Why didn't al-Qaeda hit America again?

9/11/2011

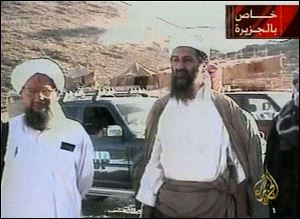

Osama bin Laden is shown at an undisclosed location on Sept. 11, 2001, in this video image released by Al-Jazeera television Oct. 5, 2001. Al-Jazeera did not say whether the image was taken before or after the Sept. 11 attacks on the United States or how it was obtained. At left is Bin Laden's top lieutenant, Egyptian Ayman al-Zawahri. Graphic at top right reads "Exclusive to Al-Jazeera." At bottom right is the station's logo which reads "Al-Jazeera."

WASHINGTON -- Many Americans feared that the Sept. 11 attacks were only the beginning.

It seemed possible that al-Qaeda sleeper cells were hidden in U.S. cities. The media were abuzz with mights and coulds. It was conceivable that the first decade of the 21st century would witness the murder of tens of thousands of Americans.

And some 150,000 people have been killed in the United States since 9/11. But not one was killed by al-Qaeda. Fourteen were killed by its sympathizers: 13 by an Army psychiatrist at Fort Hood, Texas; one by a Muslim convert at a recruiting station in Little Rock, Ark.

How did an enemy that had executed so devastating a strike fail to repeat its lethal success?

Certainly the United States' response abroad and at home was critical. The CIA captured Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, whose imagination had made 9/11 possible, and eliminated most of al-Qaeda's upper ranks. An alert border agent in Chicago turned away a Jordanian who later carried out a suicide bombing in Iraq. British and American intelligence foiled a scheme to blow up airliners bound for the United States. Last-minute police work prevented a former coffee vendor from carrying out his plan to bomb the New York subway.

But another possibility is worth considering: that Americans and their government, frantic in the wake of 9/11, understandably but hugely overestimated the abilities of al-Qaeda. In that sense, 9/11 was both a tactical and a psychological victory for al-Qaeda. Americans reverted to the example of the Cold War. The al-Qaeda threat inherited from the communist threat contained a striking set of parallels: an ideology seeking to impose its will by way of a worldwide conspiracy; a suspected web of underground cells inside the United States; concerns about disloyal citizens.

Such alarm mobilized the government. But it obscured the difference in the scale of the threat: For decades, the Soviet Union had thousands of nuclear missiles aimed at U.S. cities. Even the most generous accounts of al-Qaeda's capacity posited a single stolen nuclear weapon somehow spirited across a border and detonated. "We gave [al-Qaeda] a legitimacy it did not deserve," said Audrey Kurth Cronin, a professor at George Mason University, whose 2009 book, How Terrorism Ends, places al-Qaeda in a long history of violent movements that flared and then faded.

Mohammed might deserve the media tagline "mastermind" for 9/11, but he also approved dubious schemes such as taking down the Brooklyn Bridge with an acetylene torch. Both the Nigerian who tried to bring down an airliner over Detroit and a former financial analyst who tried to blow up Times Square successfully penetrated U.S. defenses, and both had been trained in explosives abroad. But their bombs fizzled.

For an American, the chance each year of being killed by a terrorist is small -- about 1 in 3.5 million, according to John Mueller, a political scientist at Ohio State.

But the brazenness of 9/11 and its execution have stood as an argument that anything is possible. "A lot of scenarios that would have been considered far-fetched on Sept. 10 suddenly became plausible," said Brian Michael Jenkins, a security expert with the RAND Corp. and San Jose State University who has studied terrorism for 40 years. "And there was a fairly relentless message of fear coming out of Washington."

Al-Qaeda or its adherents did mount deadly attacks in Bali, Indonesia; Casablanca, Morocco; Madrid, and London, as well as in Iraq and Afghanistan. Its indiscriminate slaughter of Muslim civilians drove its popularity steadily lower in the Muslim world, but its creed and methods have spread to a few unstable countries. Today, al-Qaeda's branch in Yemen is rated by many experts as a greater threat to the United States than the network's diminished core in Pakistan.

After years passed with nothing approaching 9/11, conservative writers and politicians began to warn of a "stealth jihad" to impose Islamic law on the West. The theories fueled last year's clamor against the Islamic center proposed near Ground Zero in Manhattan.

Then, just months later, the Arab world was shaken by popular demands, not for sharia, but for democracy. Al-Qaeda found itself decidedly on the sidelines. In May came the killing of Osama bin Laden. The image of the graying al-Qaeda founder capped the impression of a group in decline, made increasingly irrelevant by its arid doctrine, its brutal tactics, and the unpredictable course of history.

In July, Leon Panetta, defense secretary and former CIA chief, declared "we're within reach of strategically defeating al-Qaeda." Other officials rushed to refute or qualify the statement, but it marked a striking judgment from a man immersed for years in threat intelligence.

Now, with counterterrorism under the same budget pressure as every other federal program, the blank-check approach of the last decade is certain to change. Ms. Cronin of George Mason says she thinks that's not a bad thing. "The fact that we overspent and now have to cut back will force us to be more strategic," assessing risk with calm resolve and not hype or hysteria, she said.