Toledo Museum of Art gets prized Dutch painting

10/4/2011

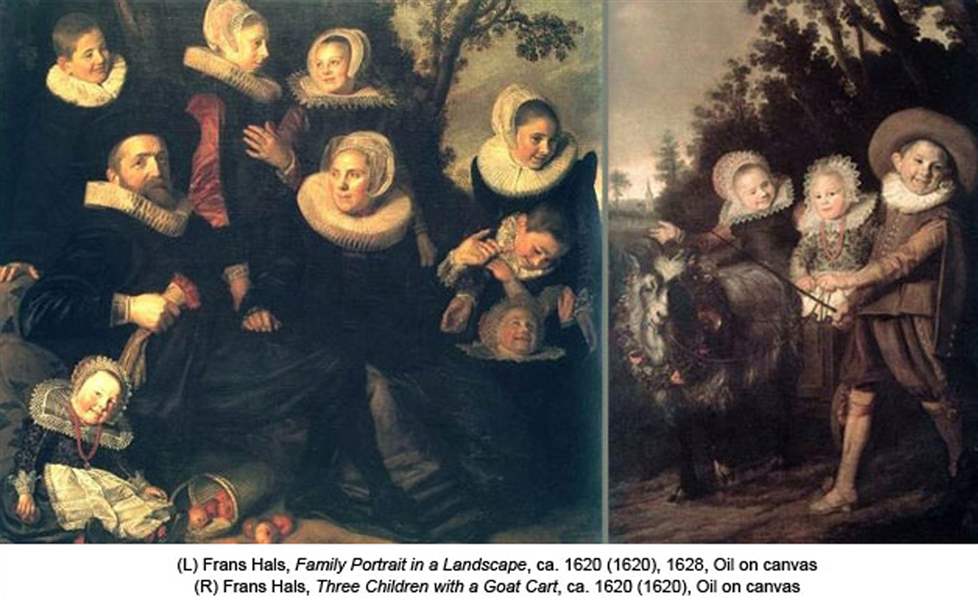

In its original form, ‘Family Portrait in a Landscape’ was much larger than its current 60-inch by 64-inch canvas and featured three more children and a goat. At some point, the painting was divided, and the second portion, at right, known as ‘Three Children with a Goat Cart,’ is now owned by a museum in Brussels.

Editor's note: The acquisition of a 17th-century painting by the Toledo Museum of Art was paid for in part by a gift from the estate of Jill Ford Murray, an heiress to the Libbey Owens Ford glass fortune. She was misidentified in Tuesday's edition of The Blade because of incorrect information provided by the museum.

The Toledo Museum of Art recently acquired ‘Family Portrait in a Landscape,’ a 17th-century painting by Dutch master Frans Hals. Hals is considered second only to Rembrandt among Dutch painters. The museum is to unveil the painting Oct. 13.

The Toledo Museum of Art is enriched by its new acquisition of a large painting of a happy, 17th-century family by Dutch master Frans Hals.

“It’s a strong composition and the way Hals captures the personalities and personal interactions of the family members will delight our visitors,” said Brian Kennedy, museum director.

The seven rosy-cheeked youngsters are mostly merry; their bearded father, a cloth merchant, has pride written across his face, and his wife, her hand on his leg, appears content.

The 60-inch by 64-inch canvas in a splendid new frame is luminous despite a great deal of black paint. Considered by many to be second only to Rembrandt among Dutch painters, Hals (1580 to 1666) was an excellent technician, able to capture subtle effects such as the transparent quality of fine lace and draped fabric. With bold brush strokes, he infused his subjects with remarkable realism, expressive eyes and mouths, and hints of personality — innovations in the 1600s. (The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City is currently showing 13 Hals paintings.)

Family Portrait in a Landscape, found by chance in London, is to be unveiled Oct. 13 beginning with a 6 p.m. talk in the Peristyle Theater by Pieter Biesboer, a Hals expert wo is emeritus curator of paintings at the Frans Hals Museum in Haarlem, the Netherlands. The unveiling is to follow, about 7 p.m. in the Great Gallery. Admission and parking will be free.

