STATE OF TURMOIL

Fund managers ratcheted up political giving

Donations follow BWC contracts

4/19/2005

COLUMBUS -- For years, the state employees who invested money in the Ohio workers' compensation fund walked a narrow, conservative path.

But in 1996, as the stock market soared and bond prices fell, the General Assembly pushed through a sweeping reform with an 11th-hour amendment. No longer would bonds be the main investment vehicle - now the state could pursue stocks, private equity, real estate, and, it turns out, rare coins.

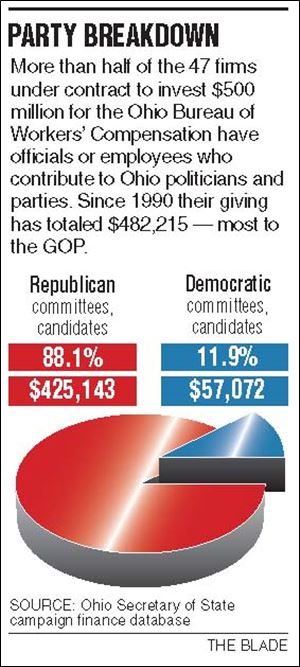

In time, dozens of fund managers would scramble to get a piece of the action. In the process, they got caught up in the Columbus political scene where they became another source of campaign cash for politicians - mostly Republicans.

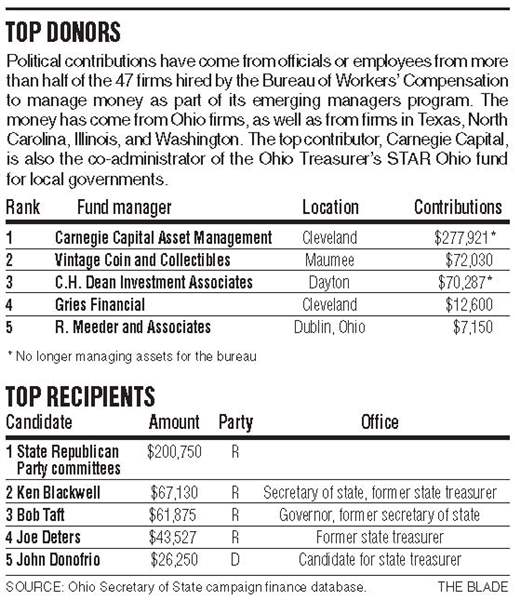

A Blade review of campaign finance databases shows that more than half of the firms chosen by the Bureau of Workers' Compensation to invest $500 million in a new emerging managers fund, contributed to the Republican party and statewide candidates - a kind of Columbus ATM for the GOP.

One of the biggest political givers under contract with the bureau is Tom Noe, a prominent local Republican and rare coin dealer. He was given $50 million by the bureau to invest in rare coins.

The entrance of the bureau's emerging managers program into the Statehouse political world has been profound. In the six years prior to the liberalization of the state's investment policy, more than two dozen firms under contract with the bureau had employees making political contributions.

Those employees gave a little more than $73,000 to candidates for statewide office, or an average of $12,200 a year. In the nine years since getting the bureau's investment business, employee contributions from those firms more than trebled - to $382,000, or an average of nearly $42,500 a year.

The big winners:

●Ohio Republican Party committees, which received $200,750.

●Republican Ken Blackwell, a former state treasurer who is now Ohio's chief elections official, who received $67,130.

●Gov. Bob Taft, who got $61,875.

State Sen. Marc Dann, a Democrat from suburban Youngstown, said yesterday that campaign contributions from employees of the bureau's emerging manager firms to GOP officeholders is "simple, direct, and horrible."

'Pay-to-play'

"It is one thing to have pay-to-play," he said. "I think they are at the point that they don't even know it's wrong anymore.

"As one-party leadership in the state gets more incompetent and arrogant, they get more sloppy," Mr. Dann said.

Jeremy Jackson, press secretary for the Bureau of Workers' Compensation, said there's no link between campaign donations and firms that have received money under the emerging managers program.

The bureau is the state agency charged with paying medical bills and providing monthly checks to Ohio workers injured on the job.

"There's not one place on the [request for proposals] where we ask about someone's politics. What we're looking for are firms that can perform well," he said.

The Blade investigation found there were far fewer campaign dollars coming from firms that were unsuccessful in their bids to manage investment money for the bureau.

Only six of the 67 firms that didn't get the state's business had principals or employees contribute to Ohio politicians or state political parties, according to a search of the state's campaign contribution database by employer.

