Toledo water intake crib was once a home

Caretaker lived there 7 years

8/23/2015

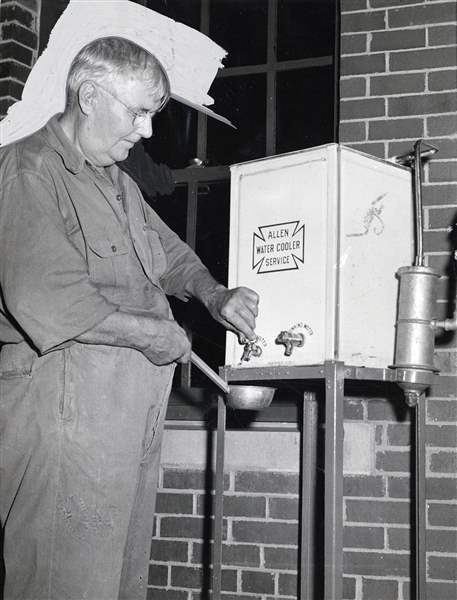

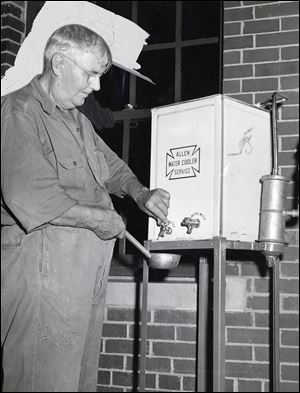

Montgomery Rabbitt, shown in 1942, was Toledo's original, and only, Lake Erie intake crib tender. He and his family lived in the structure for seven years.

THE BLADE/ARCHIVE

Buy This Image

Montgomery Rabbitt, shown in 1942, was Toledo's original, and only, Lake Erie intake crib tender. He and his family lived in the structure for seven years.

Toledo's water intake crib — once known as the “Fortress in the Lake” — was a celebrated engineering marvel in 1941 when the Lake Erie structure was dedicated.

But today, the structure sitting three miles from shore in Lake Erie is known as the mouth of a water system that failed the public for nearly three days last year when a harmful algal bloom settled around the intake and toxins fouled the water supply.

Click to read: History of the Toledo Lake Erie Water Supply System

From the exterior, its solid appearance conceals a deteriorating living space that once housed the only people to reside in the structure around-the-clock, year-round for seven years until 67 years ago.

In the 1940s, the intake crib building was home to the Rabbitt family, who meticulously cared for the circular concrete and steel structure.

“Monty Rabbitt has become kind of a legend,” said Andy McClure, administrator of the city's Collins Park Water Treatment Plant. “He was the only crib caretaker the city has ever had. After he died, he wasn't replaced.”

Toledo water intake crib in Lake Erie.

Mr. Rabbitt died May 15, 1948, at the age of 72. His wife used a phone that connected with the city Waterworks Division to call for help when she found her husband dead. Newspaper reports said the city was unable to find someone else willing to live in the structure, so maintenance and equipment tests were done with crews sent by boat.

The water system went online in 1941 — after a $9.88 million public investment — and Montgomery Rabbitt, an experienced diver, took the job as the city's first cribtaker. With his son Michael as an assistant and with his wife, Wilhelmina, by his side, Mr. Rabbitt was charged with maintaining the steady flow of lake water to the city's low service pump station via a submerged 108-inch wide tunnel and then on to the water treatment plant.

City officials had discussed a new lake water system in the 1920s. George Schoonmaker, Toledo's waterworks engineer in the late 1930s, told a Blade reporter a lake intake was needed because water taken from the Maumee River was inadequate, unsatisfactory, and too expensive to treat.

The new intake system took four years to build, beginning in 1938 and finally dedicated on Oct. 5, 1941. Newspaper reports from the time said the system was designed to serve Toledoans until the year 2000.

Mr. Rabbitt's job was to keep the new intake cribs clear of debris and to check and maintain valves, gears, and instruments to keep the water flowing westward.

