Toxin tests vary

May be why Oregon was able to treat early

8/4/2014

Wagner

THE BLADE/DAVE ZAPOTOSKY

Buy This Image

Doug Wagner, Oregon’s water plant superintendent, theorized that the red-flag test results Toledo got late Friday into early Saturday — results that prompted a no-drink warning for Toledo’s more than 500,000 water customers — were caused by some change in how the neighboring water system tests for microcystin, rather than an abrupt change in the toxin’s level.

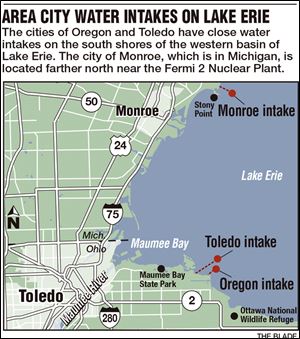

Measurable levels of microcystin, the toxin emitted by blue-green algae now blooming in Lake Erie’s western basin, began turning up in Oregon’s untreated water intake in mid-July and reached levels warranting more frequent testing last week, Oregon officials said on Sunday.

But Oregon’s water treatment plant had begun treating the water for microcystin before it even turned up in the intake because a city official had noticed the developing algae bloom while out boating on the lake, said Doug Wagner, Oregon’s water plant superintendent.

VIDEO: Toledo-area water crisis

PHOTO GALLERIES:

■ Oregon‘s water treatment facility

■ Kasich, Collins comment as Toledo water crisis continues

■ Toledoans still scurrying for water supplies

■ Algae at Toledo water intake crib

What matters most, said Mr. Wagner and Paul Roman, Oregon’s director of public service, is that with treatment, microcystin has not been detected in Oregon’s treated water supply — unlike that of neighboring Toledo, which draws its raw drinking water from an intake only about a mile farther away in Lake Erie.

Mr. Wagner theorized that the red-flag test results Toledo got late Friday into early Saturday — results that prompted a no-drink warning for Toledo’s more than 500,000 water customers — were caused by some change in how the neighboring water system tests for microcystin, rather than an abrupt change in the toxin’s level.

“I can’t speak for what happens in Toledo, but I suspect something changed between Thursday and Friday” in how the test is conducted there, Mr. Wagner said.

But part of the problem with managing the algae toxin is that while minuscule concentrations have been deemed dangerous for drinking, the testing is imprecise, and lake conditions can be variable within small areas and short time periods, the Oregon plant superintendent said.

Wagner

Authorities testing for the 20 parts per billion — ppb — threshold at which skin contact with the toxin is considered dangerous can use test strips that change color if the toxin is that concentrated, Mr. Wagner said.

Roman

But for the 1 ppb level generally accepted for safe drinking water, he said, “the test is very, very subjective. If you look at it funny, you get a different result.”

The mere presence of algae, meanwhile, does not guarantee the presence of its toxin, he said.

It’s a mystery how the algae becomes toxic and how it changes, and when there is toxin it can be strong in one place and nonexistent nearby, Mr. Wagner said.

With such changeable conditions, it might seem appropriate to test frequently during algae blooms, but the plant superintendent said the test is time-consuming.

That’s why Oregon normally performs the test just once a week, he said, even though it has a laboratory at its plant, unless toxin concentrations in test samples start to rise.

“It takes about four hours to do one run,” Mr. Wagner said.

Before 2010, Oregon sent its samples to the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency, which meant a significantly longer response time for results.

While the cost of equipping its own lab for the microcystin testing was $10,000, “that investment is definitely paying off,” said Mr. Roman.

With Oregon’s untreated intake water sample from Wednesday testing at between 15 and 20 ppb, Oregon now will run the test for toxins at least three times per week, he said, and during those tests it may run samples from the days in between as well.

A Toledo water plant official did not respond to a request for comment Sunday evening about Mr. Wagner’s theory.

Toledo officials have released no data from its own tests or testing performed by other agencies on Toledo water since the water crisis began.

As of Sunday evening, city leaders remained sequestered at the Lucas County Emergency Services Building awaiting further test results and planning their response.

After Toledo’s no-drink order was issued Saturday, Oregon did an immediate test, and its raw-water intake microcystin level registered then at 14 ppb, Mr. Wagner said.

Oregon also tests water samples from treatment plants in other nearby communities, including the Carroll Township, Ottawa County, Clyde, Ohio, and Monroe water utilities.

So far, those data show detectable levels of microcystin first appeared Wednesday in the untreated water from Monroe and Carroll Township, in Ottawa County, but well below Oregon’s sample from that day — 2.4 ppb for Carroll and 3.43 ppb for Monroe.

Clyde has had several detectable but low readings in its raw water in recent weeks too.

Treated water from those communities has not shown any detectable microcystin, Mr. Wagner said.

One thing that will not solve the microcystin problem, the plant manager said, is a windy day, even if the wind blows out of the southwest.

While that theoretically might push the algae away from Oregon’s water intake — as well as Toledo’s — resulting wave action would churn up the water and send the algae and its toxin deeper into the water and thus closer to those intakes, Mr. Wagner said.

At normal lake levels, Oregon’s intake crib is about 14 feet below the surface of Lake Erie, Mr. Wagner said, adding that Toledo’s intake crib is perhaps slightly deeper.

“With calm conditions, a bloom will just be on the surface, and that’s good for us. Storms stir it up, send it deeper, and it releases more toxin,” Mr. Wagner said.

Contact David Patch at: dpatch@theblade.com or 419-724-6094.