Woody’s final act in 1978 ended his storied career, memories of Clemson game return for Orange Bowl

OSU players loved coach, regret how his career ended

12/29/2013

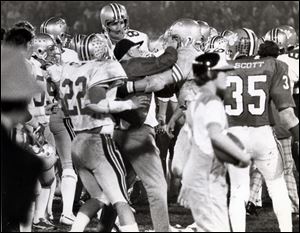

Ohio State coach Woody Hayes is restrained by offensive guard Ken Fritz after he struck Clemson’s Charlie Bauman in the Gator Bowl in Jacksonville on Dec. 29, 1978. Hayes was fired after going 205-61-10 in 28 seasons at Ohio State.

COLUMBUS — Bill Jaco’s voice softens, then cracks.

It will be 35 years this week, and the ghosts of Ohio State’s first and last meeting with Clemson — the night the man he felt represented the best of college athletics became a symbol for the worst of it to a stunned nation — refuse to cede.

"It was probably the worst day for me," Jaco said, pausing. "It really was. A lot of guys, we think about that, we talk about it. It really affected a lot of guys. You didn't want him to go out like that. ... Woody Hayes was the absolutely greatest man I’ve ever met in my life."

Jaco is now an insurance agent outside of Houston, where the 1975 St. Francis de Sales graduate and former OSU tight end settled after a brief stint with the Oilers in the NFL.

When the whims of the BCS paired the Buckeyes and Clemson in Friday’s Orange Bowl, Jaco knew the spotlight would revisit the stained final chapter of Ohio State’s most iconic figure. He was on the sideline when Hayes slugged reserve Tigers lineman Charlie Bauman after a late interception in the 1978 Gator Bowl, ending the coach’s career and cementing a caricature for generations to come.

In Ohio, Hayes remains revered, his explosive temper outweighed by how much he won and how deeply he cared for his players — including their success after football — and university. Elsewhere, he is most known for his famed final outburst.

You will hear a lot about The Punch this week. See it, too. Ohio State fans planted a sign reading, “Charlie Bauman had it coming,” on the statue of Thomas Green Clemson while Clemson fans infiltrated OSU’s campus with a poster mocking Hayes’ right hook.

Yet the legacy of Hayes’ last night on the sidelines — and, of course, of the man himself — goes far beyond the fuming caricature.

Even those involved from Clemson take no joy from their bit role in history.

“He was a good man,” said longtime former Clemson coach Danny Ford, who was just 31 at the time. “I’m sorry it had to happen against us.”

Bauman, meanwhile, has tried to distance himself from the play. Now living in suburban Cincinnati, Bauman did not return a message and has widely declined interview requests.

“Why can’t people let this rest?” he told the Florida Times-Union in 2008. “ ... I don’t have anything bad to say about coach Hayes. He made a mistake. We all make mistakes. I mean, he didn’t hurt me or anything.”

To this day, Jaco believes Hayes meant no harm, putting more of the blame for the ungraceful exit on OSU’s administration.

By 1978, players said Hayes was still the erudite tactician, the military history buff who hammered players on their studies — “If he found out you had a test, he would quiz you,” Jaco said — and lived to “pay it forward.” Everyone has a story about the hours Hayes spent each week visiting sick children in the hospital.

But it was also clear the 65-year-old Hayes was slipping. Jaco said Hayes called him Bill Jobko — an OSU player in the 1950s — while roommate Tim Sawicki’s name became twisted into “Tim Zwiacki.” In one team meeting, Hayes addressed his players as, “Ladies and gentlemen,” before snapping back into place.

Hayes may never have left on his own. Asked three years earlier if he planned to retire, he replied, “Hell, no.”

“When I do,” Hayes said, “I'll die at the 50-yard line at Ohio Stadium.”

“I sure hope the score is in your favor,” a reporter replied.

“If it isn’t, I won’t,” Hayes said.

The 1978 Gator Bowl looked to to be an anticlimactic finale of a long season. After competing for national titles almost every year of the past decade, the Buckeyes entered the game 7-3-1 and ranked 20th nationally.

The end came with freshman quarterback Art Schlichter and the Buckeyes driving for the potential winning score. Instead, with the ball at the Tigers’ 24-yard line and less than three minutes left, Bauman stepped in front of a Schlichter pass and was run out of bounds toward Hayes.

Jaco watched from behind as Hayes grabbed Bauman and slugged him with his right forearm. Nothing infuriated the Old Man more than an interception — much less one that sealed a loss — though players knew something had to be wrong. They point now to Hayes’ diabetes, which he did not strictly monitor.

“He was sick,” said Luther Henson, a former OSU defensive lineman from Sandusky.

Jaco is sure of it.

“He sent the play in with the messenger guard, and he told him, ‘I don’t want to see any interceptions,’ and that’s what he would tell us in practice,” he said. “And if there was an interception, he was mad because he wanted to see the play run right. He would be mad at the defender and hit him.

“I swear I’ll always believe that he totally forgot where he was at. I think he just thought it was a practice for that split second. I’ll go to my grave believing that. It was just sad.”

Hayes left president Harold Enarson and athletic director Hugh Hindman little choice. He was fired the next day.

True to form, Hayes would not apologize, though he did call Bauman afterward. Asked weeks later if he resented OSU, Hayes told reporters, “No, I only carry bitterness toward me.”

“I despise to lose,” he said. “And that has taken a man of mediocre ability and made a pretty good coach out of him. I gave the university about everything I’ve had. I’m only bitter about losing that game we had won. I’ll never take it out on this university. It means too much to me.”

Six months later, Hayes accepted an invitation to speak at the South Carolina High School Coaches Association clinic in Columbia.

“It was standing room only, the biggest crowd they ever had,” Ford said in a news conference earlier this month. “It also was just about the first time that coaches ever came out with beards and mustaches, and he chewed every one of them out that had one.”

Upon his death in 1987, Hayes — who went 205–61–10 and won three national titles and 13 Big Ten championships in 28 years at OSU — left behind a complex legacy.

That is, Jaco said, if you didn’t know the man.

“Woods was the best,” he said. “I could tell you for hours all the things he did for people that nobody knew about. Everything was about helping people, paying it forward.”

In one sense, 35 years after a night that still haunts him and his former teammates, Hayes is a lot like Bauman.

“Maybe someday, this will all go away,” Bauman told the Times-Union. “I hope so.”

Contact David Briggs at: dbriggs@theblade.com, 419-724-6084 or on Twitter @DBriggsBlade.