STATE OF TURMOIL

Ex-coin fund associate has felony record

Man hired by Noe convicted of fraud linked to drug money

4/22/2005

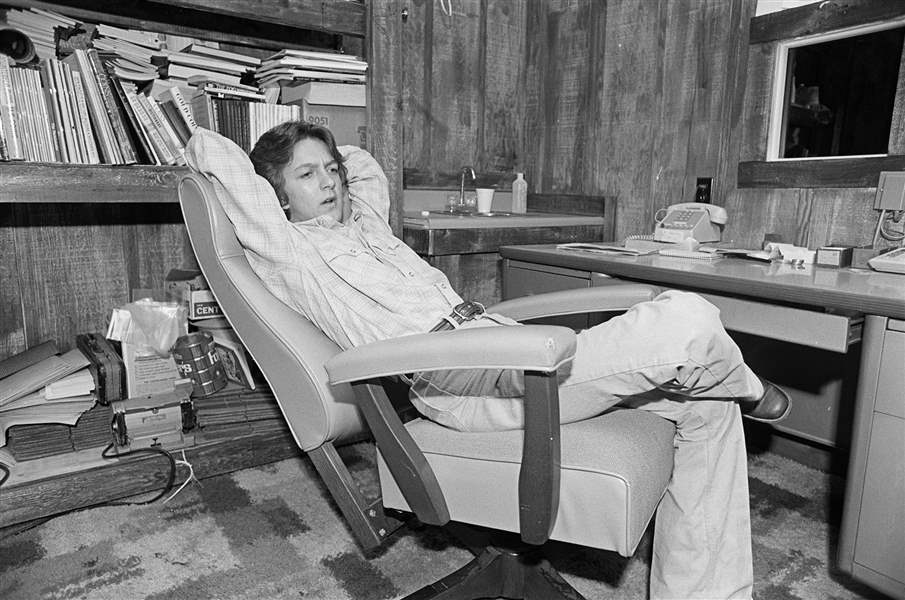

Mark Chrans, at his shop in 1980, was known as a boy-genius in the coin world. Documents show that in 1981 he altered records to make it appear drug money was the by-product of a coin deal.

THE STATE JOURNAL-REGISTER/BARRY LOCHER

Mark Chrans, at his shop in 1980, was known as a boy-genius in the coin world. Documents show that in 1981 he altered records to make it appear drug money was the by-product of a coin deal.

CHICAGO -- One of the managers hired by Tom Noe to buy and sell rare coins for the state was once convicted of faking a coin transaction to cover up drug money, The Blade has learned.

Mark Chrans pleaded guilty to fraud and perjury in U.S. District Court in Springfield, Ill., in 1986. He spent less than a year in a federal penitentiary.

He is the same rare-coin dealer who caused Mr. Noe s Ohio-funded Capital Coin to write off $850,000 in bad debt when he failed in the late 1990s to repay loans and salary advances made to him by Mr. Noe with the state s money, as well as losing more than $300,000 in coin deals that went bad.

According to court documents, Chrans altered business records in 1981 to make it appear that $33,000 in drug money was instead the by-product of a rare-coin transaction.

Federal authorities said Chrans was not implicated in any way in the sale or distribution of the drugs, but he admitted that he knew the $33,000 were drug profits.

Twelve years after he served time in prison, Chrans was brought in as a manager by Mr. Noe to help invest Ohio Bureau of Workers Compensation money in rare coins.

Mr. Noe agreed to pay Chrans more than $25,000 a month in state money to manage the coin venture. Approached before yesterday's monthly Ohio Board of Regents meeting in Columbus, Mr. Noe said he had no idea that Chrans, now 41, had a felony conviction and had done time in a federal penitentiary.

After a string of profanities criticizing The Blade and its reporting about the state s investment in his rare-coin business, Mr. Noe acknowledged that he had not done a background check

on Chrans before handing over to him hundreds of thousands of dollars in state investments.

Mr. Noe, a member of the Board of Regents, repeatedly said he was unaware that he had given state funds to a convicted felon.

I don t know anything about that, he said, raising his voice outside the Regents meeting room before walking away from a reporter.

The Ohio Bureau of Workers Compensation is the state agency charged with paying medical bills and providing monthly checks to Ohio workers who are injured on the job.

Since 1998, the bureau has given $50 million to two rare-coin funds set up and managed by Mr. Noe, a prominent local Republican fund-raiser and rare-coin dealer. Mr. Noe in turn set up subsidiaries and hired other dealers, including Chrans, to manage them. He funded the subsidiaries with state money he received from the bureau.

