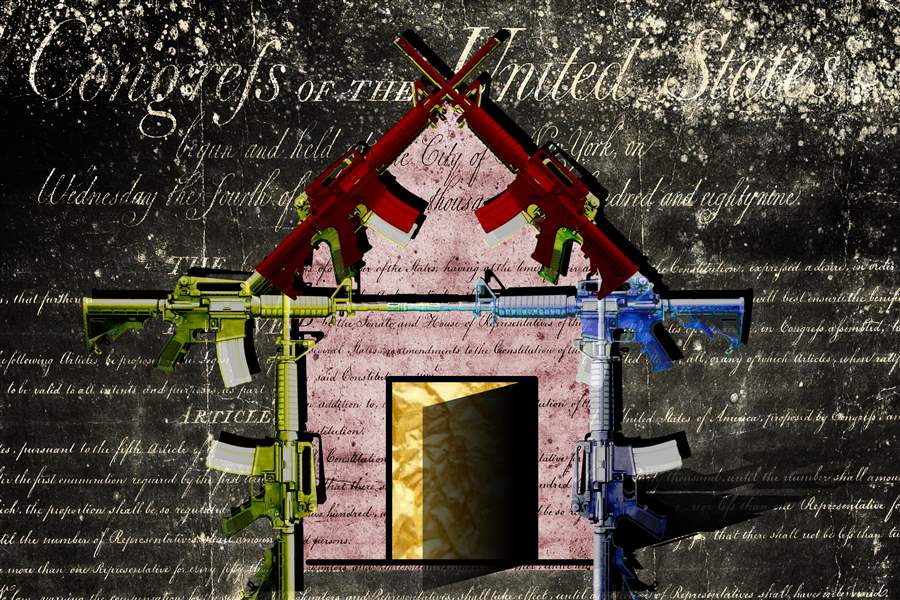

Revisiting the Second Amendment

2/23/2018

THE BLADE/PHILLIP KAPLAN

Buy This Image

Will Tomer

In the wake of the renewed conversation surrounding gun control in America, a colleague asked me if I thought it would be contradictory for a First Amendment advocate to support limitations on the Second Amendment.

After all, no amendment is more important than any other (apart from the 21st Amendment, which repealed the 18th). And if you argue against infringements of the First Amendment, surely you would object to infringements on the Second Amendment, as well, right?

Read last week’s column by Will Tomer

It is true that my appreciation for the First Amendment caused me to reconsider my thoughts on the Second Amendment. Throughout high school and much of college, I allowed my dislike of firearms to cloud my understanding of the right to bear arms — as it currently exists — as set forth in the U.S. Constitution.

I believed that the right to bear arms had been misinterpreted and abused, that the Founding Fathers had intended only for militias, not private citizens, to possess firearms. I even entertained the notion that guns should be outlawed.

However, a closer examination of the historical record reveals a much more complicated set of circumstances and factors, and one which has changed my perspective.

Critics of the Second Amendment frequently point to the language of the amendment: “A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.”

The language, critics argue, indicates that firearms are intended for a “militia,” not for average citizens. They are wrong, however. While the Second Amendment cites the need for a “well-regulated militia” and suggests that the right “to keep and bear Arms” is derived from the necessities of maintaining a “free State,” it does clearly establish the right of individuals to own firearms.

This point of view has been reinforced many times, including by the late Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia’s opinion in the 2008 case of the District of Columbia vs. Heller, in which he wrote that “nowhere else in the Constitution does a ‘right’ attributed to ‘the people’ refer to anything other than an individual right.”

Furthermore, in MacMillan’s Encyclopedia of the American Constitution, the late Don B. Kates Jr., an attorney whose scholarship and litigation have played an important role in defining the contemporary understanding of the Second Amendment, wrote that the framers of the Constitution were deliberate in enshrining the right to bear arms for all citizens. It was one of the few issues on which Federalists, those who supported an empowered federal government, and anti-Federalists, those who supported states’ and individual’s rights, agreed.

The philosophical basis of the Second Amendment is ancient. It was Aristotle who observed that tyrants “mistrust the people, and therefore deprive them of their arms.” It seems clear that defense against tyranny is why the Founding Fathers wanted private citizens to have the right to possess firearms.

However, the Supreme Court’s interpretations of the Second Amendment have not precluded limitations, just as their interpretations of the First Amendment has allowed for some limitations.

Mr. Kates, a gun advocate who represented the National Rifle Association in cases concerned with the constitutionality of various firearm laws, noted that “interpreting the Second Amendment as a guarantee of an individual right does not foreclose all gun controls.”

These reasonable controls, Mr. Kates argued, include prohibiting “minors, felons, and the mentally impaired” from owning a firearm. “Moreover,” he added, “the government may limit the types of arms that may be kept.”

Mr. Kates also wrote that “gun controls in the form of registration and licensing requirements are also permissible so long as the ordinary citizen’s right to possess arms for home protection is respected.”

In other words, even one of the NRA’s most influential legal minds believed there can be reasonable restrictions on the access to firearms, without altering the language or the fundamental intent of the Second Amendment.

With the potential for limitations agreed upon by the Supreme Court and significant pro-gun right advocates, a new crop of questions emerge. If the “mentally impaired” are to be denied the right to own a firearm, as Mr. Kates suggests, how will we define what it means to be “mentally impaired” in relevant legal terms? After all, survey data has found that a quarter of Americans likely qualify for a psychiatric diagnosis. Should a quarter of the country be stripped of their firearms?

Mr. Kates also writes that the government may restrict certain “types of arms,” but what does this mean? Should citizens be limited to the muskets used by the Founding Fathers? Or does the open-ended language guarantee Americans the rights to any arms, including an AR-15?

Critics have been right to point out that strict interpretations of the Second Amendment do protect freedoms, but at a substantial cost. Would reducing the scope of the Second Amendment’s protections actually save lives?

But we must also consider the long-term implications of altering the Bill of Rights. What are the unforeseen consequences of doing so? Could this open the door for the protections provided by other amendments to be reduced?

To close on a personal note, my respect for the Constitution and the rights it bestows on American citizens demand that I support the right to responsibly bear arms. But, as the late Nat Hentoff wrote, I will always be worried “about the Second Amendment coming into my own home.”

Contact Will Tomer at wtomer@theblade.com, 419-724-6404, or on Twitter @WillTomer.