BLADE INVESTIGATION

Lax oversight jeopardizes tax credit projects

Toledo low-income homes fall short of inspection guide

6/25/2012

Second in a series.

A recently built house on Avondale Avenue is vacant and boarded up, in contrast to nearby older structures, which are occupied.

The Ohio Housing Finance Agency is supposed to inspect tax credit projects at least once every three years.

In reality, it does so far less often, sometimes visiting projects only once every six years.

A Blade investigation of roughly 800 low-income tax credit homes in Toledo has revealed deep flaws in the state agency's oversight of the program -- flaws that likely contributed to what has become a desperate situation in the city's poorest neighborhoods. There, more than 100 houses constructed or renovated with millions of dollars in taxpayer money are now boarded up, gutted, or burned out, contributing to years of decline rather than the housing renewal that was hoped for and promised by city officials.

RELATED ARTICLE:Taxpayer-aided homes sit vacant, vandalized

The complicated nature of the program has also produced a system in which the beneficiaries of the tax credits -- primarily large corporations such as banks, insurance companies, and tech firms -- receive tax breaks even as the low-income rental homes for which they received the credits fall apart.

Top officials of the Ohio Housing Finance Agency in Columbus, which is charged with administering the program, blamed the lack of regular inspections on Tom Evans, its sole employee in Toledo.

He was fired in May, shortly after The Blade began requesting documents from the agency.

"The problems encountered in the Toledo outstation are an unfortunate exception," said Arlyne Alston, a spokesman for the agency.

Records show Mr. Evans, who became the agency's Toledo-area housing examiner in 2004 and was paid a yearly salary of $58,427 when he was fired, failed to file more than 70 reports, missed meetings, spent up to an hour each day driving to the post office, and sometimes called in sick without providing a physician's note. He was suspended twice before he was fired.

Attempts to reach Mr. Evans were unsuccessful.

Boarded Tax Credit Properties

But even before 2004, the finance agency failed to conduct regular inspections of projects in Toledo, according to a review of its files.

Toledo Homes I, a 48-house project built in 1997, was visited in 1998, but not again until 2004. The 1998 inspection reveals the importance of monitoring.

Inspectors found dozens of problems, including basement flooding, soft spots in a kitchen floor caused by a leak, and loose wires in a basement.

By 2008, at least 11 units in Toledo Homes I were vacant, according to documents from a bankruptcy case involving one of the project's former property managers. Today, 16 houses -- exactly one-third -- are boarded up. That represents millions of dollars in lost taxpayer investment.

The lack of oversight could also put the finance agency in hot water with the IRS. If a state housing agency fails to meet its compliance monitoring requirements, it can lose its authority to allocate credit.

Douglas Garver, executive director of the finance agency, issued a statement in response to The Blade's investigation:

"I am concerned that the lease purchase properties in Toledo are not performing well and disappointed that OHFA did not consistently inspect the properties in a timely manner," he said. "I am further disappointed that OHFA did not meet my expectations and those of the community in doing what it could do to monitor the performance of the properties and document non-compliance."

He said the agency plans to review all single-family tax-credit homes in Toledo by Aug.21. The agency plans to inspect all other tax-credit projects in Toledo, such as apartment buildings and senior housing facilities, by January, 2013.

"OHFA has an action plan in place to ensure that the agency fulfills its commitment to strong compliance standards and continues to provide affordable housing for Ohioans who need it the most," Mr. Garver said.

About the program

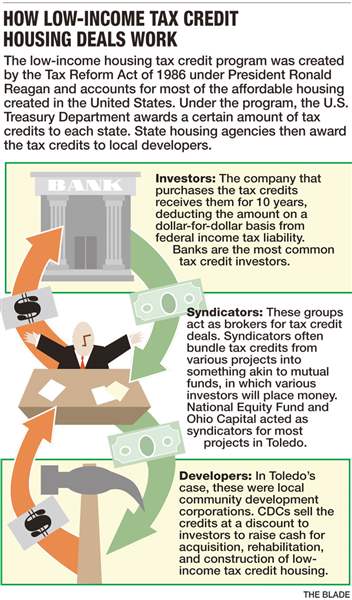

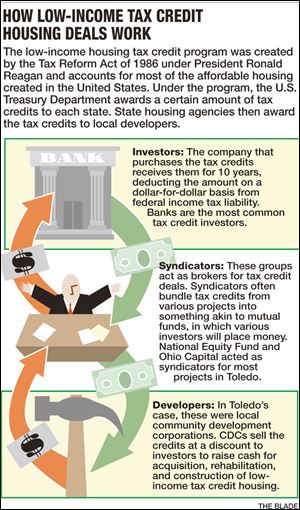

The low-income housing tax credit program was created by the Tax Reform Act of 1986 under President Ronald Reagan and accounts for most of the affordable housing created in the United States.

Under the program, the U.S. Treasury Department awards a certain amount of tax credits to each state. State housing agencies then award the credits to local developers, who sell them at a discount to investors such as banks or insurance companies to raise cash for acquisition, rehabilitation, and construction.

The company that purchases the tax credits receives them for 10 years, subtracting the amount on a dollar-for-dollar basis from their federal income tax bill. In exchange, the owner of the development must maintain income and rent restrictions for 15 years.

