STATE OF TURMOIL

Ohio agency sinks millions into rare coins

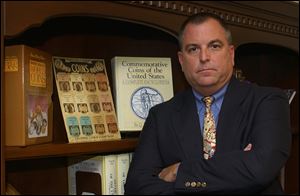

State gives investment business to prominent local republican

4/3/2005

Tom Noe, with Gov. Bob Taft, and Republican National Committee Chairman Ed Gillespie at a 2004 fund-raiser, has given more than $11,000 in contributions to both Mr. Taft and U.S. Sen. George Voinovich, a former governor, over the last decade.

Tom Noe says politics had nothing to do with the state's decision to invest with him. The state trumpets its relationship with Mr. Noe's firm, praising the returns on its investment.

Since 1998, Ohio has invested millions of dollars in the unregulated world of rare coins, buying nickels, dimes, and pennies.

Controlling the money for the state? Prominent local Republican and coin dealer Tom Noe, whose firm made more than $1 million off the deal last year alone.

The agreement to invest the money in rare coins is rare itself: The Blade could find no other instance of a state government investing in a rare coin fund. Neither the state nor Mr. Noe could provide one.

"I don't think I'd be excited to invest in rare coins," Vermont Treasurer Mike Ablowich said. "It's a little unusual."

The Ohio Bureau of Workers' Compensation has continued to be the sole investor in Mr. Noe's Capital Coin funds despite strong concerns raised by an auditor with the bureau about possible conflicts of interest and whether the state's millions were adequately protected.

And the state has maintained its stake in Capital Coin despite documented problems:

- Two coins worth roughly $300,000 were lost in the mail in 2003.

- The firm has written off $850,000 in debt over the last three years to cover a failed business relationship.

- Mr. Noe has loaned some of the state's money to a local real estate business that buys and sells central-city homes. A state auditor could not find documents to prove if the loans were sufficiently covered by the value of real estate that a Capital Coin subsidiary held as collateral.

Since the state first ventured into rare coins, Capital Coin has split $12.9 million in profits with the state, with Capital Coin keeping 20 percent, or nearly $2.6 million.

"It's probably one of the better investments in our portfolio," said Jim McLean, chief investment officer for the workers' compensation bureau - the state agency charged with paying medical bills and providing monthly checks to Ohio workers injured on the job.

Typically putting its billions to work in the stock and bond markets, the bureau decided in 1998 to take a portion of its reserves and invest in rare coins. Among the bureau's holdings: a 1792 silver piece estimated to be worth $2 million as well as 18th century nickels and pennies. One of the lost coins was an 1855 $3 gold coin; there are only two in the world.

The state trumpets its relationship with Mr. Noe, praising the returns on its investment. A few years ago, as the stock market tanked, most of its equity funds lost money. Capital Coin was one of the only funds running positive returns at the time, officials said.

Mr. Noe is well-known in Columbus. Former Gov. George Voinovich appointed him to the Ohio Board of Regents and Gov. Bob Taft appointed him to the Ohio Turnpike Commission. He's now chairman of the Turnpike Commission.

Mr. Noe is a former chairman of the Lucas County Republican Party who has given more than $11,000 in campaign contributions to both Governor Taft and Mr. Voinovich, now a Republican U.S. senator, over the last decade. He has given tens of thousands more to Republican candidates around the state.

He worked hard to get President Bush re-elected last year; as chairman of the Bush team's efforts in northwest Ohio, he frequently talked with Karl Rove, one of the President's top advisers.

The administrator of the Bureau of Workers' Compensation, James Conrad, was appointed by a Republican governor, Mr. Voinovich, and reappointed by Governor Taft. All five members of the bureau's oversight commission also were appointed by Republican governors. Mr. Conrad declined several requests for interviews with The Blade.

When reached for comment yesterday, Mr. Taft's press secretary, Mark Rickel, said the governor would not answer questions or comment on The Blade's article.

Jeremy Jackson, press secretary for the bureau, said there is no evidence that politics played any role in the selection of Capital Coin.

Mr. Noe also said politics had nothing to do with the bureau's decision to invest with him.

"This had to do with Tom Noe, the coin dealer," Mr. Noe said. "It had nothing to do with politics. If someone tells you that they got involved on my behalf to help me on this politically, then they're lying to you."