Chrans won't talk

Contacted on his cell phone yesterday, Chrans declined comment. He would not answer questions about his felony convictions or his business relationship with Mr. Noe, who also is a member of the Ohio Turnpike Commission.

Considered a boy-genius in the rare-coin world, Chrans was 16 when he dropped out of the 10th grade.

He opened a storefront coin shop in the state capital of Illinois, traveled around the country to coin shows, and once claimed to be making $1,000 a week as a teenager.

His success story appeared in People magazine and the National Enquirer, and on NBC s Today show.

In pleading guilty in 1986, Chrans admitted that he laundered $33,000 for a cocaine dealer, Scott Kirk, by converting the drug money into checks drawn on his coin shop in 1981.

In exchange, Chrans received $3,000, court records show.

Chrans met Kirk through an acquaintance who was Kirk s cocaine supplier, according to court records.

Kirk was sentenced to weekends in jail for six months, five years probation, and community service after pleading guilty to income tax evasion charges involving drug sales.

Chrans was convicted on one count of conspiracy to defraud the U.S. government for lying to IRS agents investigating Kirk. The perjury conviction stems from his false testimony before a federal grand jury.

On April 25, 1986, U.S. District Court Judge Richard Mills sentenced Chrans to five years probation for the fraud charge and one year in federal prison on the perjury charge.

The sentence was upheld on appeal. Chrans was released from the federal prison system on Feb. 25, 1987.

Although Mr. Noe said he did not know about the conviction, another of his rare-coin fund managers did.

Leniency sought

Michael Storeim, a Colorado coin dealer who was hired by Mr. Noe to manage another state-funded subsidiary Numismatic Professionals wrote a letter to the federal court seeking a lenient sentence for Chrans.

Mr. Storeim ran the subsidiary, which reported the loss of two rare coins he bought with state money.

Mr. Storeim used state money Mr. Noe gave him to buy two coins for about $185,000 an 1855 $3 gold coin and an 1845 $10 gold coin. The market value of the coins was about $300,000, Mr. Storeim estimated.

In October, 2003, Mr. Storeim reported the coins lost. The coins were being sent to Mr. Storeim by Express Mail from a professional grading company in California, which certified the quality of the coins. When he got the package, he said he opened it and the two coins were missing. Mr. Noe later fired him.

Mr. Noe, in a recent interview, said he accepts the explanation for the lost state coins, but said he hired a forensic accountant to examine Numismatic Professionals, a review that is not focusing on the lost coins.

In a March 25, 1986, letter to the federal court, Mr. Storeim wrote that a prison term for Chrans would only serve to needlessly destroy him personally and professionally.

Mr. Storeim wrote that Chrans had talked to him about the charges and Mr. Storeim claimed that he is guilty of nothing more than juvenile naivete and stupidity; far more deserving of probation than incarceration.

Mr. Storeim identified himself as president and owner of Tangible Investment Professionals of Colorado, based in Denver.

He didn t return messages yesterday seeking comment.

Chrans decision to launder drug money came shortly after the collapse of the coin market in the early 1980s, court documents show.

Mr. Storeim acknowledged Chrans rapid rise to success, along with his rapid decline when the coin market dropped dramatically in 1980.

But Mr. Storeim and others said they had the finest regard for Chrans coin knowledge.

After the Ohio Bureau of Workers Compensation agreed in 1998 to invest in Mr. Noe s Capital Coin fund, Mr. Noe hired Chrans to operate Visionary Rare Coins, a wholly-owned subsidiary of Capital Coin.

Mr. Noe earlier told The Blade that Chrans, like others who run his subsidiaries funded with state money, was hired to buy and sell coins.

But Chrans, who lives in southern California and now operates Malibu Coin, turned into a liability for Capital Coin.

The Blade reported earlier this month that Mr. Noe s coin fund had to write off more than $850,000 from Visionary. It included $128,583 from an unpaid loan to Chrans and more than $335,000 in advances to him that were paid in anticipation of profitable coin deals.

Visionary also recorded a business loss of $359,646 from bad coin deals.

All of the money came from the Ohio Bureau of Workers Compensation given to Mr. Noe s Capital Coin to invest in rare coins.

Mr. Noe said yesterday that Chrans no longer does any business with the rare-coin fund that he controls.

When we severed, we severed. His deal that we had doesn t exist anymore. It has not existed for a couple of years. It just took us a while to get all the coins sold off and take care of it which is why we wrote off the money, he said.