The tax-credit program is extremely popular and, as a result, extremely competitive. The Ohio agency funds only 25 to 30 percent of the applications it receives each year.

It currently has 840 active projects and 21 compliance staffers -- 13 of whom conduct site inspections. IRS regulations require the agency to conduct on-site inspections at least once every three years.

During those visits, compliance officers are supposed to review project files to make sure rent limits and tenant income levels are in compliance with requirements.

They are also supposed to physically inspect 20 percent of the housing units and all building exteriors.

Last year, the state finance agency inspected 423 projects, or about 43 percent -- proof that infrequent inspections of Toledo projects are an exception, Ms. Alston said.

She said OHFA reviews annual compliance reports submitted by project owners, though Brian Carnahan, director of program compliance for the finance agency, acknowledged that those reports rely on owners providing accurate information.

"It's a system based on honesty," he said.

If inspectors find that a project is out of compliance, it gives owners a chance to correct the issue. If owners don't, the finance agency can report the project to the IRS, which can recapture tax credits from corporate investors in the project.

Records show that OHFA has occasionally filed noncompliance notices with the IRS, but usually only because a project owner failed to submit paperwork on time. The IRS typically does not tell the state what action, if any, it took, Mr. Carnahan said.

Corporate investment

The dire situation of Toledo's tax credit homes, coupled with the finance agency's lack of oversight, raises questions about whether those corporate investors are receiving tax credits that don't do what they were intended to do.

The IRS requires that tax credit housing units be "suitable for occupancy" for the purpose of calculating tax credits. If a unit becomes uninhabitable during the 15-year compliance period, the IRS can recapture tax credits and impose penalties.

Determining who those corporate investors are is difficult because investments are made through syndicators, which act as brokers for tax-credit deals.

Syndicators often bundle tax credits from various projects into something akin to mutual funds, to which various investors buy in. Banks are the most common tax credit investors because they are familiar with the underwriting for such projects and because the Community Reinvestment Act of 1977 requires them to invest in low-income neighborhoods and avoid discriminatory lending practices.

National Equity Fund and Ohio Capital acted as syndicators for most projects in Toledo. The presidents of both firms declined to name the investors in specific projects.

But finance agency documents show at least some of the investors because their notes were used to secure gap financing loans from the agency. For the Toledo Homes projects, investors included familiar names -- Bank of America and the community development arms of Fifth Third and Huntington banks -- as well as a lesser-known company: Digi International, a Minnesota technology firm.

Recapturing credits

The Blade reached out to syndicators and investors in an attempt to determine whether tax credits were being received for dilapidated and uninhabitable homes.

Jefferson George, a spokesman for Bank of America, said the bank had only a 10 percent share in a fund managed by National Equity Fund. "This essentially makes us two steps removed -- a minor owner and nonmanaging member of a fund that is a limited partner in the real estate," he said. "In this case, we did take recapture in line with our very small ownership."

A recapture occurs when the taxpayer must repay earlier tax savings by paying additional taxes.

Brent Wilder, a vice president with Huntington Bank, said National Equity Fund would be responsible for taking any recapture on a tax credit investment. "We are comfortable that appropriate recapture activity has been taken," he said.

Hal Keller, president of Ohio Capital in Columbus, said no credits have been recaptured for its projects, which include Oakwood Homes IV, a 35-house project with 10 boarded-up houses on and around Oakwood Avenue just east of downtown.

Mr. Keller said the boarded-up units are ready to be rented within a few days, but that the property manager has had trouble finding tenants because of crime in the neighborhood. He said the manager removes the central air-conditioning units and furnaces from the homes while they are vacant because thieves quickly strip vacant homes of anything valuable. The property manager boards houses as a matter of precaution, he said.

Joseph Hagan, president and CEO of National Equity Fund in Chicago, said three projects his group syndicated -- Toledo Homes I and II and Warren Sherman Flats -- have experienced tax recaptures.

Although tax credits are linked directly to individual homes, he declined to provide specific addresses for which recaptures had occurred. He also refused to give amounts or dates when recaptures took place.

He acknowledged there may be uninhabitable homes for which tax credits were received, but that such mistakes would be rare. National Equity Fund monitors the projects once a year to determine whether tax credits should be recaptured, he said, but poor communication from community developers sometimes results in a lack of access to the interior of the homes.

In fact, community developers sometimes hide poorly maintained units from their investors, he said.

"To say one gets missed once or twice -- it's very possible," he said. "You try to pick the best partners, but some of them are not up front with you. That happens. We do have partners that have not been communicative with us."

Kimberly Dobson, owner of Renee Co., managed Toledo Homes I and II for two years before the owner, a community development group called ONYX, fired and sued her. She accused the group of hiding several uninhabitable homes.

"They didn't disclose them," she said. "It had to be for at least a year or two, because those properties were completely destroyed."

Still, Mr. Hagan defended the tax credit program.

"There are three folks who are supposed to be monitoring this. The first is the developer. The second one is really the state. They are supposed to do their own inspections. The third is us," he said. "That's a pretty effective way of getting things done. It works well."

Contact Kate Giammarise at: kgiammarise@theblade.com or 419-724-6091.