SPECIAL REPORT: THE UGLY TRUTH ABOUT TOLEDO

Blight scars Toledo as residents, officials decry the mounting mess

6/15/2014

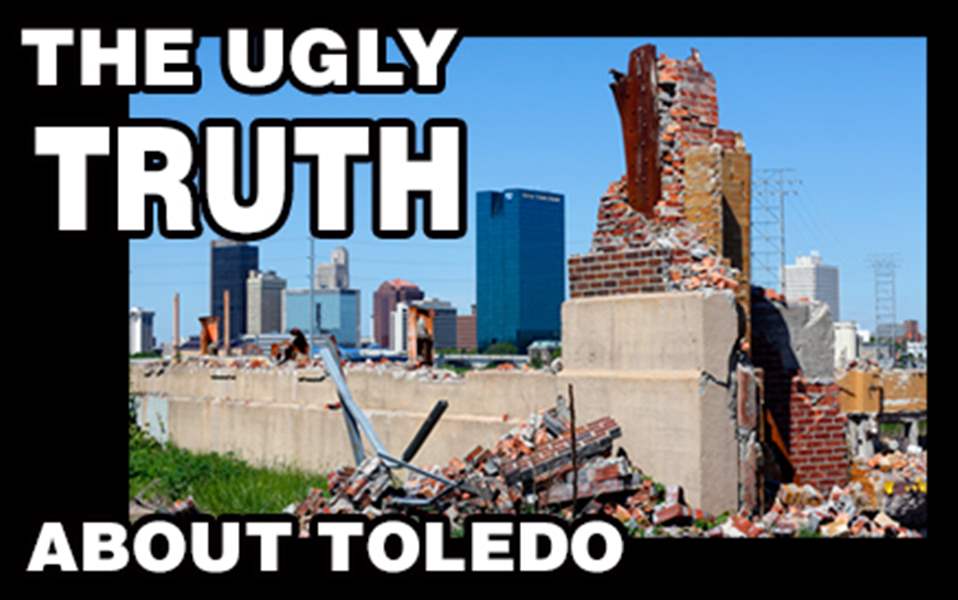

The downtown Toledo skyline is visible behind debris and ruins of the Toledo Edison Acme power plant along the Maumee River in East Toledo.

Today, The Blade turns its attention on blight in Toledo. By many measures, the city has been in decline for decades, but the most recent recession has hit Toledo hard. “The urban death spiral” is how Mayor D. Michael Collins labels it. We do this not to put Toledo in a bad light, but because the deterioration of our city is undeniable, and the community needs to begin a discussion about what it will take to fix the problems confronting us.

In neighborhoods festering with fear, residents hunker down behind doors and windows bolted with bars.

No amount of fancy ironwork can disguise the ugly reality.

For thousands of residents, Toledo has turned into a tattered town, a scary place where rats and raccoons scurry in tall weeds, where pimps, hookers, and gangs do business on street corners or in fancy cars cruising potholed streets.

Such deplorable conditions prompt Delores Kelly to avoid her front porch in her Avondale Avenue neighborhood. “What’s there to look at? Boarded up houses? Everyone is talking how the city is looking a lot like Detroit these days. Drugs, vacant houses, the homeless. People going into abandoned houses to smoke crack, to have sex. The neighborhood looks like a ghetto.”

Blight. Neighborhood blight, a boil on the city’s buttocks.

Shameful. Pitiful. Downright disgusting.

At first glance it seems bewildering that this has happened, but blight has shattered sections of the Glass City. The shine is off, the sparkle gone.

Blame abounds: recession, crime, white flight. Aging housing stock, aging homeowners. Slumlords. Lack of jobs. Crushing, inescapable poverty.

Fingers point to a passel of nincompoops. In friendlier terms: city officials who ignored the problem.

The Ugly Truth About Toledo page

Join the conversation by sharing your thoughts and photos of Toledo. Remember to note the location your photo was taken, and to include #UglyTruthToledo somewhere in your tweet, Facebook post, or Instagram photo. You can also e-mail your photos to uglytruthtoledo@theblade.com.

Tim Johnson mows a strip of yard next to his home in the 2000 block of Broadway in South Toledo. The house behind his home at 925 Harding Dr., in the background, caught fire more than five years ago and is still standing, to his frustration, and a house that once stood beside his house was torn down after a fire, but the grass is tall.

