PARTITION OF INDIA, 70 YEARS LATER

When dawn of freedom gave way to slaughter

8/13/2017

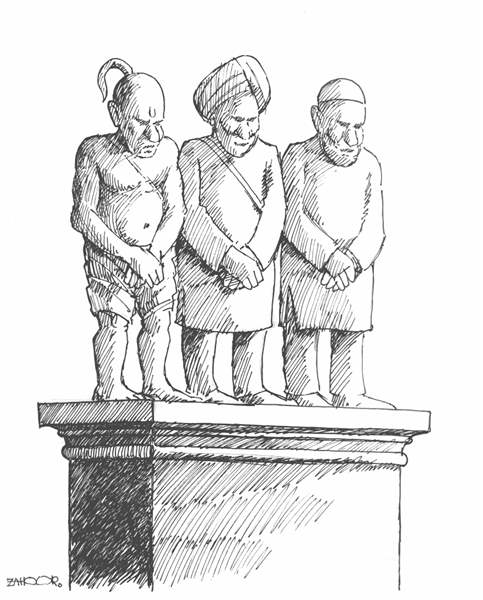

Dr. Hussain proposed a monument at the no-man’s-land at Wahgah crossing between India and Pakistan. The inscription would read: “We are ashamed of what we did to each other during the partition in 1947.” The cartoon was drawn by noted Pakistani cartoonist Muhammad Zahoor.

I remember the hot and humid night of Aug. 13, 1947, when my family huddled around an old Grundig radio to hear the announcement that Pakistan was now a reality.

At the stroke of midnight the radio came alive and announced that the dawn of freedom had arrived. Upon hearing that the whole neighborhood echoed with celebratory gunfire. There was jubilation in the streets and people went around offering sweets to each other. My mother and aunts spread their prayer mats in the courtyard and bowed their heads in grateful appreciation for the miracle of Pakistan.

The euphoria and jubilation, however, was marred by the communal riots that have been happening in all major cities in North India. Our city, Peshawar, was a peaceful frontier town where the majority Muslims had lived in peace and harmony with their Hindu and Sikh neighbors.

Or so we thought. Soon the tranquility of our town was shattered as stories of killings of Muslims in India reached Peshawar. From areas that were to become Pakistan, Hindus, and Sikhs were forced out of their centuries-old homes for a land most of them barely knew and where they had no relatives. Behind that religious frenzy, however, was greed where some locals were going to enrich themselves by grabbing the assets and wealth of the fleeing Hindus and Sikhs.

During that frenzy, armed gangs of vigilantes attacked convoys, caravans, and trains carrying innocent Muslims, Hindus and Sikhs to the safety of their newly created homelands. Trains would arrive at their destination with not a single living person on board. Some people in my hometown of Peshawar decided to settle the score by killing Hindus and Sikhs.

A number of Hindu families lived in our neighborhood of Machi Hatta (now Muslim Meena Bazaar) at the end of a blind alley called Pantan di Gali, or the alley of pundits.

The bloodthirsty hoodlums blocked the narrow alley, looted the valuables, and then set the houses on fire. It was surreal even for a 9-year-old boy to smell the stench of burning human flesh permeating the air. As the muezzin climbed the neighborhood mosque minaret to call for prayers, his chant reverberated in the neighborhood in the backdrop of the billowing smoke. The local people felt helpless against the armed gangs and just stood there in bewilderment and shame.

The drama was repeated in many other Hindu neighborhoods in Peshawar. Some Muslims helped their Hindu neighbors reach the safety of Bala Hisar Fort just outside the western city wall. To escort Hindu and Sikh families to safety was to risk one’s own life.

My elder brother Ijaz Hussain did that many times. Once he put his Muslim turban on the head of a Hindu friend and walked with him hand in hand through the gold market to the city gate and then onto the fort.

There is an old Hindu temple in the narrow alley called Chakka Gali in Karim Pura neighborhood near the Clock Tower.

While the majority of Hindu families made it safely to the fort, one Hindu man didn’t get out in time. He hid in the well in the courtyard of the temple. Every night for week his neighbor, a cobbler, would go to the temple and bring him food. In 1990 while visiting the temple on one of my annual visits to Peshawar, I saw the old cobbler sitting in his tiny hole-in-the-wall shop working as he had done all his life. He did not enrich himself from the misery of others.

There was something terribly amiss in those days. The noble human spirit had turned evil. Religious teachings were set aside in an orgy of wanton killing of the innocent men, women, and children. For many years whenever I was in Peshawar and heard the call for prayers, I would smell the pungent odor of burnt human flesh seeping out of the deep recesses of my brain.

One image has been singed permanently in my mind. We were watching the smoke rising from dozens of burning Hindu properties around the city from our terrace. Suddenly we saw a man on the terrace of a house a few hundred yards from us. He probably had gone up to the outhouse on the terrace when he saw us looking at him. He must have thought we had guns. He froze in in terror and was unable to move. After a few moments he ran off the terrace.

