OHIO POLICY

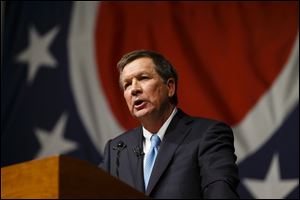

Gov. Kasich wants top income tax to be under 5%

Cost to state is $600 million if everyone gets break

3/10/2014

Gov. John Kasich remains focused on getting Ohio’s highest income-tax rate below 5 percent, but exactly how he would get there remains unclear.

COLUMBUS — Gov. John Kasich remains focused on getting Ohio’s highest income-tax rate below 5 percent, but exactly how he would get there remains unclear.

To drop the tax rate on income earned above $208,500, currently at 5.33 percent, to below 5 percent would likely mean an across-the-board rate cut of at least 6.3 percent, according to the Ohio Department of Taxation. That’s worth about $600 million to the state’s coffers.

That assumes the Republican governor sticks with his past strategy of broad cuts affecting the vast majority of Ohioans, rather than targeting just the top bracket number.

“We can get that tax rate under 5 percent,” Mr. Kasich said during his recent State of the State address delivered in Medina. “Balanced budget. Surplus. Regulatory predictability. Lower cost of doing business. That formula will work, and it is working for our state right now.”

But the proposed cut may also play into the image painted by his election-year critics that Mr. Kasich’s policies benefit wealthier Ohioans at the expense of the middle class.

When his administration unveils its proposals this week, the governor will have some help from income tax revenue growth during the first eight months of the current fiscal year that began on July 1, 2013. To date, the state has collected nearly $281 million, or 5.4 percent, more than it projected.

For all taxes, the state is running a more modest $217 million, or 1.7 percent, ahead of projections.

Mr. Kasich has made it clear he’d prefer to get rid of Ohio’s income tax altogether, frequently comparing the state to the handful of others, such as Florida and Texas, that have no income tax. But absent that, the 5 percent threshold seems to have taken on some symbolic importance.

“In many respects, it’s a PR thing,” said Greg Lawson, policy analyst with the conservative Buckeye Institute for Public Policy Solutions. “The lower it goes, the better it is and the less penalizing it is toward work, investment, capital accumulation, and things like that.

“Every little bit you do matters, but I think getting below 5 percent is symbolic,” he said. “It shows we’re very serious about reducing the income tax. It’s sort of the image of putting out the sign on all roads that we’re getting serious because we’re now below 5 percent.”

Zach Schiller, research director for the left-leaning Policy Matters Ohio, found the fixation on 5 percent to be ironic.

“In 2005, when they passed the 21 percent cut [over five years], why was it 21 percent?” he asked. “Not exactly a round number. It was to get the top rate below 6 percent. That was supposed to be some magical accomplishment. … So now it’s 5 percent.”

Assuming the Kasich administration pursues an even 7 percent cut across all brackets, Policy Matters’ studies suggest the top 1 percent of earners, those earning over $360,000 a year, would get 25 percent of the dollars saved, a tax bill $2,515 smaller on average.

“By contrast, the bottom 60 percent gets 14 percent, or less than one-seventh of the total,” Mr. Schiller said. “This is just in the nature of how an income tax works because it’s a progressive tax.”

For example, those earning between $34,000 and $54,000 would save $48 a year from such a cut.

Ed FitzGerald, the endorsed Democratic candidate to take on Mr. Kasich in November, argues that Mr. Kasich’s priorities are misplaced.

"Ed FitzGerald will prioritize economic growth and security for the middle class ahead of policies that disproportionately favor the very wealthy,” said spokesman Lauren Hitt. “John Kasich's tax schemes only benefit the most well-off, and Kasich fails to adequately invest in middle class Ohioans' most pressing concerns: job opportunities, education, and improving our infrastructure."

The Buckeye Institute generally also wants to see the income tax eventually disappear, but it is withholding judgment on Mr. Kasich’s latest goal until it sees the overall package he proposes to accomplish it. Last year, as part of his second two-year budget proposal, Mr. Kasich proposed a broadening of Ohio’s sales tax base and a hike in the state’s severance tax on shale-oil and natural-gas drilling to help pay for new income tax cuts for individuals and small businesses.

In the end, lawmakers ignored the drilling tax hike, made comparatively minor changes to the sales tax base, and raised the state share of the sales tax rate a quarter-cent, to 5.75 cents on the dollar.

The current two-year budget that took effect on July 1, 2013, included a three-year tax cut—a total 10 percent reduction for individuals across all tax brackets and a 50 percent cut on the first $250,000 earned by small businesses that pay the tax.

It marked a $2.7 billion tax cut after some offsetting from the higher sales tax rate, slight expansion of the sales tax base, and other maneuvers. That was on top of a total 21 percent income tax cut that was started in 2005 as part of a broader reform of individual and business taxes. The final increment took effect in 2011 just before Mr. Kasich took office.

All of Ohio’s neighbors impose a state income tax, and the Buckeye State is in the middle of the pack in terms of its highest bracket. West Virginia’s highest rate is 6.5 percent and Kentucky’s is 6 percent. Michigan, Indiana, and Pennsylvania all have flat taxes: 4.25 percent, 3.4 percent, and 3.07 percent, respectively.

Contact Jim Provance at: jprovance@theblade.com or 614-221-0496.