Gov. Bob Taft, who last week defended Mr. Noe s investments in rare coins for the state, was unavailable for comment yesterday, but his press secretary, Mark Rickel, said: Everything with regard to this is currently under review with the Inspector General. The bureau is cooperating fully and will handle any findings in an appropriate way.

Jeremy Jackson, the bureau s spokesman, said yesterday the agency was unaware of Chrans felony conviction when it agreed to invest the first $25 million in Capital Coin Fund in 1998.

As a limited partner, we rely primarily on the investment manager to do business as they see fit. Ultimately, we measure their performance based on their overall returns. To that degree, Capital Coin has done well, Mr. Jackson said.

Asked if the bureau was concerned about Mr. Noe s choice of Chrans to operate the joint venture, Mr. Jackson said: If there is wrongdoing or any other issues, we expect it to come to light with the review of the inspector general s office, and we will deal with them.

Investigation set

Inspector General Tom Charles, in response to a request from Senate Democrats, announced on April 7 that he would investigate alleged wrongful acts associated with the investment practices of the bureau.

Yesterday, deputy Inspector General Arnie Schropp confirmed that the scope of the investigation would include joint ventures set up by Mr. Noe as wholly-owned subsidiaries of Capital Coin.

We re investigating as to how the [Bureau of Workers Compensation] got involved in these types of investments, Mr. Schropp said.

Ohio law prohibits a convicted felon from holding an office involving investment of state money.

According to state law: A person convicted of a felony under the laws of this or any other state or the United States ... is incompetent to be an elector or juror, or to hold an office of honor, trust, or profit.

In an earlier interview with The Blade, Mr. Noe said Capital Coin s relationship with Chrans worked well for awhile.

He was doing well for a long period of time, said Mr. Noe. He was way ahead. All of a sudden he hit a bad streak and it went the other way, and we cut it off.

Although Mr. Chrans made some payments on the debt, Capital Coin wrote off more than $850,000 related to Visionary, according to financial records provided to The Blade by the bureau.

'Some bad decisions'

Mr. Noe attributed much of the loss to bad coin deals. He said Chrans bought coins that fell in value. He just made some bad decisions on what he was buying, Mr. Noe said.

Little is known about the people Mr. Noe hires to run the subsidiaries. Visionary Rare Coins was one of several joint ventures that included Rare Coin Alliance, Numismatic Professionals, and Karl D. Hirtzinger. All were registered by Mr. Noe at his main address in Monclova Township.

The joint ventures were created and capitalized with state money, Mr. Noe has told The Blade. The managers were paid to find and execute coin deals and return the profits to Capital Coin, which would then split them with the bureau.

Outside of notes in financial reports submitted to the bureau and memos written by the manager of internal audits for the bureau, little is known about the joint ventures and how they are run.

When a bureau internal auditor raised questions in 2000 about the rare coin fund, the bureau s chief legal officer John Annarino, wrote: With venture capital investments you are investing in the knowledge and experience of the general partners. The four general partners in this Partnership are all highly qualified professionals in this field. The key point is to remember that if you do not have complete confidence in the general partners, you should not invest in their partnership.

The Blade has a public records request pending with the bureau to obtain information regarding the joint ventures and the arrangements Mr. Noe made with the managers. Mr. Noe has declined to provide that information to The Blade.

In a brief interview in March, Chrans would say little about his relationship with Visionary and Capital Coin. He said much of the money written off was interest on the original debt.

I d rather not go into it any further. It s rather pointless, he said.

Scott A. Travers, a coin dealer and author who is considered a consumer protection advocate in the rare coin business, said a number of coin dealers have felony convictions.

The most common felony offense involves misreporting, underreporting, or failing to report cash sales of at least $10,000 to the IRS, Mr. Travers said. It can amount to illegal money laundering, he added.

The coin field is an easy entry and easy exit field; there really are very few requirements of someone to become a coin dealer.

Consumers should really try and deal with dealers who are members of the American Numismatic Association and the Professional Numismatists Guild, he said.

The coin world tries to police itself through the 50-year-old guild, based in Fallbrook, Calif.

A felony conviction would disqualify someone from being a member, said Tina Shireman, an executive assistant with the guild.

Mr. Noe is a member of the guild. Mr. Chrans is not, according to the 2005 membership guide.

Staff Writer Christopher Kirkpatrick contributed to this report.

Contact Mike Wilkinson at mwilkinson@theblade.com or 419-724-6104.