Those six contributed nearly $55,000. The largest chunk of that - $45,000 - came from one firm, Bartlett & Co. of Cincinnati. That firm has managed money for the city of Cincinnati for years, where it came to know Secretary of State Ken Blackwell, a former Cincinnati mayor. Bartlett also did trading work for the state treasurer's office when Mr. Blackwell was treasurer, said Peter Sorrentino, chief investment officer for Bartlett.

Craig Holman of Washington-based Public Citizen said it's important to know who's giving to whom.

"If a business entity has plans on trying to enter into government contracts, they should not be making campaign contributions," said Mr. Holman, who lobbies for stricter campaign-finance laws on behalf of Public Citizen.

It's unclear how the firms in the bureau's emerging managers program became contributors, and whether they were asked for money or if they volunteered it. Almost every firm contacted by The Blade either did not return phone calls or would not comment on their political contributions.

One who did, Joslyn Berndt Dobson, a former manager of the Palladium Capital Management funds, said she contributed $1,000 to Auditor Betty Montgomery in 2001 at the request of an Ohio-based stock broker who did business with the state.

Ms. Dobson, who at one point managed $20 million for the bureau, has since left the business to raise her children in Austin.

In 2001, she said she got an invitation to contribute to Ms. Montgomery, then attorney general but less than a year away from a successful run for state auditor.

She said she did it because the broker with whom she did business asked, and not anyone directly in politics in Ohio.

Donations no guarantee

Top Republican campaign officials said they get lists of potential donors several ways, including by looking at the same campaign finance database The Blade used for this story.

Mr. Jackson said he's not aware of political fund-raisers asking the bureau for lists of companies that have contracts with the state agency.

Making political contributions doesn't always appear to help.

Carnegie Capital, a Cleveland firm, managed $20 million for the bureau for a few years, but then was fired by bureau officials because of poor investment performance, Mr. Jackson said.

The firm's principals and employees contributed more than $275,000 since 1990 to Ohio politicians - more than $240,000 after it got the contract to manage money for the bureau.

Carnegie also is the co-administrator for the state treasurer's STAR Ohio fund, which manages money for Ohio's municipalities. Last year, the firm was paid $1,252,850 in fees, according to the treasurer's office.

The bureau's emerging manager firms that make political contributions became a bigger source of campaign cash after state law was changed to allow the bureau to invest more aggressively.

In 1994, when then-Gov. Voinovich was running for re-election - and before the investment policy had changed - the firms sent checks totaling $27,800 to candidates.

But four years later, and after the law changed, that amount more than quadrupled to $132,760.

Sharp rise in giving

The increase was sharpest for Vintage Coins and Collectibles, Mr. Noe's company. Mr. Noe and two of his associates contributed $6,780 to GOP candidates and committees in the years before he was given a contract to invest the bureau's money in rare coins. In the nine years since, the three have contributed $65,250 to statewide candidates, nearly a tenfold increase.

Mr. Noe has told The Blade that his contract with the bureau is not politically motivated and that he has made a good investment return for the state, some years better than its stock and bond funds.

State Democrats have decried both the state's deal with Mr. Noe and his political contributions. The state inspector general has agreed to investigate the deal at their request.

Overhauling the state's investment policies began in 1995, when a Republican legislator introduced a bill to give the governor the power to pick the bureau's administrator.

Six years earlier, legislators had turned over power to a 10-member board that was split evenly between business and labor representatives.

Critics had complained that political cronyism infected the bureau's operations, from processing claims from injured workers to updating computer systems.

A 'conflict of interest'

State Sen. Tony Latell, a Democrat from the Youngstown area, made two amendments to the bill that Mr. Voinovich pushed: To give the state treasurer authority over the bureau's investments and to prohibit campaign contributions from fund managers.

"Contributions are a conflict of interest," said Mr. Latell, according to minutes of a May 16, 1995, meeting. But Republicans defeated Mr. Latell's amendments, and the bill became law without them.

In 1996, the legislature approved a bill that expanded the bureau's investment authority. Instead of a long list of approved investments, the bureau would now be guided by the "prudent person" standard.

The bureau has touted the changes in investment policies as an essential part of its renaissance. It now has $16 billion in its portfolio and has often granted rebates to employers.

A decade ago, Larry Gilhousen, an injured worker who lived in the Columbus suburb of Reynoldsburg, accused Mr. Voinovich of pushing for the bureau takeover so his administration could award bureau "contracts for political supporters."

Mr. Gilhousen said last week that he wasn't surprised to learn that the bureau had invested in a rare coins fund controlled by a prominent Republican and that other firms in the emerging managers program had contributed to statewide GOP candidates.

"There's so much money and politics involved," he said.

Contact James Drew at:

jdrew@theblade.com or

641-221-0496.