His knowledge of coins led Ohio officials to make him chairman of the state's commemorative quarter committee. He's also the current chairman of the U.S. Mint's Citizens Coinage Advisory Committee, which advises the Treasury secretary on coinage.

Market 'ripe' for coin fund

Since he was a boy growing up in Bowling Green, Mr. Noe, 50, has been fascinated by the coin world; as early as 12, he was running coin shows. After less than a year at Bowling Green State University, he dropped out of college to pursue the business full-time.

His business, Vintage Coins and Collectibles on Briarfield Road in Monclova Township, has done well and helped make him a comfortable living. He and his wife, Bernadette, who like Mr. Noe is a former chairman of the Lucas County Republican Party, own a $480,000 condominium on the Maumee River, a $600,000 home on Catawba Island, and a $1.85 million waterfront home in Key Largo, Fla. Ms. Noe is a local attorney.

In the 1990s, Mr. Noe started to think about creating a coin fund in which private investors would pool their money with him.

He shared his idea with others and drafted a proposal for private investors.

Then, in 1997, he said he got a call from someone - whose name he could not recall - who was aware of the bureau's intent to create an "emerging-managers" program. The bureau was going to consider alternative investments in addition to its traditional focus on bonds and stocks.

Mr. Noe said he made a phone call, got a questionnaire from the bureau, and returned a copy of his proposal for private investors. Intrigued, the bureau asked him to talk about his proposal. He agreed.

"I don't think anyone can sell a coin deal better than I can sell a coin deal," he told The Blade recently.

More than 100 firms from all over the country wanted a piece of the emerging-manager action, which would include nearly $500 million of the bureau's $18 billion investment portfolio. The prospective money managers offered their services to invest in stocks, bonds, private equity, and other financial instruments.

Bureau staff then interviewed all of the firms and graded them based on their size, their staff, and their prior returns. Capital Coin, however, was not graded, officials said recently, because there were no similar managers to compare it with.

In March, 1998, the bureau's oversight commission approved a list of 28 managers for the program, including Capital Coin, and by August, it had received its first $25 million. Only four other managers got as much or more. The bureau later granted Capital Coin an additional $25 million, the bureau's self-imposed cap. Only two other fund managers in the emerging-manager program have as much.

Arrangement scrutinized

On the surface, the state's arrangement with Capitol Coin is fairly simple. Mr. Noe and his partners take the state's millions and, using their decades of expertise, buy coins and resell them, hopefully at a profit.

At the end of each year, the profits are split 80-20 with the state. Mr. Noe said his cut goes to his firm, Thomas Noe Inc., which then must pay expenses. Mr. Noe is president of Thomas Noe, Inc., and one of its shareholders.

The Capital Coin arrangement was in place for about a year before it caught the eye of the bureau's audit department. It soon launched a review of the deal because of "the unique nature of the investment." It is the only internal review performed on any of the emerging-manager firms, the bureau has told The Blade.

In his review, Keith Elliott, manager of internal audits for the bureau, broached a number questions:

- Should the managers of the fund be allowed to personally buy and sell coins to and from Capital Coin? Was that a conflict of interest?

- Are the mortgages that Capital Coin held adequately supported by the value of the real estate?

- Should Capital Coin pay advances to partners in advance of profits from coin deals that had not yet occurred?

After a flurry of e-mails between Mr. Elliott and others in the bureau, Robert Cowman, the former chief investment officer for the bureau, became aware that Mr. Elliott had expressed concerns. He wrote to bureau chief legal officer John Annarino.

"Keith seems to be questioning the investment merits of this partnership, plus he seems to be questioning the adequacy of the legal document," wrote Mr. Cowman, who was still with the bureau then. "I'm not sure he should be questioning either issue."

Last week, in a phone interview, Mr. Cowman said the bureau fully supported Mr. Elliott's review. "We just wanted to make sure there were the proper controls in place for anything that might come up," he said.

James Conrad is the administrator of the Bureau of Wokers' Compensation, which is investing state funds in rare coins. He declined several interview requests.

