Detroit’s fiscal crisis imperils art treasures

Museum collection could become bargaining chip

6/2/2013

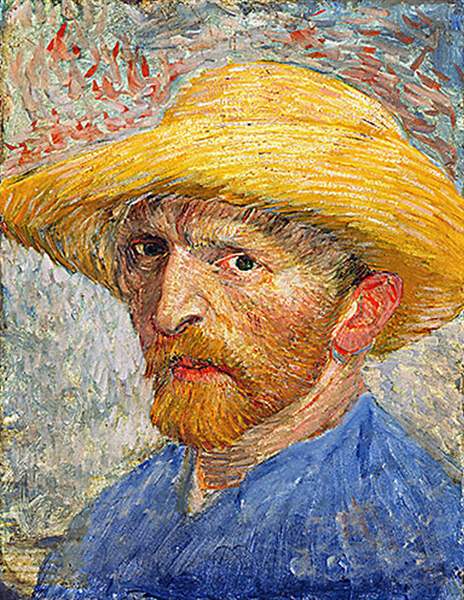

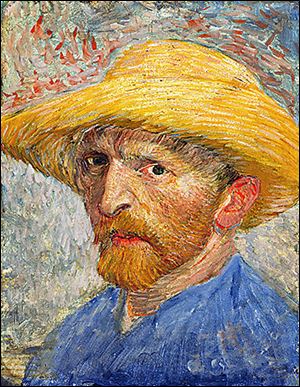

This Vincent van Gogh self portrait at the DIA was the first van Gogh painting to enter a U.S. public collection.

DETROIT INSTITUTE OF ARTS

This Vincent van Gogh self portrait at the DIA was the first van Gogh painting to enter a U.S. public collection.

DETROIT — Is Claude Monet’s serene garden painting Gladioli, or Auguste Rodin’s noble sculpture The Thinker a suitable exchange for paying down a portion of Detroit’s $15.6 billion debt? Are the joyful The Wedding Dance by Pieter Bruegel the Elder or Fra Angelico’s glorious Annunciatory Angel fair trade to satisfy angry bond holders and bond insurers or anxious city employees and retirees?

Art lovers across the country are astonished and outraged that the 60,000 items held for the public by the Detroit Institute of Arts are considered assets by the city’s emergency manager as he does what he’s charged to do: consider all assets and options, negotiate a deal with creditors and stakeholders, and resolve the devastated city’s crushing debt.

Emergency manager Kevyn Orr and Michigan Gov. Rick Snyder, who appointed him, have said they don’t wish to plunder the museum’s billion-dollar vaults, but all city property must be identified for the people to whom the city is in debt.

“Things that are good for the people of Detroit, like Belle Isle and the DIA, are important to the livelihood of the city,” Governor Snyder said Wednesday.

Mr. Orr’s broad powers, outlined in state law, allow him to negotiate with creditors and unions and to terminate contracts, including those with city employees. In the works is his restructuring plan, expected to be completed and presented to the city’s nearly 100 creditors and stakeholders in about three weeks, said Bill Nowling, spokesman for the emergency manager’s office.

The 60,000 items held for the public by the Detroit Institute of Arts — including an 1887 self-portrait of Vincent van Gogh, top right, and Auguste Rodin’s ‘The Thinker’ — are being regarded as assets by the city’s emergency manager as he works to resolve Detroit’s crushing debt.

That’s when talks will start in earnest. If all creditors agree to the plan, details will be hammered out. If not, Mr. Orr can recommend and the governor can approve Detroit’s move into Chapter 9 bankruptcy, which could put the DIA collection at risk.

“We don’t have any plans on the table to sell anything, but we have to have a clear understanding of all the city’s assets and how they provide value to the city,” said Mr. Nowling, adding that both long and short-term values are being considered.

Major assets fall into about 15 categories, of which the DIA is one, Mr. Nowling said. Others include Belle Isle (a 982-acre island park in the Detroit River), the Detroit Zoo, electrical grids, 100,000-plus vacant properties, various buildings, Detroit City Airport, and the Detroit Water and Sewerage Department, which, he noted, provides a regional service, deriving 80 percent of its revenue from outside the city.

Treasures of the DIA

The Wedding Dance, Pieter Bruegel the Elder, ca. 1566.

Sakyamuni Emerging from the Mountains, Chinese, late 13th/early 14th century.

Violinist and Young Woman, Edgar Degas, ca. 1871.

The Last Supper, Jean-Baptiste de Champaigne, ca. 1678.

Bowl, Yankton Sioux culture (Native American), ca. 1850.

The Visitation, Rembrandt Harmensz van Rijn, 1640.

Annunciatory Angel, Fra Angelico, ca. 1450/1455.

Stool — Songye culture, Zaire, 19th/20th century.

Self Portrait, Vincent van Gogh.

Portrait of Postman Roulin, Vincent van Gogh, 1888.

Gladioli, Claude Monet, ca. 1876.

Reclining Figure, Henry Moore, 1939.

Detroit Industry, frescoes, Diego Rivera.

Man Crossing a Square on a Sunny Morning, Alberto Giacometti, 1950.

The Window, Henri Matisse, 1916.

Bather by the Sea, Pablo Picasso, 1939.

Egyptian Mummy, 30 B.C.-395 A.D. Roman Period.

The Thinker, Auguste Rodin.

Young Woman and Her Suitors, Alexander Calder sculpture, 1970.

Winter Landscape in Moonlight, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner.

Mr. Orr has requested a copy of the museum’s entire inventory, the vast majority of which is owned by the city.

“This is completely unprecedented. We just don’t know how this is going to play out,” said Annmarie Erickson, DIA vice president and chief operating officer. “The museum will not sell art unless compelled to do so.” That specter was mere cocktail-party conversation a year ago, she said. “When the emergency manager was appointed, that’s when we knew we were in a different situation.”