The problem has become a crisis, said Wade Kapszukiewicz, Lucas County treasurer and chairman of the Lucas County Land Bank. Created in August, 2010, the Land Bank typically acquires houses to demolish them or, when possible, convert them to other uses or sell them.

How serious is the crisis? A survey of the city’s 100,000 parcels under way should provide the answer.

Estimates are all over the map. About 4,000 to 5,000 abandoned houses. Or 2,000. As high as 9,000 unoccupied houses with numbers fluctuating as tenants move in, move out. The city’s lack of up-to-date housing stock data is “shocking,” said the county treasurer.

Escalation of vacant houses ripe for blight is tied to Toledo’s population. In 1970, the city had 383,000 residents. Forty years later, in 2010, that number had plummeted to 280,000. “In one generation we lost 100,000 people,” Mr. Kapszukiewicz said. “Simple math tells you there is more housing stock than there is population.”

Poverty statistics paint an even grimmer picture. In 1969, with dozens of factories bursting with workers taking home union wages, Toledo’s poverty rate stood at 10.9 percent. The poverty rate edged up to 13.6 percent in 1979; jumped to 19.1 percent in 1989; and by 2012, just out of the Great Recession, reached 26.8 percent — with 75,158 people living in poverty in the city.

With such a decline in population and in residents making a decent living, Toledo’s challenge with abandoned structures and blight has turned from problem to crisis, Mr. Kapszukiewicz said.

A shopping cart occupies a spot at the site of the demolished North Towne Square Mall along Alexis Road.

Mayor D. Michael Collins said he wouldn’t go as far as to call the situation a crisis, but after a review of photographs taken by The Blade of blight in the city, he said: “While we are in a fiscal recovery we still have not been capable of reversing what I have identified to be the urban death spiral.”

“Toledo has accepted for far too long a government that has managed the city with decline being the normal. I totally reject that concept, and my commitment is to manage a city that is on the incline, and the stabilization of neighborhoods is critical to that philosophy,” the mayor said.

He added that his challenge over the next 3½ years is to very aggressively enforce all nuisance and code violations using the joint resources of the police and code inspectors.

Mr. Collins described his job as managing a cafeteria. Would you like potholes with your tall grass? Or a side of abandoned property issues?

He said the city is working to make improvements through a new program set to begin next month. A joint effort, the program teams city code inspectors with police officers. During his mayoral campaign Mr. Collins often touted a plan to clean up the city, an initiative he repeatedly called “Tidy Town.”

Anyone driving through many parts of the city would say Mr. Collins has a long way to go before the city could be called tidy.

Razing structures

Demolition work is taking down hundreds of structures, but it seems barely a ripple in a stagnant sea of blight.

Since August, 2012, nearly 840 structures in Toledo have been torn down at a cost of nearly $6.8 million. In the Land Bank’s second phase, 600 more eyesores are to be demolished.

Writing on a boarded-up house at 2314 N. Erie St in North Toledo informs would-be intruders that valuable materials already have been stripped from the structure.

Weary of waiting, residents ask: When will the bulldozers get to my neighborhood?

As some residents in downtrodden areas keep houses repaired and yards trimmed, others shrug. Who the hell cares in a world seemingly flushed down a dirty toilet. Call city hall? Why bother.

When residents stop complaining it means residents have given up, said former Mayor Carty Finkbeiner, known for his “Dirty Dozen” committee that would identify Toledo’s top 12 decrepit commercial, industrial, and residential properties and pressure owners to rehabilitate the buildings or tear them down.

He recommends tougher laws against trash dumping and stricter laws for criminals who strip homes of building materials and for scrap dealers who purchase the stolen items.

The former mayor also said officials need to earmark Community Development Block Grant funds to support blight removal and create a central fund for public and private dollars dedicated to nuisance abatement.

In East Toledo, 307 Parker Ave. caught fire months ago, and debris from the structure remains in front of it.

He would like to see city officials and inspectors out and about regularly to observe areas where most complaints originate. Without weekly reports and progress updates, efforts to address the problem stall, he said.

When shown photographs taken by The Blade of blighted areas of Toledo, Mr. Finkbeiner said such deplorable conditions would have been cleaned up under his administration, even if it took repeated efforts to get results.

A photograph of a dilapidated factory prompted him to say that the owner should be encouraged to address the blight. “We would not have let the owner off the hook,” he said, noting the factory would have made good money when it was open and it would be worthwhile to pursue a resolution, be it demolition or other remedies.