At several points in his memos, Mr. Elliott made it clear that he felt that any problems with the fund could lead to problems for the bureau. Some of the practices of Capital Coin, he wrote, "could potentially expose both BWC and the fund managers to adverse public scrutiny regarding the appropriate use of state funds."

One of the most long-standing issues was whether the state could have an independent appraisal done of its coins - letting the state know, in essence, if Capital Coin was doing what it said it was. But Mr. Noe felt that an audit could potentially compromise the partnership by revealing to the coin market what he had purchased for the state.

In one of his memos, Mr. Elliott addressed what could happen if the state did not have an independent inventory or audit: "While we can say we trust the integrity of the manager and that their ability to continue to do business with us in the future ... as a control, this would not help the Chief Financial Officer, Chief Investment Officer, or the Administrator if we have a fraudulent act and they have to go before the press to explain what controls we had in place to prevent the act."

Ultimately, Capital Coin agreed to provide a yearly inventory of coins. However, the state, saying the inventory is a trade secret and not a public record, declined to release that inventory to The Blade.

In his review, Mr. Elliott raised another issue: Was there enough insurance to cover the inventory?

"While [Capital Coin] has $15 million-plus in coins, the partnership only has approximately $6 million in insurance coverage and it was not clear if this coverage covered coins at joint venture locations,'' Mr. Elliott wrote about the state's investment with Mr. Noe in May, 2000.

Mr. Jackson, press secretary for the bureau said the agency was satisfied when Mr. Noe explained that the insurance coverage exceeded the "value of the inventory at any one location in any one given time."

In his memo, Mr. Elliott wrote that Mr. Noe's position on insurance coverage was: "As long as all four locations don't get hit exactly the same time, should be okay."

Mr. Noe said the companies he controls have joint ventures with dealers all over the country. He said the coins are stored in Ohio, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Minnesota, Colorado, and California.

The bureau's review ended in early 2001 with Mr. Cowman sending a letter to Mr. Noe requiring changes in the way the funds were operated. Among them:

- Capital Coin would no longer grant advances to partners against future profits.

- The state would maintain a list of all collateral -- like real estate, coins, and other assets -- received by the fund.

- Coins would be purchased at wholesale prices or lower.

Rare coins go missing

In many cases, Capital Coin uses wholly owned subsidiaries, with names like Rare Coin Alliance, Visionary Rare Coin, and the Spectrum Fund, to buy and sell coins. Capital Coin provides the initial capital and hires an outside manager to run the subsidiaries.

One of the subsidiaries is called Numismatic Professionals, and last year Capital Coin let the state know about a potential problem with it: an employee misappropriating assets.

In an interview, Mr. Noe would say little, except to say Capital Coin is studying the business deals of its subsidiary. He said that review is unrelated to two coins that Mike Storeim, manager of Numismatic Professionals, reported lost in October, 2003.

Mr. Storeim, who works out of an office in Evergreen, Colo., used state money Mr. Noe had given him to buy the coins for about $185,000, he said. The market value of the coins was about $300,000, he estimated.

One was an 1855 $3 gold coin, the other an 1845 $10 gold coin.

The coins were being sent by Express Mail from a professional grading company in California, which certified the quality of the coins, to Mr. Storeim. When he got the package, he said it appeared that it had been tampered with.

After opening it, he found the two coins missing. He contacted Mr. Noe within minutes and later filed a report with the Jefferson County, Colorado, Sheriff's Department.

Ultimately, the sheriff's department ruled that it couldn't determine how the coins were lost and closed the case, a department spokesman said.

"I'm just guessing it was bad luck," Mr. Storeim said. "Sooner or later the coins will turn up. They are completely identifiable."

Mr. Noe told The Blade last week that he accepts the explanation for the lost state coins. However, both he and Mr. Storeim agree that they have a broader disagreement. Mr. Noe said he hired a forensic accountant to examine Numismatic Professionals, a review that is not focusing on the lost coins.

"There's nothing that's been done," Mr. Storeim said. "I've just been waiting for him to want to just settle this and get behind this, and he's not willing to do it."

Mr. Noe indicated that he is working toward resolving the issue soon.

Subsidiary takes a hit

In his review, Mr. Elliott, the bureau's manager of internal audits, wrote extensively about one of Capital Coin's partners, Visionary Rare Coin. It was run by Mark Chrans, who lives in Southern California and now operates Malibu Coin.