The crib is 100 feet in diameter, 55 feet tall from the surface of the lake, with 20-foot thick reinforced concrete walls. Inside was a set of furnished rooms arranged around a circular hallway, including a kitchen, dining room, living room, bedrooms, and a bathroom. Pictures from 1941 show the couple relaxing in a living room and Mrs. Rabbitt tending an outside garden set on a clean, concrete deck.

Wilhelmina Rabbitt works in the living quarters of the Lake Erie intake crib in August, 1942.

There was only one door to the home, accessed by an iron ladder from the lake.

Another ladder leads to the roof. Like most exterior surfaces at the crib, it is now covered with bird droppings.

The home had its own water treatment system so the Rabbitts could consume the lake water. For the seven years that the Rabbitts lived there, the city annually shipped 75 tons of coal for use each winter.

The rooms now are mostly empty, aside from stacks of detached doors, a dirt-covered sink, and the original cabinetry hanging in what was once a kitchen.

Chuck Campbell, commissioner of water treatment for the city, said the city intends to clean up the inside.

“There was some demo done a few years ago and we have some debris in there that needs to be taken out,” Mr. Campbell said.

A remnant of the heating system — a single rusted radiator — is still there and obsolete chemical treatment tanks stand in the lower level near the center pool of water. The surface of the water last week was calm, as it always is inside, with a layer of green on top.

Peeling paint, crumbling plaster, and a thick layer of dirt are inside the former living area. Outside, the deck and roof where the Rabbitt family relaxed and enjoyed the view is usually occupied by seagulls that have left decades of droppings, fish bones, and their own carcasses.

That iron ladder from the lake, used by the caretaker seven decades ago, is still the only way onto the structure. Boaters are warned by a sign on the building not to come closer than 300 feet and the door is secured by a massive padlock.

Mr. McClure said security employees at the city's low service pump station are alerted by an alarm if the door is opened and they also have a camera on the shore pointed at the structure to watch for trespassers.

This Aug. 14 photo from the city of Toledo shows the barren interior of the water intake crib.

Still, city officials think people have probably entered the building. Scribbled writing is found on one of the living space walls, although officials couldn't be sure the writing wasn't done by past city employees who visit the crib at least once a week to check on equipment.

Also unlike the time Mr. Rabbbitt was there, the city now feeds potassium permanganate into the lake water at the intake crib as a first chemical treatment measure.

Tom Kovacik, who worked for the city for 19½ years, including seven years as utilities director, said some of the Rabbitt family coal was still piled in the structure when he visited the outpost in the 1980s.

“It was ingenious how that intake was built,” Mr. Kovacik said. “The water is all fed by gravity, there is no suction.”

The location was selected in part because of the flow of water from the Detroit River, which offered fresh water from Lake Huron, Mr. Kovacik said.

Algae in the lake was a problem even when Mr. Rabbitt watched over the intake. It apparently wasn't considered dangerous, however.

A 1945 Blade article told Toledo residents that the “evil smell or taste” in tap water then was from algae. George Van Dorp, the water commissioner at the time, told the newspaper it wasn't a health issue and that vegetable matter floated on the lake in beds.

“The cost of treating these beds is too great, so we will have to wait for proper current and wind conditions,” he said. “The condition is prevalent every spring and is nothing to worry about from a health standpoint.”

Mr. Van Dorp again in August, 1949, told the newspaper that an algae-like smell or taste in treated tap water was harmless. He said residents were not getting any of the algae in the water, just its “flavor and odor.”

After last year's algae-induced do-not-drink order, Mr. McClure acknowledged that some debated the location of the intake.

“There was talk about moving it out further in the lake, but this is really the best spot,” he said.

The $9.8 million original price tag to build the crib is a pittance compared to what a new intake would cost today. Mr. Kovacik estimated it would now cost at least $100 million for a similar project.

Contact Ignazio Messina at: imessina@theblade.com or 419-724-6171 or on Twitter @IgnazioMessina.