Water crisis grips hundreds of thousands in Toledo area, state of emergency declared

8/3/2014

Donald White hauls off water he purchased at Walgreens on Monroe Street on Saturday.

THE BLADE/ANDY MORRISON

Buy This Image

Donald White hauls off water he purchased at Walgreens on Monroe Street on Saturday.

Corrected version: Measurement results were changed to parts per billion.

A once-unthinkable crisis in the world’s greatest freshwater region — one that sent more than 500,000 metro Toledo residents scrambling for bottled water Saturday — enters its second day today, with officials inside the city’s Collins Park Water Treatment Plant wondering how much longer it will take before clean, safe, and reliable tap water will flow again from faucets of area homes and businesses.

“We’ve been getting mixed results,” Jeff Martin, a senior chemist at the plant, confessed during an exclusive interview with The Blade on Saturday while performing tests for microcystin — a toxin produced by the harmful blue-green algae known as microcystis — inside the plant’s laboratory on samples drawn from 39 metro Toledo sites.

GET SOCIAL: Join the conversation using #emptyGlassCity

RELATED: Rest of region on high alert

RELATED: Volunteers pour into region to offer help

RELATED: Emergency’s impact on business

COMMENTARY: What do we know? And when will we know more?

The cause of the microcystis algae bloom is primarily phosphorus from farm fertilizer runoff, and the amount of phosphorus determines the bloom’s size. Scientists are also learning that another farm fertilizer, nitrogen, affects the size and composition of the annual bloom.

Toledo sits on the shoreline of the Great Lakes, which holds 20 percent of the world’s fresh surface water.

A small water treatment plant in Ottawa County’s Carroll Township was Ohio’s first to be overwhelmed by the toxin last September.

Until 2 a.m. Saturday, city and state environmental officials maintained such a crisis was unlikely in Toledo because the water plant is western Lake Erie’s largest and most sophisticated.

But after seeing symptoms of a problem emerge late Friday — a series of suspicious test results that showed a pattern of contamination — officials were told by the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency to issue the city’s first “do not drink” or boil warning to the system’s customers.

The warning went out on Facebook, followed by a series of news conferences.

Toledo Mayor D. Michael Collins said he was notified about 10 p.m. Friday that the numbers weren’t good — even though the algae season has barely begun.

About midnight, he heard of the Ohio EPA’s plans to issue a warning against drinking the water.

RELATED: Day’s events recorded on social media

RELATED: Hospitals see rise in patients

RELATED: Community alert systems delivered news

“I don’t believe we’ll ever be back to normal,” the mayor said during an evening news conference. “But this is not going to be our new normal. We’re going to fix this. Our city is not going to be abandoned.”

For most of Saturday, Mr. Collins and others conferred among themselves and via phone with Gov. John Kasich from the Lucas County Emergency Services Building near downtown after the governor had declared a state of emergency.

Meanwhile, confusion reigned inside the Toledo water treatment plant, with no clear answers if other water systems in the western Lake Erie region were in danger of a similar crisis or if Toledo might have possibly had a series of false positives because of the federal EPA’s failure to settle on standard testing protocol.

Water plant operators from Monroe to Sandusky have been urging the federal regulatory agency to develop a testing standard, asserting they are the public’s last line of defense but are left without knowing the best way to test for microcystin.

PHOTO GALLERY: Water advisory impacts Toledo area

PHOTO GALLERY: More of Toledo water crisis

“They have just been sort of waffling on it,” Mr. Martin said about the U.S. EPA.

The federal agency has said it is still months away from finalizing such a standard.

Toledo has an eight-phase treatment process.

People buy water in the Dixie Highway Kroger in Frenchtown Township in Monroe County.

The chemical permanganate is applied in the water-intake crib 3 miles north of the shoreline, starting the treatment process before the water even gets to the plant, which can take six to 12 hours. The length of time aids in reducing contaminants, officials said.

Along the way, the raw lake water is treated with powdered activated carbon, mostly for taste and odor; alum, to bind particles together and make them easier to remove; lime, to reduce hardness; soda ash, to neutralize excess alum; polyphosphate for stability; chlorine, for disinfection, and fluoride, to combat tooth decay.

The decision on when Toledo’s water is going to be safe enough to drink again is “basically going to be the Ohio EPA’s call,” a weary Jeff Calmes, the plant’s administrator of operations, said after being up more than 38 consecutive hours.

Depending on the results, the same treatment process could be used.

The Ohio EPA is awaiting results of samples sent off to a U.S. EPA laboratory in Cincinnati, a state EPA lab in Columbus, and a lab at Lake Superior State University in Sault Ste. Marie, Mich., before making that call.