Mr. Noe's Capital Coin had created Visionary, provided the funding for it, and hired Mr. Chrans to manage it. He was paid $12,500 every two weeks - money that would be subtracted from profits on future coin sales. Unfortunately, some of those profits never came.

At first, the relationship worked out for everyone, Mr. Noe said recently.

"He was doing well for a long period of time," Mr. Noe said. "He was way ahead. All of a sudden he hit a bad streak and it went the other way, and we cut it off."

Tom Noe, with Gov. Bob Taft, and Republican National Committee Chairman Ed Gillespie at a 2004 fund-raiser, has given more than $11,000 in contributions to both Mr. Taft and U.S. Sen. George Voinovich, a former governor, over the last decade.

By the time the relationship ended, Mr. Chrans had received $335,076 in advances. He also owed $128,583 on a $250,000 loan from Capital Coin - unrelated to the operation of Visionary - from the funds. It is unclear what the loan was for. Mr. Noe said recently he didn't recall the specifics of the loan.

Visionary also recorded a business loss of $359,646.

All told, Capital Coin reported to the state that Mr. Chrans owed it nearly $835,000, which includes roughly $11,000 in interest.

Mr. Noe attributed much of the loss to bad coin deals. He said Mr. Chrans bought coins that fell in value. "He just made some bad decisions on what he was buying," Mr. Noe said.

Although Mr. Chrans made some payments on the debt, Capital Coin has written off more than $850,000 related to Visionary, according to financial records provided to The Blade by the bureau.

Contacted recently, Mr. Chrans would say little about the deal. He said much of the money written off was interest on the original debt.

"I'd rather not go into it any further," he said. "It's rather pointless."

Deals go beyond coins

Early on, when Capital Coin was sending profits of roughly $775,000 to $1.1 million to the state each year, Capital Coin was keeping from $200,000 to $270,000. That money was then be split evenly between Vintage Coin and Mr. Noe's partners, Delaware Valley Rare Coin Co. Inc., located in the Philadelphia area.

"In the first few years I was in this, I probably didn't make any money at all if you really look at the net effect of time away from my core business," Mr. Noe said.

In the years since, the returns have grown substantially. Last year, profits swelled: Capital Coin sent nearly $5.4 million to the state, keeping $1.3 million. And more than half of that came from the second Capital Coin fund that Mr. Noe set up with the second $25 million the state gave him to invest in 2001. Mr. Noe's Vintage Coin is the sole manager of that fund.

Mr. Noe acknowledged that he turned to other investments when he could not find enough coins to buy and sell.

"I didn't want to sit there with money at 2.5 percent," Mr. Noe said. "It's hard to return that."

He made a substantial profit last year, he said, when he sold shares he held in a real estate investment trust that went public. Capital Coin had bought shares in the trust when it was privately held.

Capital Coin also reported loans to people backed by mortgages. One of them was for $200,000, in which the borrower pays $2,000 a month at 12 percent interest.

Mr. Noe said he was working with a coin dealer from Pennsylvania who needed to have some coins in order to sell them. But Mr. Noe required that he give him some collateral.

"He had to work the coins," Mr. Noe said. "I couldn't have the coins, so I said you had better give me something that is worth the money.

The coin dealer, who Mr. Noe declined to identify, then gave Mr. Noe a mortgage on his own home as collateral.

In an attempt to verify the value of the real estate, The Blade asked Mr. Noe in what Pennsylvania county it was held. Mr. Noe declined to say. He said the release of the borrower's name would hurt his ability to continue doing business with him.

The Blade asked the state for similar documentation, which in 2001 it had required Capital Coin to keep. However, the workers' compensation bureau has said such a release may be a trade secret, an argument Mr. Noe agrees with. If it's considered a trade secret, it could be exempt from Ohio's public records law.

Questions arise

Almost since the beginning of its relationship with the state, Capital has invested state money - totaling nearly $1 million - with controversial Ottawa Hills real estate mogul John Ulmer. Mr. Ulmer's companies agreed to pay Rare Coin Enterprises, one of Capital Coin's wholly owned subsidiaries, 10 or 12 percent on the investment.

