Ohio hunters trek over onetime Shawnee land

11/18/2012One in an occasional series

BLACKJACK, Ohio — Hunters will descend on the forests and craggy hills of southeastern Ohio in about a week, eager to harvest white-tailed deer during the state’s brief annual gun season.

They will walk the same ground and stalk the same animal that some of Ohio’s first hunters pursued here for millennia.

But for the Shawnee people that made this area part of their extensive range, there were no hunting seasons, no licenses to purchase, and no strict limit on the amount of game you could take.

Hunger determined the time to hunt, a sacred pact with the Creator and his work determined the right to hunt, and need determined the amount of the harvest.

“This was our homeland. We only took what we needed. We did not kill for sport.”

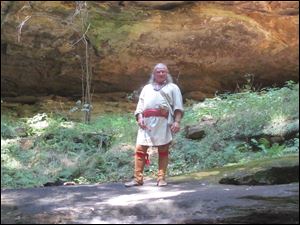

Those are the words of Wehyehpihehrsehnhwah, a Shawnee who shares the traditions and history of his people, who hunted the rugged terrain of the region that today is home to the Wayne National Forest and Hocking Hills State Park.

Wehyehpihehrsehnhwah, a Shawnee, tells how his ancestors hunted in southeastern Ohio and maintained a reverence for the game animals they harvested.

Wehyehpihehrsehnhwah (pronounced Way-u-per-shenwa), who was raised in his grandparents’ home where only Shawnee was spoken, talks about his people migrating here and finding a pristine land rich with game.

“For 10,000 years, not a single ax touched a tree here,” he said. “They grew constantly and became immense in size, with some 300 feet tall that would rival the redwoods. And the streams were pure. The Scioto River was so clear you could see the bottom, and the 200-pound catfish that lived there.”

He relates how the Shawnee saw great herds of elk that they called wapiti, which translates to “white rump.” The forests and gorges also held abundant deer and buffalo, along with the predators — panthers, bears, and wolves.

“There were things that would eat you the first chance they got. It was a very hard land to live in,” he said. “We had to work together, in strong, close-knit communities, to survive.”

A key part of that survival was hunting. The Shawnee raised the “Three Sacred Sisters” — corn, beans and squash — but needed meat for much of their diet.

They used long spears equipped with atlatls, throwing devices, to hunt large game such as the buffalo. Their weapons were tipped with flint, and the ends were rounded, not pointed, so they would not break off if they struck a bone. The Shawnee were proficient at napping flint, or chipping away at it to sculpt a razor-sharp edge.

He said the stories of the lone Native American hunter off in the wilderness pursuing large game animals is mostly a myth. Solitary hunts for deer or elk would take place only in the winter, or in extreme circumstances.

“We learned from our brother, the wolf, how to hunt in packs.

"If we decided to go hunt the buffalo, not one person would go out, because if you struck just one buffalo, it would stampede the others. We would try and separate a small group, or run them into a swampy section and trap them.”

Wehyehpihehrsehnhwah said when the buffalo were plentiful, the Shawnee made good use of the precious resource. Ten buffalo could feed a village of 300 for an entire winter.

Wehyehpihehrsehnhwah said ducks and geese were hunted with bow and arrow, rabbits were caught in snares, and fish in the streams were trapped in nets made of slippery elm bark, or speared.

But it was hunting for large animals that provided for the Shawnee, and they approached it as a spiritual journey, not a sport.

“We believe that there is one great Creator, and that he is life itself,” Wehyehpihehrsehnhwah said. “We believe that he made all things, and left a piece of himself in everything he made. He left spirit, because that’s who he is. We believe that everything around us has spirit and has life — the trees, the plants, the animals and the earth.”

In keeping with that sacred tenant, Wehyehpihehrsehnhwah related a Shawnee story about a hunter who saw the people of his village were sick and hungry, because their crops were not yet ready and their supply of meat was gone.

So he went out into the forest to hunt for deer, but before the hunt he would offer a prayer, not to the Creator, but to the deer.

“Many people mistakenly thought we worshipped the deer, but we did not,” he said. “But we understood that we are just a part of the web of life, as he is. We did not make the deer, and we do not have the right to take the deer. He is our brother.”

So they prayed to the deer, asking it to hear the cries of the sick and the hungry. They pleaded with the deer to take pity on them, and give its life so that many in the village might live.

“I say to the deer that I am going to take your life, but know that your life is precious to me. As I stand over his body and his spirit begins to leave, I will speak to him and promise to never forget the sacrifice he has made.”

The meat from the deer feeds the children of the village, the sick, and the elderly. The hide is used to make clothing, and the antlers provide handles for flint-bladed knives.

And then at the time of his death, the great Shawnee hunter fulfills his prayerful pledge to the deer.

“As they put my body into the very bosom of mother earth, according to the custom of my people, my family will take a tiny acorn and plant it on top of my grave. And from that tiny acorn a great tree will grow. And from that great tree there will be much, much acorns, and then my brother, your children will come, and they will eat the acorns from my tree, and they will live.”

The story summarizes the Shawnee outlook on hunting, and the use of the resources of the earth.

“It is life giving and life receiving, in the beautiful dance of creation.”

Wehyehpihehrsehnhwah, who also goes by the name Ron Hatten, still lives here in what he calls the homeland of the Shawnee people. He uses the large saltpeter caves in the area, carved by ice, wind, and rain from rock that is 350 million years old, as the backdrop when he relates stories of the Shawnee history.

“This was a dangerous place, but still a wonderful place to live, if you knew how to live in that kind of environment,” he said. “My people, when they hunted, they perfected the least amount of effort, for the maximum amount of return.”

He said the Shawnee’s reverent approach to hunting came from a belief that all living things were equal.

“Life is giving to life in a constant motion,” he said. “No one is below or above the other — plants, animals or man.”

Contact Blade outdoors editor Matt Markey at: mmarkey@theblade.com or 419-724-6068.