Dallas,” the judge told me. The office receptionist monitored events on the radio and when word came that the president was dead “we all just left for the day and went home.”

“My initial reaction was that some segregationist opponent of Kennedy had done this to him. People forget but this was a very violent period in the days of the civil-rights movement with all sorts of shootings.”

“But very quickly we learned that [Lee Harvey] Oswald had been arrested and that he was a Marxist and was involved in pro-Castro activities,” said the judge. Like the rest of the country, Mr. Griffin was glued to his television throughout that somber weekend.

“I was watching TV when [Jack] Ruby shot Oswald and was completely appalled thinking it was a terrible disgrace to our country that this kind of thing should have happened,” he said. Ironically, in an unexpected twist of fate, Mr. Griffin was contacted shortly afterward to help investigate the killer of the killer of the president of the United States.

Burt Griffin, who served 30 years as a Cuyahoga County Common Pleas judge, was an assistant counsel for the Warren Commission.

A colleague, who had become an assistant to Robert F. Kennedy, called the surprised Ohio lawyer on behalf of the Warren Commission staff. Evidently the commission wanted investigators who fit a geographic and age criteria as well as a law school and criminal justice background.

Mr. Griffin’s credentials already included stints as an assistant U.S. attorney and Cleveland prosecutor, which made him a perfect choice. Once he was sure his attorney friend “hadn’t dialed the wrong number,” he jumped at the opportunity to serve.

“My feeling was this may be the most important, at least the most interesting thing I’m ever going to do in my life,” he said. The Warren Commission’s investigatory teams were divided into six components, with a senior and junior lawyer.

Mr. Griffin joined fellow Yale law school alumnus Arlen Specter in accepting separate responsibilities for specific elements of the investigation into the Kennedy shooting. Mr. Specter was charged with finding out where the shots that hit the president came from, Mr. Griffin said.

“I was assigned to determine whether Jack Ruby was involved in a conspiracy. That was our total focus. There was no question Ruby had killed Oswald. We all saw it on television. The issue was whether he was involved in some kind of conspiracy to kill Oswald or to assassinate the president.

“Our focus was heavily on the possibility of a foreign conspiracy,” Mr. Griffin added. “This could not be left as an ambiguous, uncertain issue because it could lead us to war.”

Investigators zeroed in on the period from Sept. 26, 1963 — when the Kennedy White House definitely decided the president would go to Texas — until Ruby shot Oswald on Nov. 24, 1963.

Lee Harvey Oswald, assassin of President John F. Kennedy, reacts as Dallas night club owner Jack Ruby, foreground, shoots him at Dallas police headquarters on Nov. 24, 1963. At left is Detective Jim Leavelle.

Ruby was a local Jewish businessman who ran two strip-tease night clubs. He was at the advertising office of the Dallas Morning News, placing an ad for the clubs, when news broke about the president.

He was already upset over a full-page anti-Kennedy ad he’d seen in the paper with a black border and the name Bernard Weisman attached, Mr. Griffin said. Ruby felt the ad was a discredit to Jews and feared that they would be blamed for the assassination.

He became obsessed with finding the mystery man behind the ad (he never did) and following Oswald developments. “In his own mind he became the first conspiracy investigator,” Mr. Griffin noted wryly.

“Ruby posed as a reporter for the Israeli press,” he said, ingratiating himself with reporters mobbing the Dallas police station. “We have a picture of him standing on a table [at a press conference with the police chief, county prosecutor, and prisoner Oswald] holding a notepad and pencil in his hand.”

“We now know that he had a gun in his pocket at the time. If Ruby wanted to shoot Oswald at that time he could have come forward and killed him in front of everybody,” Mr. Griffin said.

But he didn’t. He waited until the next day. According to the Warren Commission investigator, Ruby came to Dallas in the morning, wired a stripper money from Western Union, and walked a block to the Dallas police station.

