'Tatum's Town' highlights Toledo's long love affair with music

12/22/2017

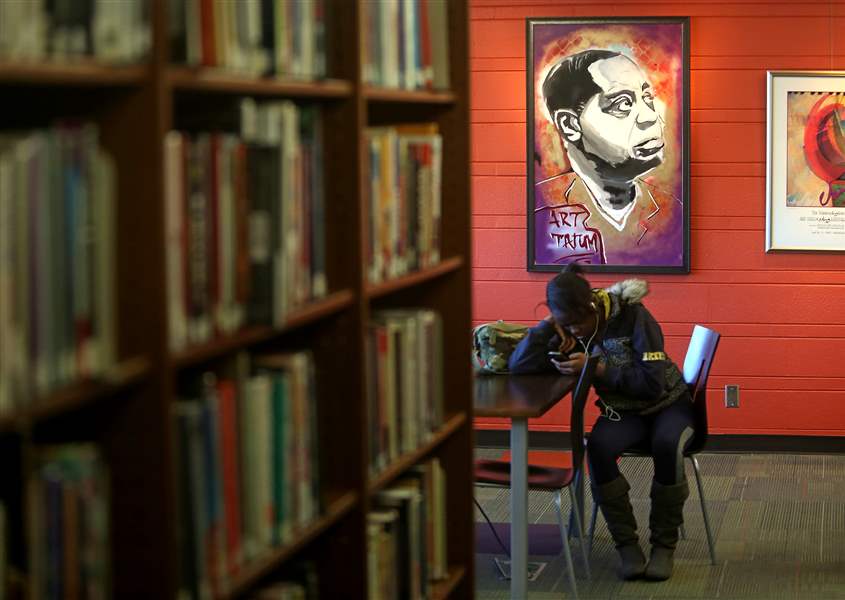

Taylor Lewis, of Toledo, relaxes on her phone, at the Art Tatum African American Resource Center at the Kent Branch Library in Toledo on Friday, December 8.

The Blade/Kurt Steiss

Buy This Image

When jazz icon Jon Hendricks died a month ago, his global impact on the music industry became all the more evident by the thousands of stories about his passing carried in publications across North America and as far away as Russia, Japan, France, Great Britain, Australia, and India.

Social media was abuzz. People learned more about Hendricks’ amazing life and his storied career. They also, to some degree, had their appetites whetted about the hardscrabble, working-class northwest Ohio city where Hendricks grew up — a place better known to many parts of the world for producing Jeeps than jazz.

Taylor Lewis, of Toledo, relaxes on her phone, at the Art Tatum African American Resource Center at the Kent Branch Library in Toledo on Friday, December 8.

But as many people in America’s heartland know, Toledo has had a decades-old love affair with jazz. It’s a theme explored with mixed results in a little-known book released earlier this year called Tatum’s Town: The Story of Jazz in Toledo, Ohio (1915-1985).

Seventy of the city’s most formative years of jazz are covered.

While this book is a self-published effort that suffers from some organizational flaws, it is rich with historical anecdotes about Toledo’s connection to anything from Dixieland to bebop and swing.

It offers a precious collection of photographs and images of memorabilia to go with what author Bob Dietsche describes as a “labor of love” that included more than 30 years of research.

Dietsche is a 1955 DeVilbiss High School graduate and jazz aficionado who lived in Toledo between from age 5 to 19. He left Toledo for the West Coast more than 60 years ago and graduated from the University of Oregon in 1961 before settling in Portland, Ore.

VIDEO: Art Tatum, Tiger Rag

He has taught English and composition in high school and college and jazz history at community colleges. He has written several jazz articles and hosted jazz radio shows, including Jazzville on Oregon Public Broadcasting.

Dietsche also owned and operated a used record store, Django Record Co., from 1977 to 1999 and is author of a book similar to the one he wrote about Toledo, Jump Town: The Golden Years of Portland Jazz, 1942-1957.

Brett Collins, a librarian specialist with the Toledo-Lucas County Public Library, speaks during an interview at the Art Tatum African American Resource Center at the Kent Branch Library in Toledo on Friday, December 8.

Toledo and Portland have something in common, music-wise, in that both are inland sea ports with great railroads and great jazz, according to Dietsche.

The only Toledo-raised jazz musician with more name recognition than Hendricks is pianist Art Tatum, who was born Oct. 13, 1909, on Mill Street in Toledo’s South End.

Tatum had a fiery-yet-graceful style that still influences musicians today.

As jazz giant Billy Taylor once wrote, Tatum “was unquestionably the quintessential jazz pianist.”

Tatum ultimately became a guiding force for Hendricks, who credits Tatum with giving him the confidence he needed to succeed in 1935 when he was 14 years old and singing with the world-famous pianist he held in awe.

“I learned everything from him,” Hendricks said of Tatum in a 1986 interview.

But who else comes to mind as Toledo jazz legends other than Tatum and Hendricks?