‘A travesty’

What’s unique about Detroit’s museum, considered to have one of the best art collections in the country, is that not only its buildings but its collection have been owned by the city for almost 100 years, although city dollars for the DIA have been scant to none recently.

The art world’s reaction can be summed up in five words: “I think it’s a travesty,” said Jackie Nathan, gallery director at Bowling Green State University. “I hope they back away from this because it’s not a sound decision to dispose of your treasures in time of difficulty.”

If Mr. Orr and Mr. Snyder decide the best road to resolution is through bankruptcy, creditors, who will certainly take a hit, and the judge could pressure the city into selling real estate, buildings, systems, and even inspired artifacts that are rare and ancient.

The DIA’s Ms. Erickson and others intone a single phrase: It’s uncharted territory that’s legally complicated and untested.

But it couldn’t happen here. Even if the city of Toledo went belly-up, the Toledo Museum of Art would not be touched because it is a private nonprofit and owns its art, buildings, and property.

Of particular irony is that Detroit-area voters in Wayne, Oakland, and Macomb counties endorsed the museum on Woodward Avenue in August when they approved a levy that will raise an estimated $23 million a year for 10 years, putting it on sound financial footing for the first time in decades. But even that life support could be jeopardized if art is sold to pay debt.

“If this happens, our millage would be voided,” said Pamela Marcil, DIA public relations manager. “The agreement says we have to operate according to professional museum standards.”

Emergency manager Kevyn Orr, left, and Michigan Gov. Rick Snyder have said they don’t want to plunder the museum’s vaults, but all city property must be identified for the people to whom the city is in debt.

‘The public trust’

Museum holdings are not considered collateral, even for tax purposes, said Dewey Blanton, director of strategic communications at the American Alliance of Museums in Washington.

Museums that receive accreditation by their industry’s organizations must meet certain criteria, and selling a collection to pay debt violates the standards of the American Alliance of Museums, by which the DIA and 1,000 museums from art to zoos, are accredited. It is a museum’s promise to keep and care for its goods for the people that makes them different from an individual or corporation that can own and sell its art at will.

“Museums hold their collections in the public trust, not for private gain or to fix the boiler. That’s their obligation,” Mr. Blanton said. “The potential to have to sell something to balance a city’s books is something we’ve never come across.”

Museums sell objects for various reasons; perhaps the item is seldom on view or is part of a particular style of art the museum has plenty of. Proceeds from sales must be used to buy additional art or to care for the collection, not to pay down debt, according to accreditation standards.

In a gesture of support and an attempt to protect the DIA, a bill was introduced Wednesday in the Michigan Senate requiring the state’s art museums to subscribe to accreditation standards.

A quick estimate of the market value of 38 of the DIA’s greatest masterpieces by art dealers was at least $2.5 billion, according to an article in the Detroit Free Press, including paintings such as Bruegel’s The Wedding Dance, van Gogh’s Self-Portrait, and Matisse’s The Window judged to be worth between $100 and $150 million each.

History of DIA

Among the Detroit Institute of Arts’ many notable works is ‘Gladioli,’ 1876, by the Impressionist Claude Monet.

Most museums, such as Toledo’s, are nonprofits governed by a board, Mr. Blanton said, and they may receive some tax dollars.

Detroit’s museum was founded in 1885 as a private nonprofit by wealthy residents, who soon turned to the city for support, which the growing city provided. It was the Progressive Era, when a popular belief held that government could and should improve people’s lives, said Jeffrey Abt, author of A Museum on the Verge: A Socio-Economic History of the Detroit Institute of Arts from 1882 to 2000.

In 1919, the founders asked and city fathers agreed to assume control of the building and collection, running it as a municipal department, opening its majestic Woodward Avenue Beaux-Arts building in 1927 2 miles north of downtown, and buying art when the city was flush.

By the mid-1950s, Detroit’s population began declining and, consequently, city revenues began the shrinking. That has continued steadily for nearly 60 years. In 1975, the DIA was forced to close for a short time, but the state of Michigan stepped in to keep the doors open, said Mr. Abt, a professor of art history and art at Wayne State University.

Eventually, the city subcontracted museum operations to the nonprofit DIA’s Founders’ Society. Bond issues by the state and city helped the museum complete a beautiful $158 million renovation and expansion in 2007.

For a museum that began as Eurocentric, the DIA has particular diversity as a result of significant holdings in African, Asian, Native American, Oceanic, Islamic, and ancient art. In 2000, it established the General Motors Center for African American Art.

‘The Wedding Dance,’ by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, 1566, is among the works on display at the Detroit museum.

For the time being, museums and art groups, as well as municipal leaders across the nation, are watching with fascination as Detroit’s financial fix unfolds.

“We’re keeping a very close eye on the situation,” said Christine Anagnos, executive director of the 226-member Association of Art Museum Directors. “Ultimately, museums are stewards when you come right down to it.”

And a grass-roots effort has sprouted.

Taking action

Sean Warren of Novi, a Detroit suburb, started an online petition through MoveOn.org that includes this: “Do not sell DIA assets; the toll could be monumental, permanently diminishing a museum widely recognized as one of the country’s best.”

Mr. Warren said he wanted to do more than discuss the issue on Facebook, and a friend suggested they organize something. As of Friday afternoon, the petition had nearly 600 signatures. “We’re thinking about a rally in front of the museum to deliver the petitions once we get about 5,000 signatures,” said Mr. Warren, a project manager for an advertising firm.

He hasn’t been much of an art fan, but last year his aunt gave him free passes to the DIA and he went, finding the atmosphere stimulating enough to propose to his girlfriend, now his fiancee.

Contact Tahree Lane at: tlane@theblade.com and 419-724-6075.