Algae’s lake effect reveals pea green disaster

Rapid deterioration creates concern for Toledo community

8/4/2014

Algae is visible in Lake Erie near the Toledo water intake crib. The color of the water illustrated the problems to the officials and media on the tour.

THE BLADE/DAVE ZAPOTOSKY

Buy This Image

Shane Gaghen of Oregon holds a glass of algae filled Lake Erie water near the Toledo water intake crib on Sunday. The National Wildlife Federation conducted a media boat tour of the area.

The most telling sign of western Lake Erie‘s sickness comes from an up-close view of the putrid, bright green algae surrounding Toledo‘s water-intake crib, not from the multiple updates provided by public officials in front of television cameras outside of the Lucas County Emergency Services Building.

The lake’s rapid deterioration 2 miles off the Toledo shoreline created a gripping sight on Sunday for about 20 people — a combination of journalists, elected officials, and environmentalists — aboard a vessel captained by Vern Meinke, owner of Meinke Marina, of Curtice, Ohio.

Many of them compared the lake’s current color to that of pea soup. As Mr. Meinke’s boat plied the water, waves behind it looked like thick, green paint.

“What we’ve experienced here shows us this is a dangerous situation,” Toledo Councilman Larry Sykes said.

He’s not known for being a rabid environmentalist, nor is he known for failing to speak his mind. He seemed utterly dumbfounded how such a beautiful body of water could be transformed into sheer ugliness virtually overnight, fouled by a toxic form of algae known as microcystis that is fed by excessive phosphorus from farm runoff, lawn fertilizers, and sewage overflows.

VIDEO: Toledo-area water crisis

PHOTO GALLERIES:

■ Kasich, Collins comment as Toledo water crisis continues

■ Toledoans still scurrying for water supplies

■ Algae at Toledo water intake crib

■ Oregon water treatment facility

The lake tour took place on the second day of Toledo’s drinking-water ban that affects 500,000 area residents because of high levels of algae toxins found in samples taken from the city’s treated water system.

Ironically, the city council on Monday gets its first look at a rate increase to finish off the final third of Toledo‘s historic $521 million sewage expansion project known as the Toledo Waterways Initiative, which is intended to steeply reduce sewage overflows that contribute to the algae’s growth.

“It’s a no-brainer,” Ohio Rep. Mike Sheehy (D., Oregon) said.

For Mr. Sykes, from a poor part of Toledo who often has said he was one bad break away from engaging in a life of crime instead of growing up to become a businessmen and politician the emergency declared over the city‘s tap water has overtones of what happened to New Orleans residents in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina in 2005.

Maybe not as much chaos. But a heck of a lot of inconvenience.

“Nobody wants this on their watch,” he said. “We ducked a bullet. It could have been mass craziness.”

Public officials who were ambivalent about environmental issues have been served a wake-up call, Mr. Sykes said.

“They’re listening now. It‘s going to be like a corn field — a lot of ears,” he laughed.

Back at the Lucas County Emergency Services Building, Toledo Mayor D. Michael Collins congratulated the Toledo area for showing its “mettle” by generally handling the crisis without incident. He said the police department had no major outbursts or reports of violence it could attribute to a water shortage.

Like many city employees, Mayor Collins was worn down and sleep-deprived from the ordeal. He started the day by noting the chief chemist at the Collins Park Water Treatment Plant, Brenda Snyder — whom he said has earned his rock-solid confidence — finally went home to sleep after working 40 consecutive hours at the water plant mulling over test results. Mr. Collins, who worked past midnight Saturday, was back on the job after a few short hours. Late Sunday night, he told The Blade he was planning to update the media on the latest water test results about 1:15 a.m. today.

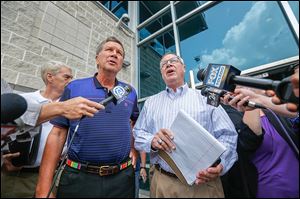

Ohio Gov. John Kasich, left, and Mayor D. Michael Collins said after a closed-door meeting that they won’t declare the emergency over until they are reassured.

Lack of sleep

By early Sunday night, his public relations director, Lisa Ward, confessed Mayor Collins was getting a “little punchy” from lack of sleep.

Few new developments occurred Sunday beyond U.S. Rep. Marcy Kaptur (D., Toledo) saying she heard in passing from a U.S. Environmental Protection Agency official that Toledo’s tap water registered microcystin toxin levels as high as 3 parts per billion when the crisis began, higher than the range of 1.5 ppb to 2.5 ppb announced in a Toledo-Lucas County Health Department statement on Saturday and three times the World Health Organization’s cutoff of 1 ppb for safe drinking water.

Miss Kaptur said she is calling on state and federal regulators to release testing data. Even as a congressman, she said, she has not been provided test results by the U.S. EPA or the Ohio EPA. She said the information about the spike in microcystin reaching 3 ppb appeared to be a slip of the tongue during a conference call.

“In all of the meetings we’ve sat in, we’ve been given nothing,” Miss Kaptur told The Blade. “Every time I asked [the U.S. EPA] to provide information, they deferred us to the Ohio EPA. We’ve not been given anything tangible.”