In Tatum’s Town, Dietsche makes a case for anyone from big band jazz orchestra leaders Johnny Knorr (whom he describes as the “Glenn Miller of the Midwest”) and Sam Szor to saxophonist Jerry Sawicki.

But there are many others: Dietsche also offers vignettes of trumpeter Jimmy Cook; saxophonist Gene Parker; bassist Clifford Murphy and his longtime sidekick, pianist Claude Black; pianist Eddie Abrams; clarinetist Ray Heitger; pianist El Myers; pianist Johnny O’Neal, and many, many others.

Paintings and posters on display at the Art Tatum African American Resource Center at the Kent Branch Library in Toledo on Friday, December 8.

He describes Arv Garrison as a flash-in-the-pan who seemed destined for a career as one of the world’s greatest guitarists before flaming out. Garrison was, according to Dietsche, the “most highly acclaimed guitarist to come out of Toledo.”

Garrison, who battled epilepsy much of his life, played alongside legendary saxophonist and bebop innovator Charlie Parker on some of his most historic recordings. He also appeared on the cover of DownBeat magazine in 1946, which back then — as Dietsche noted — was an especially big deal. But Garrison’s talent somehow slipped away. Even though he was a great swimmer, he drowned in a swimming accident at Centennial Terrace on July 30, 1960.

Dietsche is especially fond of African-American trombonist Jimmy Harrison, who only lived to be 31 but was known as the “Toledo Terror” for how he, according to Dietsche, adopted the trumpet style of Louis Armstrong to his trombone.

“Even in a field crowded with forgotten giants, Harrison stands out as one of the most-neglected figures in all of jazz, perhaps the most important jazz musician not in the Hall of Fame,” Dietsche wrote.

The author contends that Toledo’s connection to jazz got a huge boost on July 4, 1919, when the city hosted a much-anticipated fight between heavyweight champion Jess Willard and challenger Jack Dempsey.

The event lasted only three rounds. But, for a brief time, it made Toledo the epicenter of the sporting world, drawing tens of thousands of people into the city for the event. That, in turn, drew strippers, dancers, ragtime pianists, jazz musicians, singers, and others to entertain them. Some — such as Harrison, pianist Elise Young, and drummer Velmar “Fats” Mason — ended up staying in Toledo, according to Dietsche.

“Willard was no match for Dempsey’s youth and speed. It was one of the worst beatings ever in the history of boxing. Willard’s face looked like a piece of raw beefsteak,” Dietsche wrote, adding that the city also reached a blistering 104 degrees that day.

But, he argues, the Willard-Dempsey fight solidified Toledo’s reputation as a place for jazz.

Bob Dietsche, author of "Tatum’s Town: The Story of Jazz in Toledo, Ohio (1915-1985)."

Dietsche offers glimpses of classic venues from yesteryear throughout his book, such as Chicken Charlie’s on Lafayette Street, Chateau de la France along Dorr Street, and the Waiters and Bellman’s Club on Indiana Avenue.

He writes about Centennial Terrace in its heyday as well as businesses such as Seligman’s Record Bar, which he claims was once one of America’s best record stores.

Dietsche writes lovingly about the late Rusty Monroe, owner of the iconic Rusty’s Jazz Cafe on Tedrow Road in South Toledo, which for decades featured live jazz nightly and gained an international following.

He also gives a surprisingly brief nod — a chapter that’s less than two pages — to the Cakewalkin’ Jass Band, which earlier this month celebrated its 50th anniversary with a trio of standing-room-only performances at the Original Tony Packo’s restaurant in East Toledo. Cakewalkin’, described in the book as Toledo’s “most enduring” jazz group, spent all but 18 months as the house band at that restaurant from 1968 to 2001.

“I had no idea Toledo had so many jazz luminaries,” Dietsche told The Blade.

He said he got the idea for the book after reconnecting with DeVilbiss friends and realizing his passion for jazz gave him an excuse for multiple returns to his hometown.

He said he made more than 36 trips from Portland to Toledo and back over 30 years for research and interviews.

“It was my way of going home again,” Dietsche said. “I combined business with pleasure.”

Much of what’s in Dietsche’s book has its rightful place in Toledo’s jazz legacy.

But for many musicologists, Tatum and Hendricks will always be the first two names that come to mind when the subject of jazz comes up.

Brett Collins, son of jazz vocalist Ramona Collins, calls Tatum and Hendricks “the most incredible ambassadors you could have.”

A former journalist, Collins has been a librarian specialist for the Toledo Lucas County Library since 2010 and oversees the Art Tatum African American Resource Center that was created in 1989. It is housed at the Kent Branch Library, 3101 Collingwood Blvd., in Toledo’s Old West End.

Tatum died 61 years ago, back in 1956. But people haven’t forgotten him. Six decades from now, it’s unlikely they will have forgotten Hendricks, either.

“The history [those two] have is Toledo history. With Tatum in particular, it’s world history,” Collins said. “It’s important to keep his name alive and on the jazz scene.”

Toledo is, after all, Tatum’s Town.

Contact Tom Henry at thenry@theblade.com, 419-724-6079, or via Twitter @ecowriterohio.