The museum does not tell what it spends on art. The highest known price for a Hals sold at auction was $14 million in 2008. The Cleveland Museum of Art paid $12.8 million in 1999 for a Hals portrait of an Amsterdam merchant, dated about 1630, and at the same auction, two other Hals works sold for $3.4 million and $1.4 million.

“We did not pay anywhere near a record price for this work of art,” said Kelly Fritz Garrow, the museum’s director of communications.

The painting was paid for by two sources: the estate of the late Jill Ford Murray, an heiress to the Libbey Owens Ford glass fortune, and money left by Edward Libbey.

Despite his talent, Hals’ work fell out of fashion: He died penniless and his paintings sold for next to nothing. But 200 years later, he was rediscovered by Manet, Courbet, and Monet. Van Gogh was impressed that Hals’ palette had at least 27 shades of black. Americans James McNeill Whistler, Mary Cassatt, and John Singer Sargent were fans of Hals’ technique and vivacity, and that rubbed off on art collectors, especially newly rich Americans such as Edward Drummond Libbey.

In 1908, Mr. Libbey, a founder of the Toledo museum, purchased what he thought was a Hals and gave it to the museum in 1925. By the 1950s, experts studying it decided it didn’t have Hals’ skilled, feathery touch, said Larry Nichols, the William Hutton senior curator of European and American painting and sculpture before 1900. A top-notch Hals portrait was added to the museum’s “must-have” list.

In July, 2010, Mr. Nichols was in a London gallery, meeting with a colleague from the Royal Academy of Arts, with which the museum is planning a joint exhibit of the works of Edouard Manet for October, 2012. In the room was the Family Portrait in a Landscape in a simple frame. For generations, it had been owned by a British family who had loaned it to the National Gallery of Wales 40 years ago. Now it was for sale.

Recognizing it, Mr. Nichols was stunned.

In its original form, ‘Family Portrait in a Landscape’ was much larger than its current 60-inch by 64-inch canvas and featured three more children and a goat. At some point, the painting was divided, and the second portion, at right, known as ‘Three Children with a Goat Cart,’ is now owned by a museum in Brussels.

Later, he walked around London, elated, and mulling what he knew about Hals. The museum was between directors at that time, but Mr. Nichols knew Mr. Kennedy had accepted the job. He contacted him, writing “opportunity knocks,” and Mr. Kennedy encouraged him to open the door.

The London dealer had offered the painting to British and European museums, including one in Brussels that owns a portion of the original owned by Toledo.

When it was painted, the family portrait had been much larger and featured three additional children off to the right. At some point, the canvas was sliced in two unequal parts, perhaps because its owner at the time lacked sufficient wall space, Mr. Nichols theorized: that smaller portion is known as Three Children and a Goat Cart.

Another interesting note: the baby and basket of apples in the bottom left was a later addition, probably because the child hadn’t been born when the rest of the family had posed for Hals. For some unknown reason, the little girl was painted not by Hals but by Salomon de Bray, who signed her shoe and dated it 1628.

It’s easy to see that the baby, with an older-than appropriate face that has more light on it than the others, was done by a less skilled hand. It’s also more colorful and full of lace, perhaps an attempt to out-do Hals.

“It’s harsher,” Mr. Nichols said.

Returning from London, he researched the painting’s importance among Hals prolific body of work, and its value. In March, the portrait arrived in Toledo for additional review.

Conservators examined it and, most important, funds were identified to buy it. Mr. Nichols assembled a dossier justifying the purchase for the museum board’s art committee, which gave the go ahead.

The painting returned to London, and in July, was released for export. Mr. Nichols also supervised construction of a handsome period frame, constructed in London.

Contact Tahree Lane at: 419-724-6075, or tlane@theblade.com.