Mayor Collins has been apprised of the results. He said he does not intend to release them publicly until after the threat has passed because he doesn’t want people second-guessing him or the governor’s office over the number of tests that have come back normal.

Part of the confusion is the different testing protocols being used at each lab. Plant operators are frustrated by the U.S. EPA’s failure to develop a standard testing protocol.

Collin O’Mara, president and CEO of the National Wildlife Federation, points out algae blooms near the Toledo water intake crib in Lake Erie. The algae bloom season is just beginning.

No exact tests

“There are no exact tests. There is no exact protocol,” said Gov. John Kasich, who visited Toledo on Sunday and joined Mr. Collins at one of the news conferences.

Mr. Collins said he was not familiar with the information Miss Kaptur passed along about the microcystin spike of 3 ppb.

“I don’t remember what the exact numbers were and that’‘s the truth,” he said. “I’m getting hit with so many numbers.”

Mr. Collins and Mr. Kasich said they will not be pressured into releasing results or declaring the emergency over until they are assured the water is safe to drink again.

“When we’re comfortable with what we see, that’s when we will make that decision,” Mr. Kasich said. “We’re all one community and one family. We are not going to get off this [emergency declaration] until it’s time to do so.”

The two also don’t want to declare another emergency.

But is that possible to avoid?

Algae is visible in Lake Erie near the Toledo water intake crib. The color of the water illustrated the problems to the officials and media on the tour.

Season starting

Great Lakes scientists who have been tracking western Lake Erie’s algae since 1995 have noted that the region has only begun its traditional algae season.

Blooms such as those spotted around Toledo’s water-intake crib on Sunday often don’t peak until late September, although the Toledo area — the shallowest part of the lake — usually gets algae outbreaks first before they move eastward toward the —Lake Erie islands.

The algae has been arriving earlier and staying later in the past decade, which scientists consider a symptom of climate change.

“We’ve been dealing with a problem that is probably not in full bloom,” said Dr. David Grossman, Toledo-Lucas County health commissioner.

Officials have only begun to assess the hidden costs of pollution associated with this outbreak.

But everyone — including Mayor Collins and Governor Kasich — describe them as astronomical, considering all of the manpower expended on calling in city employees for the weekend, getting assistance from the Ohio National Guard, the Ohio Highway Patrol and local police and sheriff’s deputies and the untold millions of dollars Toledo-area restaurants and other businesses lost being forced to shut down during a busy weekend of summer.

Mr. Kasich said the costs of Lake Erie pollution are an eye-opener but that won’t change his vision of being a pragmatic leader who considers himself a staunch defender of Lake Erie even if he doesn‘t see eye-to-eye with environmental lobbyists on every issue.

Take care of lake

“My thinking isn’t reshaped because I consider myself an environmentalist,” he said. “I love Lake Erie. Our job’s not to worship it. Our job’s to take care of it.”

For the average homeowner, it is “doubtful” they will receive a break from the city on water rates during the next billing cycle because of the drinking advisory, Ms. Ward said.

Algae blooms were once far more predictable.

In the 1960s, when Lake Erie was nearly declared a “dead” body of water because of how excessive algae robbed so much oxygen from the water column, contributing to massive fish die-offs from other forms of industrial pollution, it was an easier fix. The region installed better sewage controls.

Better sewage controls are the heart of the federal Clean Water Act of 1972 and a similar landmark pact made with Canada that year, the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement. The Clean Water Act, though under attack by predominately Republicans in Congress, remains one of the nation’s landmark laws. That law and the companion agreement with Canada, signed by then-President Richard Nixon and then-Canadian Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau, signaled a new era in sewage treatment and have been largely hailed for making Lake Erie’s comeback one of the greatest success stories of the end of last century.

But the lake quality has been on a downward slope since toxic microcystis algal blooms began reappearing in 1995, the same time Heidelberg University began noticing a steady increase in phosphorus loading into the Maumee River from area farms.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and scientists at Ohio State University’s Stone Laboratory on Gibraltar Island, near Put-in-Bay, have seen more irregularities in algae blooms since 2003, even though western Lake Erie’s had outbreaks nearly annually for the past 19 years.

Theories abound, from the impact of non-native zebra mussels and another exotic that has displaced them, the similar — yet larger — quagga mussels. Their excretions contain as much phosphorus as what they take in, meaning it’s being passed through their systems without being digested.

More recently, impacts of climate change are becoming a greater focus.

Collin O’Mara, National Wildlife Federation president and chief executive officer, said there’s “a systematic challenge we face here in the Great Lakes that’s much bigger” than Toledo’s immediate water crisis and that’s climate change.

“If we don’t get our arms around it, we will see property values decline, tourism decline, and more wildlife impacted,” he said. “I encourage everyone to consider the broader issues.”

Sandy Bihn, founder of the Lake Erie Waterkeeper group, said she believes internal loading of phosphorus is where the scientific research for Lake Erie is headed.

She said it’s scary to think that even massive reductions in runoff won’t do the trick.

“You can’t treat the lake sediment once the phosphorus is in there,” Ms. Bihn said. “There is no model for addressing internal loading in the lake.”

She called it a “warning sign” for the rest of the Great Lakes.

Contact Tom Henry at: thenry@theblade.com or 419-724-6079.