FREE SPEECH FOR THEE?

Free speech is democracy's greatest safeguard

12/15/2017

Victor Gonzales shouts with a crowd before a speaking engagement by Ben Shapiro on the campus of the University of California Berkeley in Berkeley, Calif., on Sept. 14.

ASSOCIATED PRESS

In a piece published last week by the Washington Post, Pepperdine University political science professor Jason Blakely argued that “free speech absolutists” are endangering democracy.

“A society so awash in racism, xenophobic propaganda, and hateful speech that it could no longer remain together within a civic space would not remain a democracy for long,” Mr. Blakely wrote.

VIDEO: Free speech is the lifeblood of a thriving democracy

Mr. Blakely supports the idea of civic republicanism, which proposes to balance political liberty and rule of law in order to pursue a common good. (It is a concept that influenced the writing of the U.S. Constitution, in that achieving a balance between personal liberty and the rule of law was an overriding concern of James Madison and others, as clearly reflected throughout the Federalist Papers.)

Mr. Blakely argues that civic republicanism mandates we allow institutions — from academic institutions to the federal government — to establish rules that push out “racism, xenophobic propaganda, and hateful speech.” Under this view, government is an agent for cultivating desirable social values and developing a “good” society.

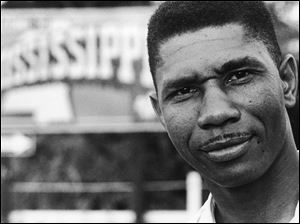

Medgar Evers, the famed civil rights icon, used his First Amendment privileges to promote equal rights and treatment for people of color in America.

The idea of “pushing out” hateful speech appeals to many people, given that the world we live in would benefit greatly from less hate and intolerance. But civic republicanism has profound flaws. It is, in effect, a proposal to expand the role of government, ignoring the widely held view that government is, at best, an unfortunate necessity.

More important, in proposing to curb hateful speech, proponents of civic republicanism like Mr. Blakely are advocating censorship and what would be a dangerous abridgment of First Amendment rights.

To get a clearer sense of what is at stake, let’s take up a couple of key issues raised from Mr. Blakely’s proposal.

First, who will create the rules about which speech is allowed? As Mr. Blakely points out, free speech absolutism is not possible in the U.S., since federal law prohibits speech that would create “imminent lawless action,” including direct threats, as well speech that is perceived to be a public disturbance. Beyond that, however, there are virtually no limitations on speech.

Of equal importance, what constitutes “hate speech” is not precisely defined, and the lack of specificity is a key issue. For example, according to the Public Education Division of the American Bar Association (ABA), “Hate speech is speech that offends, threatens, or insults groups, based on race, color, religion, national origin, sexual orientation, disability, or other traits.”

While it is a definition that was clearly written with care, it does not enable us to identify “hate speech” with any exactness. It is also important to note that the ABA advocates dealing with hate speech by creating laws and policies “that discourage bad behavior but do not punish bad beliefs,” and it opposes laws and policies that define hate speech as hate crimes, or “acts,” citing as the basis of its recommendation two recent cases in the U.S. Supreme Court concluded that acts, but not speech, may be regulated by law.

So, when an academic institution moves to limit “hate speech,” it does so arbitrarily and through an exercise of authority that does not appear to be supported by U.S. law.

Second, Mr. Blakely’s proposal stands squarely in opposition to our history, in contrast to the realities of free speech’s impact on American civic law.

Although many people unfortunately associate free speech advocacy with hatemongers, bigots, and duped liberals, throughout American history free speech has empowered oppressed peoples. Without First Amendment protections, how easily could have individuals like civil rights activist Medgar Evers or suffragist Elizabeth Cady Stanton been suppressed and their ideas along with them?

In fact, even the modest limitations on the First Amendment have frequently been made for highly debatable reasons. Much attention is given to Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes’ argument that some speech — such as shouting “fire” in a crowded theater — can create an unnecessary panic and can be prohibited. What few people know, however, is that Justice Holmes made this claim to justify the ruling of 1919’s Schenck vs. United States, which held that the defendant's fliers opposing to the military draft were not protected by the First Amendment and were criminal in nature.

While this ruling was tempered by the 1969 case of Brandenburg vs. Ohio, this widely cited example of speech limitation was actually motivated by intolerance of anti-war rhetoric. Is this the kind of result we’d welcome with further speech regulations?

For many people, the issue of free speech is a dilemma that they confront when they realize that protecting the rights of people like Mr. Evers and Ms. Stanton also requiring protecting the rights of, say, the Ku Klux Klan or the Westboro Baptist Church. But if institutions pick and choose who has the right to speak (again, a dubious proposition in itself), the door opens for all kinds of censorship.

My patience with Mr. Blakely’s argument wears thin, however, when he invokes Carl Schmitt. Mr. Schmitt was a prominent Nazi jurist, who argued that liberal democracies are unable to defend themselves against ideological opponents because of values like free speech.

Suffragists Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony are photographed in 1870. Without First Amendment protections, vital figures in the women's rights movement could have been silenced.

Is Mr. Blakely right? Are we no longer able to defend ourselves and the country? There can be no doubt that we are under attack, in various ways and from different quarters, but the suggestion that we are unable to defend the country or our system of government is a charge without foundation. Moreover, it would be naïve to assume that our enemies would simply disappear if the U.S. decided, for example, to outlaw Nazism — Germany has outlawed Nazism and yet the ideology is still present.

But invoking a Nazi to argue against the merits of free speech is a cheap trick and an intellectually dishonest one. As is true with most totalitarian regimes throughout history, the Nazis quickly worked to dismantle laws upholding free expression in Germany. By doing so, they were able to eliminate political opposition and use the state to oppress Jews and many other groups.

Liberal democracies are not afraid of free expression. Tyrants, authoritarians, and demagogues are.

There are formidable challenges in upholding the tenants of free speech. But without vigorous protection of the right to free speech, it would have been impossible for American society to progress. There would be no Fourteenth Amendment — ensuring equal protection under the law — and no Nineteenth Amendment — giving women the right to vote.

The late First Amendment advocate Nat Hentoff was fond of writing that free speech is “the right which all others flow.” Without it, nearly all of America’s civic and social progress would have been impossible.

Mr. Blakely’s argument may have come from a good place. But there is no question that limiting speech to topics we find acceptable, politically, or culturally, will ultimately lead to outcomes we all will regret.

In August, the ACLU’s National Legal Director David Cole framed this regret as question. “If we defended speech only when we agreed with it,” he asked in an essay for The New York Review of Books, “on what ground would we ask others to tolerate speech they oppose?”

Mr. Cole’s question shines a light on what makes Mr. Blakely’s essay so misguided. Free speech advocates do not undermine democracy. In fact, the First Amendment is democracy’s greatest safeguard. It enables people of all races, religions, sexual orientations, classes, and beyond to make their case heard.

Examine our country’s social progress over the last 50 years (or the last 225 years, for that matter) and, while imperfect, major strides have been made. The First Amendment made those strides possible. But for the voices of change to be heard, all voices must be allowed to have a say.

Free speech is the lifeblood of a vibrant press, a thoughtful education system, vital religious institutions, and, of course, of a democracy.

In a time of social turbulence, ensuring that all avenues of expression remain open and unabridged will ensure the preservation of our democracy and the promise of progress.

Contact Will Tomer at wtomer@theblade.com, 419-724-6404, or on Twitter @WillTomer.