COMMENTARY

A New Year’s resolution for second chances

Any society willing to throw away the key on a 14-year-old has lost all faith in redemption and people’s ability to change

1/5/2014

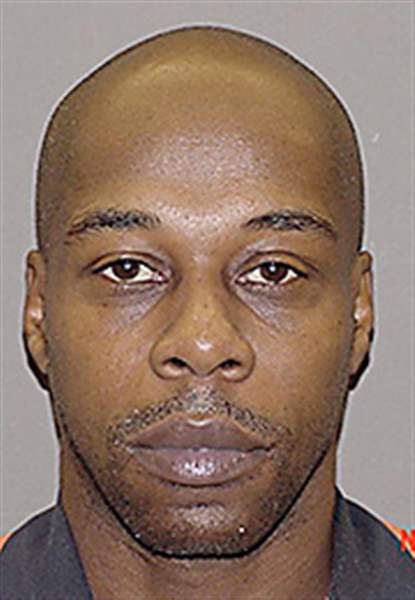

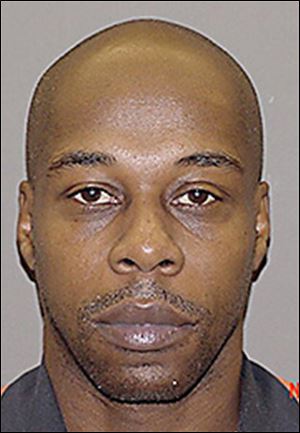

Hill

HANDOUT NOT BLADE PHOTO

Jeff Gerritt

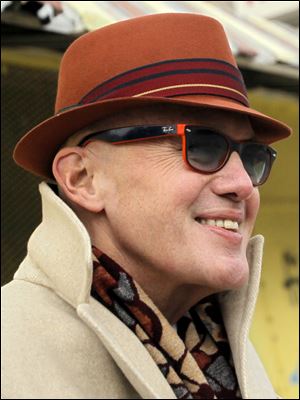

Every journalist undertakes a few crusades and lost causes. One of mine has been trying to persuade Michigan authorities to scrap the state’s barbaric juvenile lifer law, which Michigan’s bloodless attorney general, Bill Schuette, continues to defend.

Enacted along with other Draconian sentences in the 1980s, Michigan’s law imposed mandatory life sentences — the maximum adult penalty in that state — on hundreds of teenagers, some as young as 14. Any state, or society, that’s willing to throw away the key on a 14-year-old has lost all faith in redemption, and in people’s ability to change.

The law defied science, public opinion, and common sense. Kids don’t have the same legal rights and responsibilities as adults because they lack the maturity and judgment to handle them. But Michigan’s juvenile lifer law imposed the same standards of accountability on children too young to drive legally or smoke cigarettes as it did on adults.

Appealing to the conscience of state lawmakers, I wrote more than 50 editorials and columns at the Detroit Free Press from 2000 to 2012 that attacked the juvenile lifer law. I would have had better luck appealing to the conscience of a crack dealer.

Schuette

Politicians run like scared rabbits from the soft-on-crime label, even if what they’re running from makes perfect sense. Bills introduced in the Legislature to repeal the juvenile lifer law rarely got out of committee.

Hill

Last year, the U.S. Supreme Court finally did what Michigan’s spineless legislators and governors had refused to do: strike down the mandatory sentencing of juveniles to life in prison without parole. The high court said the law violated the Eighth Amendment’s ban on cruel and unusual punishment.

Not surprisingly, Mr. Schuette fought the ruling, arguing that it should not apply to past cases. That would make almost all of the more than 350 juvenile lifers now locked up in Michigan ineligible for parole. Nationwide, there are 2,500 such cases.

A month ago, while I was driving to Columbus, I got a call from Henry Hill, a 50-year-old prisoner at Thumb Correctional Facility in Lapeer, Mich. A lead defendant in the federal juvenile lifer lawsuit, Hill was one of the many juvenile lifers I profiled. Over the years, he became not only a source but also a friend.

“Have you heard the news?” he said. “[U.S. District] Judge John O’Meara just ordered Michigan to start holding parole hearings for all the juvenile lifers.”

It was one of those moments when I felt good about how I make a living. We all want to make a difference. Maybe, after all, I had.

Fed up with the state’s recalcitrance, Judge O’Meara ordered Michigan to create an administrative structure to determine which juvenile lifers deserve parole, notify juvenile lifers who had been locked up for at least 10 years that they will be considered for parole, and schedule public hearings for eligible prisoners. He also ordered the state to make the same education and training programs available to juvenile lifers that it offers to the general prison population.

This order would not open the prison gates. In fact, granting juvenile lifers parole hearings would not, in itself, release a single offender. Members of the state parole board still could deny parole if they determine that a person poses a threat to society.

Still, many juvenile lifers ought to be released. Dozens have served decades in prison — where they each cost taxpayers $35,000 a year — and long ago turned their lives around.

No doubt, they were involved in serious crimes. Michigan’s juvenile lifer law applies only to first-degree murder. Under Michigan law, however, aiding and abetting a first-degree murder carries the same penalty.

Many juvenile lifers were marginally involved with the crimes they were convicted of. Nearly half were convicted of aiding and abetting. Hill, who grew up in Saginaw, was one of them.

Witnesses, including an off-duty sheriff’s deputy, testified that Hill, then 16, was running from the scene when his cousin, Larnell Johnson, shot and killed Anthony Thomas during a fight at a Saginaw park in the summer of 1980. Before Hill left, he fired several shots into the air, trying to scare people away. None of Hill’s bullets matched those found in the victim’s body, but he received the same sentence as his 18-year-old cousin: mandatory life.

In a court-ordered evaluation, a psychologist called the 16-year-old Hill mentally deficient, insecure, and unable to tell right from wrong. The report states that Hill had the education level of a third-grader and the mental maturity of a 9-year-old. In no way should he have been judged by adult standards.

“I was dumb as a box of rocks,” Hill once told me during a prison interview. “I couldn’t even read. I was 20 before I really realized the significance of what I had done.”

Hill no longer — physically, mentally, or emotionally — resembles the teenager who entered prison more than 30 years ago. He is bright, articulate, and well-read. He earned a GED in prison and took college courses. Hill married Valerie, a longtime supporter, and has found a profound faith in God.

A recent psychological evaluation completed by the Michigan Department of Corrections called Hill cooperative, polite, articulate, and straightforward. It concluded that his thinking is logical, flexible, and goal-oriented.

Although he didn’t kill anyone, he feels remorse for his part in a crime that took another’s life. He knows he deserved to be punished. But after more than 30 years in prison, it’s long past time to give Hill and others like him a chance to move past the mistakes they made as immature teenagers.

When is enough enough? Never, according to Mr. Schuette. Last month, the attorney general appealed the ruling. Two days before Christmas, the 6th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in Cincinnati stayed Judge O’Meara’s order.

We’ve just finished a holiday that celebrates redemption and forgiveness. These virtues rarely apply to criminal justice — certainly not to Michigan’s juvenile lifer law or the state’s ambitious attorney general.

The ability to change is part of what makes us human. When we lose faith in that, we become something less.

Jeff Gerritt is deputy editorial page editor of The Blade.

Contact him at: jgerritt@theblade.com, 419-724-6467, or follow him on Twitter @jeffgerritt.