Corker-Kaine bill would codify indefinite detention, endless war

5/11/2018

THE BLADE/WILL TOMER

Buy This Image

In the aftermath of the September 11 attacks, Americans were sold the idea that for the U.S. government to combat terrorism, citizens must be willing to sacrifice their civil liberties. Seventeen years later, the rollback of basic rights, and constitutional obligations in the name of national security continues, with support from both of the major political parties.

A bipartisan group led by Tennessee Republican Bob Corker and Virginia Democrat Tim Kaine has proposed a new Authorization for Use of Military Force (AUMF).

The original Authorization for Use of Military Force was passed just three days after 9/11. The legislation provided the president of the United States with the power “to use all necessary and appropriate force against those nations, organizations, or persons he determines planned, authorized, committed, or aided the terrorist attacks that occurred on September 11, 2001”

Barbara Lee, a House Democrat from California, was the only member of Congress to vote against the bill. Shortly after the vote, Ms. Lee wrote that the AUMF was “a blank check to the president to attack anyone involved in the September 11 events — anywhere, in any country, without regard to our nation’s long-term foreign policy, economic and national security interests, and without time limit.” Ms. Lee was characterized as anti-American at the time by outlets such as the Wall Street Journal and the Washington Times.

Since that time, the AUMF has been used several times, as the basis of the U.S. government’s fight against terrorism, often further damaging civil liberties in the process.

In 2008, the Justice Department successfully argued before the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals that the AUMF is the legal foundation for the National Security Agency’s program of warrantless surveillance. The U.S. Supreme Court refused to hear an appeal on the matter.

In 2012, President Barack Obama signed the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), which contained a section affirming that the executive branch has the authority, under the AUMF, to place those suspected of terrorist activity, including U.S. citizens, in indefinite military detention. Both Mr. Obama and the NDAA’s supporters in Congress defended this provision on the grounds that it reaffirmed the indefinite detention powers afforded to the president under the AUMF.

In thinking about how these powers are actually employed, consider the case of José Padilla, a U.S. citizen who was detained under the AUMF for more than three years without any formal charges.

In 2002, Padilla was arrested at Chicago’s O’Hare International Airport upon returning from the Middle East. He was held as a “material witness” for a month before finally being accused of plotting a radiological, or “dirty bomb,” attack. At that point, he was declared an “enemy combatant” by President George W. Bush’s administration, and transferred to military detention. He stayed there, without formal charges, for more than three years before indicted in 2005 and transferred to civilian jail in 2006. Padilla was eventually convicted, in 2007, of conspiracy to commit murder and fund terrorism, two charges unrelated to the initial accusation of a plot to detonate a dirty bomb. He is serving a 21-year prison sentence.

When Mr. Obama signed the 2012 NDAA, he assured the nation that “will not authorize the indefinite military detention without trial of American citizens,” as President Bush had done.

Mr. Obama did believe, however, that the 2001 AUMF provided the executive branch with the right to wage war against terrorist organizations around the globe, many of which did not even exist on Sept. 11, 2001.

Many commentators have argued that Mr. Obama’s broad interpretation of the president’s power to use military force was unconstitutional. His decision to pursue military action in Libya, Syria, and beyond was seen by critics as an infringement of both Congress’ right to declare, as guaranteed to them under the U.S. Constitution and the War Powers Act of 1973.

