Byrds' pioneering country rock experiment changed America's musical landscape for good

9/21/2003

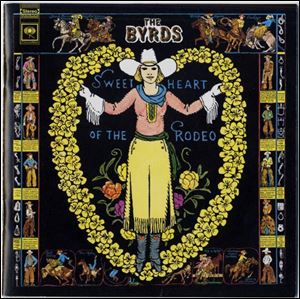

The Byrds' re-release of 'Sweetheart of the Rodeo'

The very first sound on the Byrds' seminal “Sweetheart of the Rodeo” is pedal steel guitarist Lloyd Green peeling off a twang-heavy lead, sending a bracing signal that the pre-eminent California pop/rock band of the '60s had gone Nashville.

The record, a stone-cold country release from its opening track to the last, caused an uproar in both rock and country circles because one of the biggest rock bands of the time had launched a genre-bending foray into a musical form that was considered conservative, and worst, hopelessly square.

Rockers felt like their band, the guys who crafted the druggy hits “Turn! Turn! Turn!" and “Eight Miles High” - and who turned them on to the psychedelic side of Dylan with their definitive cover of “Mr. Tambourine Man” - had somehow gone over to the dark side.

And the country set was in a tizzy over these dope-smoking long-hairs co-opting their music, singing the traditionalist songs of Merle Haggard, the Louvin Brothers, and Woody Guthrie.

Thirty-five years after the album's release, Columbia is revisiting “Sweetheart of the Rodeo” in a two-disc, 39-song package. Included is the original album, outtakes, rehearsals, and six songs from the International Submarine Band, the group Gram Parsons fronted before joining the Byrds.

Billed as a “Legacy Edition,” the re-release begs the question: Is “Sweetheart of the Rodeo” a dated artifact from a different era, or is it a bona fide classic that seeded the fertile stylistic cross-pollination that gave us country rock, folk rock, alt-country, and the massively successful Eagles?

The answer is elusive and it depends a little bit on who's asked.

Chris Hillman, the Byrds bass player, and principle writer along with Parsons and Roger McGuinn, isn't a big fan of the album, damning it with the faint praise of being an “interesting record.”

In John Einarson's 2001 definitive history of the California folk rock movement, Desperados. The Roots of Country Rock,” he says the vocals by McGuinn and Parsons are a bit phony because they lacked the conviction necessary to pull off something like Merle Haggard's “Life in Prison” or the Louvin Brothers ode to clean living, “The Christian Life.”

Parsons was a rich, Harvard-educated guy who never spent time in prison, and McGuinn sings “The Christian Life” in a faux southern accent, apparently because he didn't much believe in what he was singing, notes Hillman, who is equally hard on himself.

“Roger is definitely putting on an affected southern accent on that album” he says in Einarson's book. “I think he approached it like an acting job, although not a good acting job. But I couldn't sing at the time because I didn't have the chops developed as a singer. So Roger was the guy to sing them. It's funny, it's silly.”

But McGuinn, the creative center of the band, praises the record and is outspokenly satisfied with it, no matter how much it might have alienated their rock fans and the country establishment.

“We were trying to record an authentic country album,” he told Einarson. “I'm very proud of `Sweetheart' now.”

Others, especially music critics, cite the album as a huge influence on countless artists. They rate “Sweetheart of the Rodeo” as the definitive country rock record, the first time hard-core rockers crossed over completely, paving the way for countless other acts.

Which is something of an overstatement in one regard: at the same time the Byrds were experimenting with country and bluegrass music, so were Neil Young and Steven Stills (in Buffalo Springfield), Bob Dylan, the Band, the Grateful Dead, the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band, the early versions of Poco, and Parsons in the International Submarine Band.

So while the Byrds may not have been the first, they most definitely were the biggest act at the time to engage in such experimentation. They beat Dylan to the punch - his “Nashville Sklyine” came out a year later - and Young and Stills weren't yet the stars they would become.

More than anything the album proved that a band can evolve aggressively beyond the stylistic niches ascribed to them by critics and fans, pursuing their own interests in a manner that ultimately is more rewarding than churning out assembly-line music.

And it has some great tunes.

The entire album of 11 songs is rustic and timeless, filled with the incongruities and contradictions that make country music the white man's blues. There are songs about boozing, Jesus, broken hearts, longing, and living the simple life, and each one features the perfect harmonies of Hillman, Parsons, and McGuinn.

Unfortunately, this incarnation of the Byrds - always a revolving-door band - didn't last long after the release of “Sweetheart”. Parsons, a notorious partier who died of a drug overdose in 1973, bailed out shortly after it was released and he and Hillman went on to form the Flying Burrito Brothers.

McGuinn and drummer Kevin Kelly hung in there as the Byrds for several years, but never met with much popular acclaim and didn't record anything that matched the inspiration and artfulness of “Sweetheart.”

Over the years, the album - never a big seller - took on a greater contextual weight as more bands used it as a template for their sound and their creative experiments. At the time, “We weren't sure we could keep our rock and roll audience and we weren't sure if we could gain a country audience,” said McGuinn.

But time has shown that the Byrds made it cool, and safe, for groups like the Jayhawks, Wilco, Uncle Tupelo, Lucinda Williams, John Hiatt, the Eagles, and countless others to mix country and rock without fear of losing their fan base.

For that, “Sweetheart” is truly a landmark album.