New possible sound detected in hunt for Malaysian jet

4/10/2014

A U.S. Navy P-8 Poseidon takes off from Perth Airport on route to rejoin the on-going search operations for the missing Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 in Perth, Australia, Thursday, April 10, 2014. Planes and ships hunting for the missing Malaysian jetliner zeroed in on a targeted patch of the Indian Ocean on Thursday, after a navy ship picked up underwater signals that are consistent with a plane's black box. (AP Photo/Rob Griffith)

ASSOCIATED PRESS

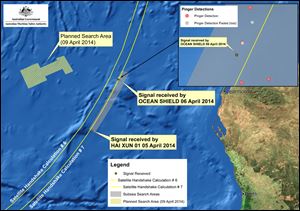

This image provided by the Joint Agency Coordination Centre on Wednesday shows a map indicating the locations of signals detected by vessels looking for signs of the missing Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 in the southern Indian Ocean.

PERTH, Australia — An Australian aircraft hunting for the missing Malaysia Airlines jet picked up a new underwater signal today while searching the same part of the Indian Ocean where earlier sounds were detected that were consistent with an aircraft’s black boxes.

The Australian air force P-3 Orion, which has been dropping sound-locating buoys into the water near where the original sounds were heard, picked up a “possible signal” that may be from a man-made source, said Angus Houston, who is coordinating the search off Australia’s west coast.

“The acoustic data will require further analysis overnight,” Houston said in a statement.

If confirmed, it would be the fifth underwater signal detected in the hunt for Flight 370, which vanished on March 8 while flying from Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, to Beijing with 239 people aboard.

On Tuesday, the Australian vessel Ocean Shield picked up two underwater sounds, and an analysis of two other sounds detected in the same general area on Saturday showed they were consistent with a plane’s flight recorders, or “black boxes.”

The Australian air force has been dropping buoys from the P-3 Orion to better pinpoint the location of the sounds detected by the Ocean Shield.

Royal Australian Navy Commodore Peter Leavy said each buoy is dangling a hydrophone listening device about 1,000 feet below the surface. Each buoy transmits its data via radio back to the plane.

The underwater search zone is currently a 1,300-square-kilometer (500-square-mile) patch of the ocean floor, and narrowing the area as much as possible is crucial before an unmanned submarine can be sent to create a sonar map of a potential debris field on the seabed.

The Bluefin 21 sub takes six times longer to cover the same area as the pinger locator being towed by the Ocean Shield, and it would take the vehicle about six weeks to two months to canvass the underwater search zone, which is about the size of Los Angeles. That’s why the acoustic equipment is still being used to hone in on a more precise location, U.S. Navy Capt. Mark Matthews said.

The search for floating debris on the ocean surface was narrowed today to its smallest size yet — 22,300 square miles, or about one-quarter the size it was a few days ago. Fourteen planes and 13 ships were looking for floating debris, about 1,400 miles northwest of Perth.

A “large number of objects” were spotted on Wednesday, but the few that had been retrieved by search vessels were not believed to be related to the missing plane, the search coordination center said.

Crews hunting for debris on the surface have already looked in the area they were crisscrossing today, but were moving in tighter patterns, now that the search zone has been narrowed to about a quarter the size it was a few days ago, Houston said.

Houston has expressed optimism about the sounds detected earlier in the week, saying on Wednesday that he was hopeful crews would find the aircraft — or what’s left of it — in the “not-too-distant future.”

The locator beacons on the black boxes holding the flight data and cockpit voice recorders have a battery life of about a month, and Tuesday marked one month since Flight 370 disappeared. The plane veered off-course for an unknown reason, so the data on the black boxes are essential to finding the plane and solving the mystery. Investigators suspect it went down in the southern Indian Ocean based on a flight path calculated from its contacts with a communications satellite and analysis of its speed and when it would have run out of fuel.

An Australian government briefing document circulated among international agencies involved in the search today said it was likely that the acoustic pingers would continue to transmit at decreasing strength for up to 10 more days, depending on conditions.

Once there is no hope left of the Ocean Shield’s equipment picking up any more sounds, the Bluefin sub will be deployed.

Complicating matters, however, is the depth of the seafloor in the search area. The pings detected earlier are emanating from 14,763 feet below the surface — which is the deepest the Bluefin can dive.

“It’ll be pretty close to its operating limit. It’s got a safety margin of error and if they think it’s warranted, then they push it a little bit,” said Stefan Williams, a professor of marine robotics at Sydney University.

The search coordination center said it was considering available options in case a deeper diving sub is needed. But Williams suspects if that happens, the search will be delayed while an underwater vehicle rated to 19,700 feet is dismantled and air freighted from Europe, the U.S. or Japan.

Williams said colleagues at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts had autonomous and remotely operated underwater vehicles that will dive to 11 kilometers (36,100 feet), although they might not be equipped for such a search.

Underwater vessels rated to 21,300 feet could search the seabed of more than 90 percent of the world’s oceans, Williams said.

“There’s not that much of it deeper than 6 1/2 kilometers,” he said.

Williams said it was unlikely that the wreck had fallen into the narrow Diamantina trench, which is about 19,000 feet deep, since sounds emanating from that depth would probably not have been detected by the pinger locator.