Texting-driving laws hard to enforce

Motorists use phones as police issue few tickets for offense

9/2/2014

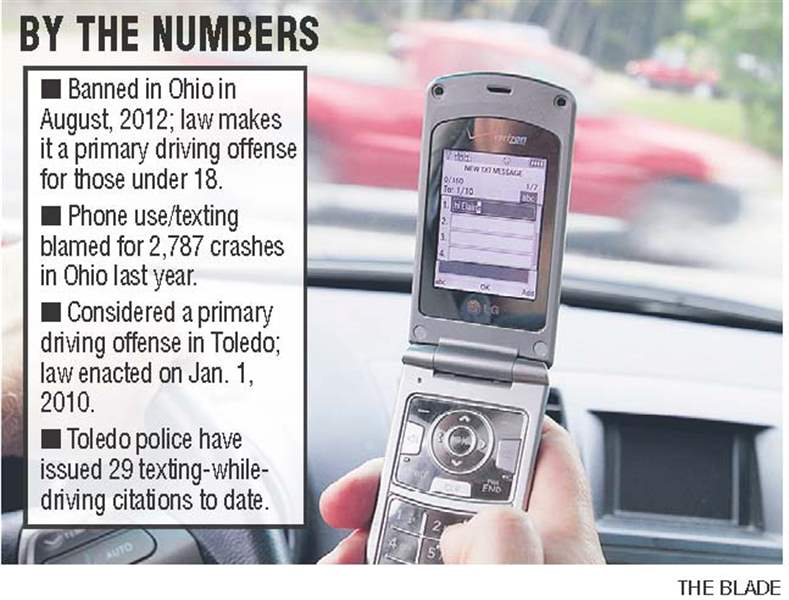

When Gov. John Kasich signed House Bill 99 into law on June 1, 2012, officially banning drivers from texting while driving, many people throughout Ohio rejoiced. More than two years later, it seems those cries of celebration were premature.

Laws against texting while driving are proving to be difficult for police to enforce, and records show they are not improving public safety or discouraging the habit in the way that lawmakers initially hoped.

In Ohio, texting while driving became illegal on Aug. 31, 2012, but a six-month grace period kept officers from handing out anything but warnings until March 1, 2013.

The law applies to adults, ages 18 and older, as a secondary offense, meaning that police cannot pull the driver over unless they have a separate reason to do so, such as breaking the speed limit.

The law is different for drivers younger than 18. For this group, it is a primary offense to use a cell phone or portable electronic device in any capacity, whether texting or making a phone call.

Ohio was the 39th state to implement a statewide ban on texting, but not every Ohio city waited for the state to lay down the law. On Jan. 1, 2010, Toledo became the second major city in Ohio — after Cleveland — to enact its own law.

In Toledo, texting while driving is a primary offense for drivers of all ages. The first violation is a minor misdemeanor punishable by a fine up to $150.

Despite having stricter laws than the state, Toledo leaders have not charged many residents with the offense. Since 2013, Toledo police have issued 29 texting-while-driving citations.

A major issue is the inherent difficulty in proving the use of a cell phone.

“With the expectation of privacy for phones, you can’t look at their phones to see if a text was sent,” said Lt. Craig Cvetan of the Ohio Highway Patrol. “You have to deal with the evidence on hand and observe the violation firsthand.”

But state records indicate cell-phone use behind the wheel is still happening.

According to the Ohio Department of Public Safety, 2,787 crashes in Ohio in 2013 involved a driver distracted by a phone or by texting or emailing. Sixteen of these crashes were fatal. But a state report showed that “because of difficulties in determining cell-phone use or other distractions, distracted driving crashes are likely significantly underreported.”

Of the 29 texting citations issued by Toledo police, only two were issued solely for texting while driving.

Toledo resident Brian Campos, 22, received one of the citations. The charging officer wrote that Mr. Campos was “driving left of center,” which is believed to be how the officer found out that Mr. Campos was texting.

Mr. Campos appeared in Toledo Municipal Court on Oct. 21, 2013, where he entered a plea of guilty and was charged with a $35 fine.

The other citation, given on April 22 to Alexis Chapman, 20, of Holland, reveals more about the challenges surrounding texting laws.

On Ms. Chapman’s citation, the charging officer wrote, “I observed her with phone in hand looking at the phone.” Since she was not a minor, she legally was permitted to use her phone while driving in Toledo, but she was banned from texting.

On May 2, she appeared in court and entered a plea of not guilty. The trial was set for May 28, but the case was delayed. She has not been convicted.

Toledo’s 27 other texting-while-driving citations are accompanied by at least one other offense, including weaving, running a red light, and issues with driver’s licenses.

The only texting citations that involved accidents — three — each involved a citation for operating a vehicle while intoxicated. In such cases, it likely is difficult to determine whether the texting or the intoxication was the cause of the accident, authorities said.

Lyndsie White’s case provides an example.

The 31-year-old Toledo resident had a blood-alcohol level of 0.201 percent — more than the legal driving limit of 0.08 percent — when she was pulled over on Sept. 28, 2013. Additionally, the charging officer cited her for driving without a license, failure to control her vehicle, and leaving the scene of an accident.

The charging officer reported Ms. White’s claim at the time: “She stated that she was texting while driving and that another undescribed vehicle ran her off the roadway.”

For definitive proof, police can request a warrant from a judge in order to obtain the phone records of the driver. But the likelihood of a judge approving such a warrant is questionable at best, experts said.

“It would depend on the circumstance,” said Adam Loukx, Toledo’s law director. “I would be surprised if any judge granted a warrant to prove a person was texting while driving just for a traffic ticket.”

Mr. Loukx said he believes that the chances of obtaining a warrant may increase if texting is the suggested “probable cause for an accident,” but even then it is not guaranteed.

The bottom line, as Mr. Loukx said, is that “if an officer says, ‘I saw a driver with a cell phone or device in front of him,’ that in and of itself would not necessarily mean anything.”

Ultimately, it’s a difficult challenge for officers.

“Quite frankly, unless it’s an extreme circumstance, officers are not going to do that [request phone records],” said Sgt. Joe Heffernan, Toledo police spokesman. “A texting-while-driving violation and a marked-lane violation are the same penalty. They’re both minor misdemeanors.”

In the face of a law that’s difficult to enforce, some police use alternatives.

Some officers prefer education on texting-while-driving instead of direct punishment.

“The goal is to cut down on accidents and to educate,” Michigan State Police Inspector Daniel Pekrul said. “It’s at the discretion of the officer. They can have a roadside conversation or write a citation.”