Mr. Finkbeiner said property owners must be held accountable and that residents have the responsibility to the rest of the community to do better than this. “That’s terrible. That’s a disaster,” he said after viewing Blade photographs of blight on Ontario Street in North Toledo. “We didn’t tolerate this.”

Another former Toledo mayor, Jack Ford, now chairman of City Council’s neighborhoods committee, said the city should step up and take care of problems such as high grass or clearing trash.

“The mayor will say they don’t have money, but they do have money,” he said. “The grass is something that can be done.”

For District 6 Councilman Lindsay Webb, who represents Point Place, this issue is personal.

“These pictures and the blight in our community should have an emotional impact on members of council,” Ms. Webb said. “Either because they remember the neighborhood in its former glory or because the pictures serve as a reminder of the growing poverty in our community.”

Depressing scene

No doubt blight abounds in Toledo, where hundreds, if not thousands, of stores, factories, houses, and other buildings crumble under the weight of neglect. Decrepit and dangerous. Neighborhoods as junkyards.

Urine-scented sidewalks, broken foundations, smashed windows, boarded up front doors, scattered shingles, heaps of rotting furniture.

What a mess, what a depressing, deplorable mess.

It is about what you see. And what you can’t. Despair lives here, not as an overnight guest but as permanent resident.

The impact, and the cost, goes well beyond bricks and mortar. This crisis is about people.

Neighbors Amelia Wetzel, 8, and Nick Wood, 7, take Nick’s 13-year-old mix Gotti for a walk through the weeds at an abandoned house in the 300 block of East Broadway Street in East Toledo.

Blemishes scar the face of the community — emotionally, physically, socially, economically.

“It makes my house look trashy,” said Ms. Kelly, about blight in her central-city neighborhood. “I don’t deserve this. People who own homes or rent homes don’t deserve this.”

Her home is as cozy, neat, and clean as they come. And there is something very special about a home where large teddy bears sit around a dining room table, awaiting a cup of tea and perhaps a cookie or two.

Stark contrast indeed to the sign in her window — Beware. Pitbull with AIDS — and to the wrought-iron steel bars on her doors and windows. It is like living in a bunker.

“We need something done. It’s been annoying, big time,” said Terese Hurst, 36, who rented last December an affordable home on Parker Avenue in East Toledo. In January, fire damaged a house next door, where charred wood, clothing, and furniture remain on the front lawn. “All that garbage flies in our yard.”

She cringes when friends drop her off at her home. People say the neighborhood looks like “crap.” They ask: “You live here?”

“Toledo needs to be cleaned up,” Miss Hurst said. “There is nothing but abandoned, boarded up houses. It is ridiculous. I want to leave. This town sucks.”

Buildings worth saving should be renovated, she said. Improve the looks of the neighborhoods, entice businesses to open and offer jobs. “That would be awesome.”

Weeds have overtaken the playground of the former Toledo Day Nursery at 219 Southard Ave. near downtown Toledo.

The ‘same boat’

Toledo is not alone in this struggle.

“We’re all in the same boat,” said Rob Fischer, co-director for the Center on Urban Poverty and Community Development at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, as he talked about key Ohio communities, such as Cleveland and Toledo, where population loss and the housing crisis are impacting neighborhoods, hand in hand.

Population loss is occurring in part because of the housing crisis, and banks, he said, are not structured to be landowners or property owners. “They don’t want to be in the business of holding these properties. Banks don’t make good holders of property,” Mr. Fischer said.

He said in sections of Cleveland, there are areas where only two residents remain on a block.

The same lack of residents is taking place in Toledo, several residents told The Blade.

And this, Mr. Fischer said, creates residential islands in some neighborhoods. Efforts to secure properties can be difficult at best as vacant houses become victims of criminals who come in to strip out copper pipes, for instance. Then, further declines occurs.

Cleveland has 10,000 structures that are structurally unsound, he said, and the debate is whether to demolish or rehabilitate, which can be more expensive.

After looking at photographs showing a sampling of Toledo buildings in disrepair, Mr. Fischer said the images were typical of the blight in many cities.

“These are very comparable to what we see in other neighborhoods that are facing this,” he said. “I see the same kind of conditions in many of our neighborhoods in Cleveland and I have seen images of Detroit like this.”

Mr. Fischer said the concentration of blighted homes and structures is important to consider when assessing the problem.

