'Great Train Robber' Ronnie Biggs dies at 84

Infamous Brit crafted image as lovable rascal living the high life in Rio after prison escape.

12/18/2013

This Jan. 25, 2001 file photo shows Ronnie Biggs, one of Britain's most notorious criminals, wrapped in a Union Jack flag, posing for photos with lingerie models Milene Zardo, left, and Francine Mello.

ASSOCIATED PRESS

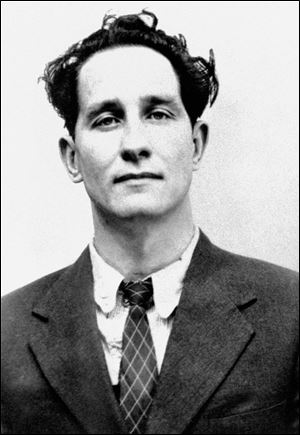

A July 8, 1963 photo of Ronnie Biggs.

LONDON — Ronnie Biggs was a petty criminal who set out to transform his life with the daring heist of a mail train packed with money.

The plan worked in ways he could never have imagined.

Biggs was part of a gang of at least 12 men that robbed a Glasgow-to-London Royal Mail train in the early hours of Aug. 8, 1963, switching its signals and tricking the driver into stopping in the darkness. The robbery netted 125 sacks of banknotes worth 2.6 million pounds — $7.3 million at the time, or more than $50 million today — and became known as “the heist of the century.”

Biggs, who has died aged 84, was soon caught and jailed, but his escape from a London prison and decades on the run turned him into a media sensation and something of a notorious British folk hero.

He lived for many years beyond the reach of British justice in Rio de Janeiro, where he would regale tourists and the media alike with stories about the robbery. He appeared to enjoy thumbing his nose at the British authorities and even sold T-shirts and other memorabilia about his role in the robbery.

He was free for 35 years before voluntarily returning to England in 2001 on a private jet sponsored by The Sun tabloid.

Biggs died today, daughter-in-law Veronica Biggs said. She did not provide details about the cause of death.

Most of the Great Train Robbery gang was caught and sentenced to long terms in jail. Biggs got 30 years, but 15 months into his sentence he escaped from London’s Wandsworth Prison by scaling a wall with a rope ladder and jumping into a waiting furniture van.

It was the start of a life on the run that would hone his image as a cheeky rascal one step ahead of the law.

Biggs fled to France, then to Australia and Panama before arriving in Rio de Janeiro in 1970. By that time, life on the run and plastic surgery to change his appearance had eaten up most of his loot from the robbery.

In all, he spent more than 30 years in Brazil, making a living from his notoriety. For a fee, he regaled journalists and tourists with the story of the heist and offered T-shirts with the slogan “I went to Rio and met Ronnie Biggs ... honest.”

This Jan. 25, 2001 file photo shows Ronnie Biggs, one of Britain's most notorious criminals, wrapped in a Union Jack flag, posing for photos with lingerie models Milene Zardo, left, and Francine Mello.

Biggs recorded a song with punk band the Sex Pistols titled “No One Is Innocent,” wrote a memoir called “Odd Man Out” and even promoted a home alarm system with the slogan: “Call the thief.”

“It’s been a screwed-up life in many respects, but a different life,” he told The Associated Press in 1997. “I’ve never been much of a 9-to-5er.”

Biggs foiled repeated attempts to force him out by deportation, extradition and even kidnapping.

British detectives tracked him down in 1974, but the lack of an extradition treaty with Brazil saved him. When Brazil’s military government tried to deport him, Biggs produced a son Michael with a Brazilian woman and the law again prevented his expulsion.

In 1981, two men posing as journalists grabbed Biggs at a Rio restaurant, gagged him, stuffed him into a duffel bag and flew him to the Amazon River port of Belem. From there they sailed to Barbados, expecting to turn Biggs in and sell their story to the tabloids. But Barbados also had no extradition treaty with England and sent him back to Rio.

At a dive bar just down a winding street from the house where Biggs’ lived in Rio de Janeiro, regulars fondly remembered the fugitive.

“He never talked about the heist,” said Ronaldo Mendes, a 58-year-old photographer who said he often drank draft beers with Biggs.

“He spoke a sort of English-Portuguese, but you could understand him. People liked him a lot, and when he disappeared from Rio it was a surprise to us all.”

Maria do Ceu Narciso Esteves, who owns a grocery store in Rio’s Santa Teresa neighborhood that Biggs frequented for decades, said he “was a good client and a friend.”

“He used to buy his whiskey here, one, two or three bottles, and also ingredients for lunches at home that he served to tourists. That’s how he earned his money,” said Narciso, 77. “He didn’t do anything for free.

“He used to buy here on credit and always paid his bill in the end,” she said. “He was a good person, a polite person and a good client.”

In 1997, Brazil’s Supreme Court rejected an extradition request on the ground that the statute of limitations had run out. At the time, Biggs said he didn’t want to go back to Britain.

“All I have to go back to is a prison cell, after all,” he said. “Only a fool would want to return.”

But within a few years, debilitated by strokes and other ailments, Biggs began to yearn to see England again.

The Sun newspaper helped arrange his return, even chartering the private jet that flew him home. Aboard the plane was Detective Superintendent John Coles of Scotland Yard, who took Biggs into custody with the words: “I am now going to formally arrest you.”

Biggs spent several years in prison, emerging as a frail shadow of his dapper “gentleman thief” image.

Biggs’ lawyers had long argued that he should be released on health grounds, although then-Justice Secretary Jack Straw objected, saying Biggs was “wholly unrepentant.”

Unionized train drivers, mindful that railway man Jack Mills never fully recovered after being hit on the head with an iron bar during the robbery — he died seven years later — also lobbied to keep Biggs behind bars.

Finally convinced that Biggs was a dying man, officials released him on Aug. 7, 2009, a day before his 80th birthday. He had been living in a nursing home since.

In late 2011, Biggs appeared at a London news conference to promote an updated version of his memoir. Unable to speak because of several strokes, he said through his son Michael Biggs that he had come to regret the train robbery and, if he could go back in time, he would now choose not to participate.

Still, he insisted he’d be remembered as a “lovable rogue.”

Not everyone agreed.

“Biggs is not a hero. He’s just an out-and-out villain,” said the train driver’s widow, Barbara Mills.

Biggs had not been one of the ringleaders of the robbery, but he became its most famous participant. The British media remained fascinated with him until the end.

The 50th anniversary of the train robbery this year brought a slew of new books and articles, and the very day of Biggs’ death coincided with a long-planned BBC television show about the crime.

In 2002, Biggs married Raimunda Rothen, the mother of Michael. They survive him, as do two children — Chris and Farley — from his first marriage to Charmian Brent. A third son, Nicholas, died in a car crash in 1971.