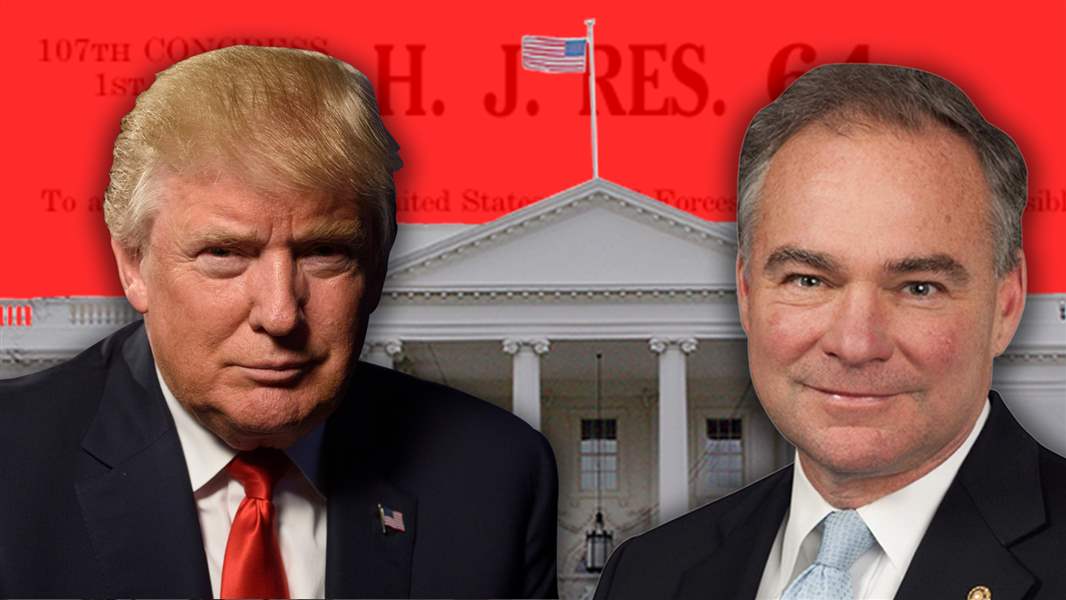

Sen. Bob Corker (R., Tenn.), right, confers with Sen. Tim Kaine (D., Va.) on Capitol Hill. Mr. Corker and Mr. Kaine are co-sponsors of a new Authorization for Use of Military Force.

And so we come to the new AUMF, proposed by Mr. Corker, Mr. Kaine, and four of their colleagues in the Senate.

This legislation, commonly referred to as Corker-Kaine, has been constructed ostensibly to clarify the fuzzy legal standing of U.S. operations in the war on terror. It prohibits attacks on sovereign nations and explicitly lists the terrorist groups against whom the AUMF currently permits military action.

Mr. Kaine has stated that he hopes to reassert Congress’ power to declare war with this new AUMF, putatively addressing the criticism that Congress has abdicated its constitutional responsibility to manage the nation’s war powers.

However, legal experts have been quick to point out that Corker-Kaine will likely exacerbate, not ameliorate, this problem. As Elizabeith Goitein, the program director for New York University’s Brennan Center for Justice, recently wrote: “[Corker-Kaine] would do little more than codify Congress’s abdication.”

While it is true that Corker-Kaine has restrictions on which groups can be attacked and in which countries — provisions which some argue provide greater oversight than the 2001 AUMF — the bill also has loopholes that can be exploited by the executive branch.

If enacted, the legislation will allow the president to add a new enemy group to the list (which could include state sponsors of terror, such as Iran) and report the expansion to Congress.

Under U.S. law, Congress is supposed to authorize the use of military force. Under Corker-Kaine, the president will be authorized to initiate and use military force, while the role of Congress will be limited to stopping military action.

This is a clear upending of the powers outlined by the U.S. Constitution. It establishes a statutory basis for what amounts to perpetual war and forfeits the preeminent authority of Congress in matters of war.

RELATED: President Trump embraces the imperial presidency

Furthermore, Corker-Kaine reaffirms the president’s power to place any person, even a U.S. citizen, in indefinite military detention so long as the president declares that person to be “associated” with one of the explicitly listed groups — a list which, again, the president will be permitted to add to any point.

The ability to detain someone indefinitely and without charges or a trial is a form of tyranny completely at odds with a system of laws based on due process.

The 2001 AUMF and its follow-up amendments and alterations already furnish the president of the United States with powers of questionable legality.

The Corker-Kaine AUMF will only worsen the problem, as it sharply limits the ability of Congress to uphold its constitutional responsibilities where making war is concerned. Of at least equal importance, enactment of Corker-Kaine will further undermine the system of checks and balances that the Framers of the U.S. Constitution believed is an essential element of sound government.

Such a possibility should frighten any U.S. citizen who cherishes the rule of law, and it should raise serious questions among voters about how effectively they are represented on a wide variety of matters, not the least of them being war and peace.

Contact Will Tomer at wtomer@theblade.com, 419-724-6404, or on Twitter @WillTomer.