Mr. Ulmer takes investors' money and buys homes, often in the lower-income parts of Toledo. He then fixes them and resells them, acting as a private bank that charges interest rates above traditional banks and mortgage companies.

The resulting revenue stream allows him to provide healthy returns to his investors.

But some community activists and Toledo leaders have accused Mr. Ulmer of buying substandard homes for cheap prices and then reselling them to poor buyers who must pay him inflated prices plus high interest rates. Mr. Ulmer has countered that he's helped people with poor credit realize the American Dream and helped rehabilitate neighborhoods in the process.

Mr. Cowman, the former chief investment officer for the bureau and now director of investment for the Ohio School Employees Retirement System, said he knew Mr. Noe had investments in real estate but said they were short term, which he defined as less than a year. He didn't recall the specific investments, saying there were too many managers to know every single investment.

"We pretty well let our managers use their discretion," he said.

Records filed in Lucas County, however, show that the loans to Mr. Ulmer lasted from a year to five years. Capital Coin, through its subsidiaries, still holds three mortgages valued at $352,000 with Mr. Ulmer's companies, although Mr. Noe has not loaned new money to the company since August, 2000.

Also, Mr. Elliott, the bureau's manager of internal audits, raised questions about the mortgages. He said the bureau had no documentation that the loans to Mr. Ulmer were properly covered by the value of the properties listed on the mortgages.

"While the various notes receivable were collateralized by real estate, as evidenced by mortgages, we found no documentation for appraisals or title searches performed to ensure that the property collateralizing the receivables was of adequate value for the loans," Mr. Elliott wrote.

Last week, the state refused to provide copies of mortgage documentation, which the bureau later required from Mr. Noe, citing the potential that they could be considered "trade secrets" and thus exempt from Ohio's public records law.

But a Blade review of the properties in Lucas County revealed that one of the properties was worth far less than the mortgage value.

Capital Coin, through its Rare Coin Enterprises subsidiary, invested $160,000 in July, 1999, with Ulmer-managed Haven Holdings. In return for the investment, Haven granted Rare Coin a mortgage on a parcel just off Airport Highway in Springfield Township that once had a small single-family home upon it.

According to the Lucas County auditor, that land - now vacant - is worth $25,800. Mr. Ulmer's company, Westhaven Group, LLC, bought it in 1999 for $32,000.

Tough times foreseen

For years, the Bureau of Workers' Compensation was a mess, a political backwater that drove employers and politicians nuts. It's funds were unstable, causing insurance premiums to swing wildly.

It's stability is important to Ohio's business community because every employer must buy workers' compensation insurance - designed to cover workers in case of on-the-job injuries or death - from the state. Ohio is one of five states that requires employers to buy from the state. Other states allow third-party insurance and mixed plans.

In the mid-1990s, then-Governor Voinovich sought control of the agency that he tabbed "the silent killer of jobs." He won the battle, appointing Mr. Conrad, one of his most trusted assistants who had gone with him to Columbus from Cleveland, where Mr. Voinovich had been mayor.

In the next couple of years, the bureau was revamped, and its investment policy liberalized to capture higher returns.

The results have been positive. The state insurance fund has grown to $18 billion, allowing the state to give frequent rebates to employers.

But besides playing the stock and bond markets, the bureau got into rare coins. None of the other four states that have a similar workers compensation system have done so, nor have other states contacted by The Blade.

Several were surprised that a state agency would invest in rare coins, pointing to the speculative nature of the investment and most states' need to invest conservatively.

"Are you kidding?" asked Liza Carberry, investment division manager for Idaho. "There's no liquidity in it. We've got to have secure, safe, liquid type of investments."

The state's decision to venture into the rare coin world has another critic: Mike Storeim. Although he's in the business himself, Mr. Storeim wonders why Ohio is.

"Between you and me, I think they're nuts," he said. "I think that everything's great now because the coin business is good, but ... when the coin business turns and it stops being good, it becomes very, very bad.

"And I think when it gets really bad, it's going to be a really bad thing for the state of Ohio in terms of what their $50 million is worth."

Contact Mike Wilkinson at: mwilkinson@theblade.com or 419-724-6104.

Contact Jim Drew at: jdrew@theblade.com or 614-221-0496.