“Ruby, still posing as a newspaper person, goes down a ramp, [into the station’s basement] in full view of a police officer who’s on guard at the top of the ramp, and maybe two minutes after he’s there and standing in the crowd with other reporters, Oswald is brought in and he [Ruby] shoots him.”

The first thing the gunman said when police asked him why was, “I had to show the world a Jew had guts,” Mr. Griffin recalled. “Ruby thought if someone who is Jewish killed Oswald who killed the president then the assassination wouldn’t be blamed on the Jews.”

Throughout the Warren Commission investigations, Mr. Griffin said cooperation from participating law enforcement authorities was generally very good except when it wasn’t. “I think the CIA and all the other investigative agencies, including the FBI, were totally dedicated to trying to find out if there was a conspiracy,” he said.

“But they were also totally dedicated to concealing how they operated, and the CIA did not want us to know that they were trying to assassinate [Fidel] Castro.”

In a September, 1963, interview published in the U.S. [and presumably devoured by avid newspaper reader Oswald] the Cuban leader threatened to retaliate if the CIA didn’t stop its efforts to kill him and other top Cuban officials.

“We [commission investigators] didn’t think what Castro said was important because we didn’t believe it. If we had known that what he was saying was true and that the CIA was indeed trying to assassinate him that would have been a big area of investigation for us.”

Former CIA Director Allan Dulles, who was silent about the stealth CIA mission, sat on the Warren Commission. In hindsight, commission investigators were stunned and angry. “I think that [the assassination plot] could have affected our conclusions about Oswald’s motives,” Mr. Griffin said.

“We also know that the FBI covered up some information, which actually would have made the case against Oswald even stronger, because they didn’t want us to know they fumbled the ball. We know that on Nov. 11, 1963, 11 days before Oswald shot Kennedy, he went into the FBI office in Dallas and left a threatening and accusatory note to the agent who was responsible for trying to find him.”

“Had we seen that note that the FBI destroyed,” Mr. Griffin explained, “and had we known what the FBI never told us, it would have strengthened our belief that Oswald, at that point, didn’t intend to kill the president. What guy who is planning to kill the president leaves a threatening note for the FBI?”

So what motivated Oswald? “His life had fallen apart [rocky marriage, separation] and he wanted to be a mover of history,” surmised Mr. Griffin. “I also think he hoped that the assassination would be blamed on right wingers in Dallas [anti-Castro, pro-Cuba invasion activists].”

Oswald’s killer, on the other hand, was motivated to be a hero, concluded his investigator. Ruby gave pretrial testimony to Chief Justice Earl Warren only on the condition that a Jew [Arlen Specter] be present to hear what the suspect had to say.

Ruby would be convicted and sentenced to death. He died of cancer in prison a couple of years before his conviction was overturned because of compromising factors, including trial venue and questionable witnesses for the prosecution.

After a three to five month commitment with the Warren Commission, which stretched into nine months, ended, Mr. Griffin returned home. He later served 30 years as a Cuyahoga County Common Pleas judge, concluding his time on the bench in 2005.

Mr. Griffin has occasionally been called to testify at subsequent Kennedy assassination inquiries over the years.

The commission’s investigatory work was an exhaustive if not perfect process, the retired judge reflected. “But I think frankly we know everything that there is to be known.”

“Does it make a difference,” he asked without answering, “or is it just an interesting moment of history?”

Clearly it was a defining experience for one Ohioan who seized the chance of a lifetime a half century ago to investigate the truth of a national tragedy.

Former Judge Burt Griffin will join a panel of legal experts, including Howard Willens, second in command of the Warren Commission staff, at Cleveland State University’s Cleveland-Marshall College of Law at 9 a.m. on Friday, Dec. 6, as part of an all-day program that will focus on legal issues relating to the investigation and a hypothetical trial of Lee Harvey Oswald.

Contact Blade columnist Marilou Johanek at: mjohanek@theblade.com