This drama unfolded in many parts of India and Pakistan. The pictures of devastation were unbelievable: scattered bodies of dead people, bloated carcasses of dead animals, caravans of thousands of people inching their way toward the safety of a new country they had not seen, an emaciated infant suckling at the breast of a dying mother and stray dogs gorging on human flesh.

■

Was this holocaust preventable? The question has baffled historians, writers, and thinkers ever since 1947. I believe it could have been prevented.

Ever since the end of World War II the independence of India was front and central for the people of India, for the British had promised them independence after the war. The decision to give independence to India was, however, complicated by the demand for a separate country constituting Muslim majority areas of India. Before ceding to the demand to divide India at independence, the British Cabinet, in a last ditch effort, sent a mission to India in April, 1946. Surprisingly the main parties — the Muslim League and the Congress National Party — agreed to a plan put forward by the Cabinet Mission. It envisioned greater autonomy to provinces within a central government. However, an off-the-cuff remark by Jawaharlal Nehru, the incoming president of the Congress Party and prime minister designate of independent India, scuttled the deal.

But still the catastrophe could have been avoided had it not been for the appointment in February, 1947, of Lord Louis Mountbatten as the new viceroy. He came to India to oversee the independence of India. He set the date of independence in August, 1947, six months after his arrival in India, even though the Indian political parties as well as the Whitehall in London did not expect the independence to be granted before 1948.

Historians agree that the new viceroy should have controlled the communal bloodletting first, arranged for the peaceful transfer of population under the British supervision and then grant the independence.

What followed was a holocaust. Anywhere between 1 million and 2 million people were killed, and more than 10 million people were forced to flee to the safety of their new homeland. The British historian Andrew Roberts, in his 1994 book Eminent Churchillians, puts the massacres of the Partition squarely at the door of Lord Mountbatten. Lord Mountebatten’s collusion with the new Indian government created the volatile issue of the Himalayan region of Kashmir that both countries claim and over which they have fought two inconclusive wars.

■

Despite the trauma of the Partition, the majority of people on both sides of the border have warm feelings for each other. The exceptions are the right-wing Islamic parties in Pakistan and the right-wing Hindu parties in India. Add to the mix an India-centric Pakistani army and a deeply entrenched Indian bureaucracy, and it is next to impossible to bring peace between the two countries.

It is a pity that despite having so much in common between them, the people of India and Pakistan tend to drift apart. The common bonds of culture, music, literature, cuisine, and the arts have been set aside under the influence of religious and political extremism. In Pakistan people are told to look to Saudi Arabia to the west for inspiration. Saudis are the custodians of Islam’s most important holy sites. In the process they tend to forget that their millennia-old roots lie not in the sands of Arabia but in the soil of the Indus Valley.

■

The only land crossing along the 1,800-mile border between India and Pakistan is at Wahgah in Punjab. It is close to the Pakistani city of Lahore and the Indian city of Amritsar. It is at Wahgah that every evening the Indian and Pakistani soldiers enact the drama of lowering the flags that has become a favorite tourist attraction both in India and Pakistan.

The drama of the Partition and the aftermath is beautifully described in a Urdu short story Toba Tek Singh by Saadat Hasan Manto, a Pakistani writer. Soon after the Partition, the story goes, some bureaucrats in India and Pakistan decide to repatriate lunatics between the two countries. Hindu lunatics would be sent to India, and Muslim lunatics would be brought to Pakistan. One patient on the Pakistani side is agitated and refuses to be sent to India. In his crazy mind, why should he go to India when his village of birth was still in Pakistan and the village was not going with him to India? The next day he is found dead, sprawled across the no-man’s-land.

In 2006, I crossed Wahgah on my way to Amritsar, India, where I was going as a visiting professor to teach at Government Medical College. The weight of history still hung heavy on me when I was invited to speak to the Rotary Club. I decided to talk about the Partition.

I told the audience that both India and Pakistan have their own narrative of the Partition and those narratives are opposite of each other. Perhaps it was time that we all come clean on the tragic events of the Partition. I proposed that a monument should be built on the very site where the hero of Mr. Manto’s short story had died. It should have standing figures of a Hindu, a Muslim, and a Sikh with their heads bowed down. The inscription on the monument should read: “We are ashamed what we did to each other at the time of the Partition in 1947.”

My proposal went down like a lead balloon, and subsequently when I broached the idea in Pakistan there were also no takers.

■

The first announcement that we heard from Radio Pakistan at midnight Aug. 14, 1947, declared that the dawn of freedom had arrived. Soon thereafter, in the backdrop of the enormous human tragedy, the famous Urdu language poet Faiz Ahmad Faiz would cry out: “This stained light, this night-bitten dawn/ This is not the dawn we yearned for.”

It is important that we keep telling the story of the Partition until Hindus, Muslims, and Sikhs accept their role in one of the greatest tragedies that befell mankind.

S. Amjad Hussain is an emeritus professor of surgery and humanities at the University of Toledo. His column appears every other week in The Blade.

Contact him at: aghaji@bex.net.