Toledo was hub of interurban 100 years ago

5/27/2007

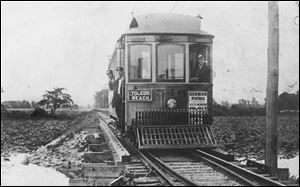

Interurban railways like the Toledo Beach line, above, helped expand travel between cities. By 1908, Ohio had 2,800 miles of interurban routes, 1,000 miles more than in any other state.

As the 19th century drew to a close, travel between cities or from farm to market was a tedious affair.

Usually it involved a bumpy wagon ride on rutted roads, which could be made impassable by mud or snow.

While electric streetcars served city dwellers and steam railroads crisscrossed the nation, passenger service to many smaller communities was relatively infrequent, expensive, and often not tailored for short-distance day trips.

But the perfection of systems that could distribute electricity over long distances was changing that. Power companies looked at the trolley networks that provided cheap mass transportation in many major cities and took what looked like the next logical step: Why not run electric-powered railways out into the country, or even link cities? Doing so would provide for transportation needs and create new markets for electricity service.

Thus the interurban railway was born, and nowhere was it more prevalent than in Ohio. Accounts differ as to which was first, but one of the earliest lines was a route that opened in 1893 between Sandusky and Norwalk. As the century turned, interurban railways sprang up all over the Midwest. By 1908, the 2,800 miles of interurban routes in Ohio were 1,000 miles more than in any other state.

Flat terrain and relatively dense population, with small agricultural communities scattered throughout, had made Ohio and its neighboring states ideal places to build interurban railways. And for a short time, interurban railways were the fifth-largest industry in the United States.

Toledo, which quickly developed into a major hub, was served by 11 interurban companies. Frequent service was available to Monroe, Blissfield, Metamora, Wauseon, Waterville, Bowling Green, Fostoria, Oak Harbor, Genoa, and other nearby towns.

Hourly or every-two-hours service was available to more distant cities like Cleveland, Detroit, Dayton, Cincinnati, and Fort Wayne. Even Put-in-Bay had a line - a mere 1.5 miles long, with eight trolley cars.

Local service was the interurbans' forte; the Toledo & Indiana route, as an example, had 31 stations on its 57-mile route between Toledo and Bryan.

For many years, the Cincinnati & Lake Erie's 217-mile Toledo-Cincinnati run was the longest direct trolley in the United States. But by changing from one line to another, it was possible to travel even greater distances. One could travel by interurban all the way from the upstate New York city of Oneonta to Elkhart Lake, Wis., north of Milwaukee.

The interurbans' big electric rail cars dwarfed the city trolleys whose tracks they shared while running in and out of the downtowns. Out on open track in the countryside, they routinely galloped along at up to 80 mph. Electric propulsion permitted rapid acceleration and inexpensive operation, so the interurbans could make frequent stops and offer lower fares than had been possible on traditional railroads.

Interurbans were a hit with traveling salesmen, who suddenly had a convenient way to hop from town to town. They allowed scholastic sports teams to travel farther for competition. Farmers could ship produce conveniently to nearby markets in a matter of hours, while newspapers, machine parts, and other goods could be delivered quickly from city suppliers to rural customers. People of modest means could afford to travel to cities for cultural events or to outlying recreational and resort sites such as Lakeside and Cedar Point. And interurban trains permitted out-of-town commuting on a large scale for the first time.

As rapid was their rise, so too did the interurban railways' fortunes fall.

Even as trolley tracks spiderwebbed across the Midwest's vast farm fields, the technology that would supplant them was being perfected: the automobile.

Early autos were too expensive for all but the wealthy to afford and too fragile to use on rough rural roads. But Henry Ford's development of the Model T assembly line in 1908 and the spread of roadway paving thereafter soon made automobile travel much more practical.

As the nation boomed during the 1920s, the interurban rails suffered as travelers began forsaking them for the independence of the private car.

By 1939, the interurban era in Toledo was dead. That was the year the last Toledo & Indiana car arrived at the Vulcan station, near the University of Toledo, and the last TPC&L service to the downtown interurban station at Jackson and Superior streets ceased.

In northwest Ohio and southeast Michigan, only traces remain from the heyday of electric rails.

The University/Parks trail, which runs from the University of Toledo to Secor Metropark, follows the old Toledo & Western right-of-way. The odd angles that Clarion Avenue and Dulton Drive cut across Holland and western Toledo, and the high-tension line that follows those streets, are remnants of the old T&I. And the wide right-of-way along Tremainsville Road dates back to when that thoroughfare was paralleled by an interurban.

Bits of right-of-way can be spotted elsewhere in the region. Perhaps the most prominent relic of the interurbans' past is the abandoned Cincinnati & Lake Erie concrete-arch bridge across the Maumee River west of Waterville - commonly known as "the Old Streetcar Bridge."