“At this point, we’re waiting on test results,” Andy McClure, plant superintendent, said.

Data from tests performed by Toledo and Oregon are “very confusing for everyone,” Mr. Collins said.

“We really don’t have a true answer. One set of tests is different from the other,” he said. “... We don’t know for sure [whether] these [city] tests are proof positive, but certainly we’re not taking any risks.”

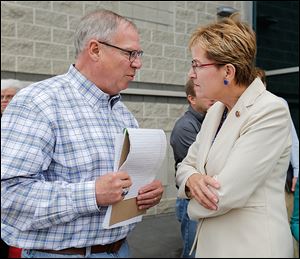

Toledo Mayor D. Michael Collins speaks with U.S. Rep. Marcy Kaptur outside the Lucas County Emergency Management Agency building.

Mr. Collins said he will not tell Toledo residents to resume drinking water from their taps until he is convinced it is safe enough for children.

Water was expected to be available again today at several locations, including Woodmore, Waite, Central Catholic, and Springfield high schools, as well as at least two fire stations in Oregon.

At the Collins Park water-treatment plant, Mr. Calmes was one of many employees distressed by the ordeal.

Many were going on little or no sleep.

“We’ve got a very dedicated work force,” Mr. Calmes said. “It’s an ‘all-hands-on-deck’ mentality here today.”

Records show the first sign of microcystin inside the Collins Park Water Treatment Plant appeared on July 6, when a reading barely high enough to be detected by the plant’s technology was recorded.

That, in itself, is not unusual. The toxin has been found at low levels before inside the plant since 1995, when microcystis reappeared in western Lake Erie after a 20-year absence.

The toxin appeared again inside the water plant between July 15 and 18.

But until Saturday, it never was known to slip through the plant’s multi-staged treatment process.

That triggered the region’s largest known water crisis, which prompted many residents to begin scrambling for bottled water hours before dawn.

Shortly after the bulletin was put online at 2 a.m. Saturday, residents emptied shelves of bottled water in grocery stores and carryouts within about a 100-mile radius.

Water that had been destined for other parts of the state was diverted to northwest Ohio so stores could restock. The National Guard trucked in water from Akron and Piqua, which is north of Dayton. Premixed formula and military meals were delivered to Toledo from Columbus.

Water stations were set up at high schools, fire stations, and even unannounced locations around the area.

The Village of Pioneer in western Williams County made one of the most generous offers of the day: They said they would make 600,000 gallons of potable water available every 24 hours. Those interested must bring their own trucks, containers, or bottles to 409 First St. in the village.

Restaurants in the affected area were urged to close unless they can guarantee no consumption of tap water. Bottled water shipments that were destined to other regions were rerouted to Toledo, said Kroger spokesman Jackie Siekmann.

Joe Andrews, Ohio Department of Public Safety spokesman, said the Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Corrections had converted its milk-bottling plant near Columbus to package drinking water in large bladders.

Dr. David Grossman, director of the Toledo-Lucas County Health Department, said a safe level of microcystin is 0, but an allowable level is below 1 parts per billion.

At the Collins Park plant, water was testing as high as 2.5 parts per billion, he said.

Toledo-area hospitals reported more than 100 people sought treatment in emergency rooms by late afternoon, concerned that they were ill from ingesting contaminated water. Some displayed symptoms such as upset stomach, dizziness, and vomiting.

When word went out Saturday morning that Toledo’s tap water was contaminated, Garrett Wieland, of Toledo, heard the news just before 8 a.m. and yelled to his girlfriend not to get in the shower. He then headed out in search of bottled water, ending up a couple blocks from home at the Walgreen at 4580 Monroe St.

He was among a crowd of shoppers who had heard the store had bottled water available, but found the clerks were selling water that had yet to arrive on a truck from the distribution center south of Toledo. Sales were limited to five cases of 24-ounce water bottles per customer and sold out within minutes.

“We were lucky to get some,” Mr. Wieland said. “The line was just crazy, and things got a little heated in there.”

Hope Gonzalez, who lives in the Old West End, also was among the shoppers who waited, sometimes sitting on overturned shopping carts or chairs and milk crates that Walgreen employees brought out from the store.

“Lesson learned,” Ms. Gonzalez said. “I will always be buying water every time I go to the store now. We’re never getting caught without some water in the house again.”

Blade staff writers Taylor Dungjen, Wynne Everett, Marlene Harris-Taylor, and David Patch contributed to this report.

Contact Tom Henry at: thenry@theblade.com or 419-724-6079.