Stalin’s dacha paints a small life

Dictator built retreat in Sochi to take advantage of mineral spas

2/17/2014

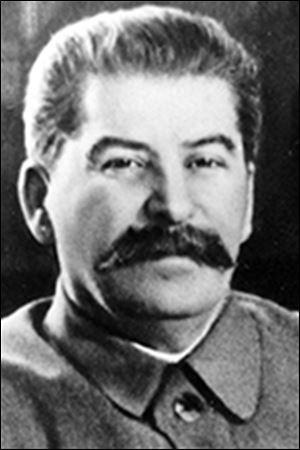

A portrait of Stalin hangs above the fireplace in his dacha in Sochi, Russia, which he built in 1936. The dictator turned the coastal town into a resort hub.

Stalin

SOCHI, Russia — A walk through Joseph Stalin’s summer retreat paints a portrait of life as a very small man. His bed, covered by a pink woolen blanket, is a twin that extends just six feet. The stairs to the second floor are half-steps, set to his specifications. He did not have the booming voice one may expect from a murderous dictator, so the ceiling of the dining room was vaulted to help the sound carry.

A portrait of Stalin hangs above the fireplace in his dacha in Sochi, Russia, which he built in 1936. The dictator turned the coastal town into a resort hub.

The 5-foot, 4-inch Stalin, whom President Harry S. Truman once described as “a little squirt,” was drawn to the Sochi region in the 1920s because of the mineral spas that populated the area. He had many issues with his joints and bones, and the water soothed his aches and pains.

Before Stalin set foot here, Sochi was provincial and mostly unsettled. In the 1930s, as the Soviet Union began a modernization effort that led to the forced labor and mass starvation of millions of peasants, the Russian dictator would invest major capital in turning this majestic coastal city into a resort hub for the North Caucasus and, in 1936, he would build this “dacha” — one of seven vacation homes he had throughout the country.

“He liked this dacha most of all,” said the tour guide, Galina, an Olympic volunteer.

These Sochi Winter Games might be Russia President Vladimir Putin’s baby, but it’s unlikely Sochi would be in a position to host thousands of athletes and fans from around the world without Stalin’s early interest.

“Stalin was a really creative man,” said another tour guide, Anna, with Galina translating. “And he understood the main ideas of the development of the country.”

Said Galina, who works at the Museum of Sports Glory in Sochi, “I think he would have appreciated the Games.”

Stalin was an avid hunter and chess player, so it’s possible he would have appreciated the actual sporting competition. But the spartan nature of his dacha makes it clear that he would not have approved of the lavish spending — a reported $51 billion — it took to put Sochi on the international map.

The home, sitting on the side of a hill overlooking the Black Sea, is large but far from luxurious. That was not Stalin’s way. Only after he died in 1953 did those who maintained operation of the home add the ornate carpets and intricate, colorful tiling to the walls above his personal swimming pool.

Stalin would swim alone in the enclosed, half-oval-shaped pool on the first floor but refuse to visit the sea down below out of fear that someone would see him. Hidden among the trees surrounding his dacha, Stalin enjoyed taking evening strolls. He appreciated the tranquility of Sochi, but, even here, he could not escape the paranoia that stalked him throughout his life, the same paranoia that led to the purging and execution of his rivals.

He had the house painted green so that it could be camouflaged by the foliage around it. He had an unusually tall sofa made so that his body could be blocked from the side, and that wasn’t enough to make him feel safe: He also had the sofa stuffed with horse hair, which he believed would hold up against a bullet.

He was so restless while sleeping that he’d wake up three or four times a night to switch beds. Nobody could know where he was laying his head at a given time.

“He was afraid,” Galina said. “I don’t know, it was some kind of mania.”

Today, the dacha is open to visitors. It’s a surreal experience. Walk in, and you are immediately greeted by a life-size wax statue of the mustached Stalin, staring into space from his desk with a map of Russia behind him and wearing a green military uniform.

For a hefty sum, the private company that manages the dacha will allow people to stay in the rooms where Stalin spent his time or rent out the spacious dining room for an event.

During the Sochi Winter Games, the presidents from Slovenia and Finland have made the half-hour drive from Olympic Park, which is to the south in nearby Adler, to check out the place. But Mr. Putin has never visited, according to Anna and Galina, despite having his own massive mansion — which has been dubbed “Putin’s Palace” — a little more than 6 miles away.

“According to our state, Stalin is a bad man,” Anna said. “He’s not a good figure in our history. Putin can’t come here because of the negative association.”

Standing in the dining room, Galina and Anna discuss their complicated feelings toward the man, who looks down on them from a painting hanging above a fireplace. Stalin had scars from smallpox, but the blemishes, not surprisingly, have been removed from the artist’s rendering.

“He really created a great country, the Soviet Union,” Anna said. “But as for the methods of his power, they are very disputable.”

“Of course,” Galina said, “he wasn’t simple.”

The Block News Alliance consists of The Blade and the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. J. Brady McCollough is a reporter for the Post-Gazette.

Contact J. Brady McCollough at: bmccollough@post-gazette.com and Twitter @BradyMcCollough.