For chemist, Ohio no Promised Land

Ex-Toledoan sees culture shift in South

2/8/2017

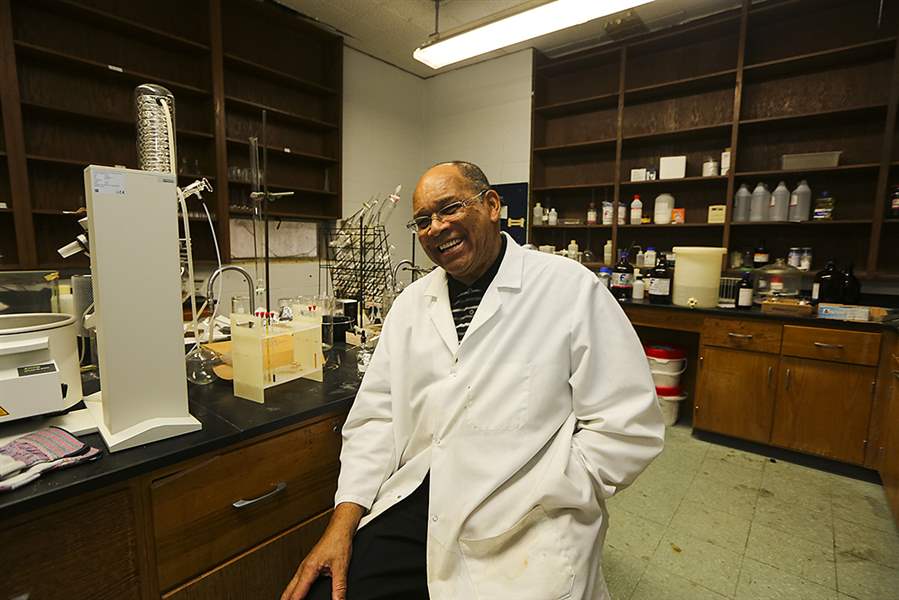

George Armstrong, now a professor and chairman of the chemistry department at Tougaloo College in Jackson, Miss., used to work for Libbey-Owens-Ford Co. in Toledo.

THE BLADE/JETTA FRASER

Buy This Image

JACKSON, Miss. — The passage of years has a peculiar way of drawing the past closer, so that by the time George Armstrong turned 80 his proximity to slavery no longer seemed so far away or long ago.

He grew up with a tale, told by one generation to the next, of his great-grandfather and brother.

George Armstrong, now a professor and chairman of the chemistry department at Tougaloo College in Jackson, Miss., used to work for Libbey-Owens-Ford Co. in Toledo.

Time’s other trick, of blurring the edges of memory, hasn’t softened the harshness of his heritage.

“There’s a story in my family about him and his brother, and I don’t know which one it was. They were sold from their mother as slaves, and she came out and took a piece of bread out of her pocket and gave them a piece of bread and said, ‘Be good boys,’ ” Mr. Armstrong said. “As a kid, it seemed like sort of a ways, but as I look at it, that was my mother’s grandfather.”

In his own life, Mr. Armstrong witnessed segregation fade to integration as he traveled south to north to south again.

A job at General Tire and Rubber Co. brought the research chemist to Akron in the mid-1960s, during the waning years of a migration that sent millions of African-Americans north for work. He later lived in Toledo, and his inventions for Libbey-Owens-Ford Co. produced several patents related to automobile window safety.

In 2002, after working in other places, he returned south to teach chemistry at Tougaloo College near Jackson, Miss.

VIDEO: George Armstrong

He was born in 1936 about 200 miles eastward in rural Monroeville, Ala. — hometown of author Harper Lee. The novelist set To Kill A Mockingbird, about a falsely accused black man, in a 1930s fictional small Alabama town.

Mr. Armstrong grew up in the real version.

“You can probably hardly imagine how oppressive segregation and discrimination against black people [was] in the South,” he said.

His parents shielded him from brutality as much as possible, but hostility — stifling and daily — came up like the scorching Alabama sun.

“It was so ingrained in the culture that you tend not to notice it. You didn’t go to some places. You didn’t do some things,” he said.

The family rented and then purchased land and grew typical southern crops like cotton, corn, peanuts, and vegetables. His parents pulled him out of school to help plant in the spring and harvest in the fall.

ABOUT THE SERIES

African-Americans are returning to the South in record numbers, reshaping a region millions of blacks abandoned during the Great Migration. Reporter Vanessa McCray and photographer Jetta Fraser spent a week driving through Georgia and Mississippi and visiting former Toledoans.

During Black History Month, The Blade tells their stories.

Sunday: Gail Rayford-Ambeau

Monday: Rev. Floyd Rose

Tuesday: Anne Brodie

Coming Thursday: Birdel Jackson

Sunday, Feb. 12: Young, educated blacks are leading the exit south. What can Toledo do to retain these bright minds?

“They equated schooling with being able to survive and help yourself. And, even though they had this strong ... appreciation for schooling they still had to keep me out of school at times to work,” he said.

The Monroeville high school from which he graduated in 1955 was one of about 5,000 black schools built with support from Sears, Roebuck and Co. President Julius Rosenwald. From roughly 1915 to 1935, his foundation helped communities pay for schoolhouse construction throughout the rural South. Alabama alone boasted 389 Rosenwald schools, according to a Nashville architect who has researched the massive building endeavor.

“Even though the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments had occurred, African-Americans, particularly in the South, were very much discriminated against in what was known as separate and what turned out to be unequal education opportunities,” said Michael Hall, of the architecture firm Fanning Howey.

Education played a big part in Mr. Armstrong’s life.

He studied biology and chemistry at Knoxville College, and played on the football team. After he obtained a master’s degree from Atlanta University, General Tire offered him his first chance to live in the North.

“We thought going up north was the Promised Land. I got there, in Akron, and many things were still segregated,” he said.

Among the disappointing discoveries: Black people skated at a roller rink on their own night, and the public school had few black teachers.

He took advantage of a night program and enrolled in 1965 at the University of Akron and received his doctorate in polymer science in 1972. His work as a research chemist took him to labs in several cities. In 1984, he landed in Toledo, where he lived about five years.

George Armstrong, back row second from right, stands with his 1955 Monroeville high school class. It was one of about 5,000 black schools built with support from Sears, Roebuck and Co. President Julius Rosenwald.

His wife, Alfredlene, taught reading at Sherman Elementary. They bought a house in Springfield Township and socialized with a wide circle of black doctors and teachers.

Mr. Armstrong was comfortable, but a recruiter called with another job opportunity. He moved again and again.

As he approached the end of his career, Tougaloo offered him the chance to do what he’d always wanted: Teach at a historically black college like the one where he’d gotten his start.

The move to Mississippi delivered a culture shock greater than any of his previous relocations.

“When I got back here ... white people were nicer than the ones up north,” he said.

One small gesture astonished the man who grew up in the South surrounded by discrimination. He and his wife went out to eat, and a young, white couple gave the Armstrongs their seats.

“I had no idea that Mississippi had changed that much,” he said.

The scientist in him hasn’t.

The 80-year-old keeps his white lab coat within reach, and his enthusiasm bubbles over when he talks about his current cancer-drug research.

Mr. Armstrong also is contemplating one more move.

It’s a flicker of an idea, but it flashes through his mind: Teach a couple more years and then return to land he owns in Alabama.

Contact Vanessa McCray at: vmccray@theblade.com or 419-724-6065, or on Twitter @vanmccray.