Many cities have “pockets of blight,” he said, while those in worse shape have whole swaths of burned-out and boarded-up homes, high weeds, and trash.

Children play near an abandoned home at 951 Prouty Ave. in South Toledo.

Mr. Fischer was unaware of an overall ranking list of cities based on blight, but Cleveland is having the same debate that the survey of Toledo homes is likely to spark.

The pattern of housing decline in Toledo coupled with population decline “is pretty common in metropolitan areas where the level of housing construction runs far ahead of household growth,” said Rolf Pendall, director of the Metropolitan Housing & Communities Policy Center at the Urban Institute in Washington.

The problem is likely to accelerate in the next 20 years in Toledo and the Great Lakes area because so much of the area’s housing is occupied by people born before 1955 or so, and those residents will want to downsize, or they will age in place and then die. Many 20 and 30-somethings have been migrating away from there for several decades, and so there are some limits on how many new households will enter the housing market, Mr. Pendall said.

Fighting blight

Some people work hard to improve their properties.

Tom Schwartz, an area contractor, brushed paint on a renovated home’s wooden slats near the porch.

Blight? He’s seen more than he ever thought possible in Toledo. He faults an overabundance of rental properties and absentee landowners. “But a lot is the economy. Owners do not have money to keep up. It’s a shame.” Some poor people have to decide: eat or make the house look nice. They lack money to do both, he noted.

Speculators who snapped up properties at the height of the housing bubble have left structures to rot. Landlords unable or unwilling to maintain rental units walked away from properties. Homeowners battered by the economy have fled town, leaving behind unpaid mortgages.

For the last two years, when Tiffany Bolczak, 26, looks out the kitchen window of her Talbot Street home in West Toledo, she sees a boarded up, vacant house. ‘It’s really terrible,’ she says.

On Talbot Street near Woodlawn cemetery in West Toledo, Tiffany Bolczak, 26, looks out her kitchen window. The scene has been the same every day for two years: a boarded up, vacant house. “It’s really terrible,” she said. Several other vacant homes drag down the look of the neighborhood.

Sections of Toledo scream out: Bring on the bulldozers. Other areas? Sadness creeps in. Broken homes, broken-down lives. No economic uplift here.

Housing stock ages by the day. Not a graceful sort of growing old, but rather bone-weary old, too tired to care. Residents are older too and poorer. It would cost money — money they don’t have — to pay someone to maintain their homes, to mow the grass, to fix dangling gutters, to repair the roof, to remove piles of discarded furniture.

In the worst of the worst neighborhoods, listen closely. You can hear it. The death rattle.

“We’ve got rats, mice, cockroaches now in vacant homes. It got bad in the north end and people moved here and the south end started to look like the north end. Then people moved to the east side and it looks like the bad areas of the south side. The only decent area is the Old West End,” said Terry Carroll, 50, who lives in the south end. Blight is up as well as crime, he said. “Robberies left and right. You can’t even leave your door unlocked anymore. Not for a second.”

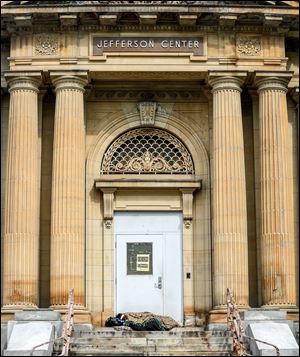

A woman sleeps on the steps of the Jefferson Center on Jefferson Avenue in downtown Toledo.

Some of the worst blight in Toledo is in neighborhoods controlled by the more than two dozen gangs that claim them as their territory.

On a recent day, Mr. Carroll helped haul bricks from a demolished building to the nearby future home of Western Avenue Ministries. The bricks, Mr. Carroll said, will dress up the front of the building and help protect it from thugs.

Rusty signs on utility poles are half right: Now Entering A Weed & Seed Community.

Tall and overgrown, weeds clog properties, not just in residential areas, but on blighted commercial or industrial properties where mammoth, ramshackle factories sprawl across pockmarked lots dotted with empty whiskey and wine bottles, used condoms, beer cans, and fast-food wrappers.

Ghosts of the past haunt the skeletons of once bustling, thriving factories. In areas where workers once assembled or manufactured this or that, trees tower through long-gone roofs. Pelted with rocks by vandals, windows gape with holes. Pretty, it ain’t.

Stop the blight, residents cry out. Make it stop.

Contact Janet Romaker at: jromaker@theblade.com or 419-724-6006.