Time for change? Schools wrestle with Native American nicknames

1/5/2018

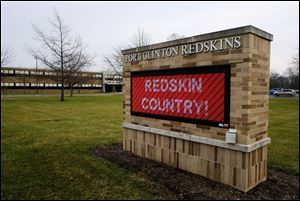

A sign outside of Port Clinton High School features the school nickname of Redskins. Port Clinton is one of the 85 schools in Ohio with an Indian-themed nickname.

THE BLADE/JEREMY WADSWORTH

Buy This Image

Redskin, labeled as disparaging and offensive in the dictionary, is defined as a contemptuous term used to refer to a North American Indian.

Flip backward a few hundred pages and you encounter the N’s, and the English language’s most ugly word. It too is labeled as offensive and defined as an insulting and contemptuous term for a black person.

That begs the question why, in 2018, are high schools in the state of Ohio still using a derogatory slang word as a nickname?

Is it tradition, or is it ignorance?

A sign outside of Port Clinton High School features the school nickname of Redskins. Port Clinton is one of the 85 schools in Ohio with an Indian-themed nickname.

Eighty-five Ohio high schools have a Native American nickname, including 12 “Redskins” and five “Redmen.” The state ranks No. 1 in high schools with Indian nicknames, according to the American Indian Sports Team Mascots website.

In The Blade’s coverage area, there are the Fostoria Redmen, Port Clinton Redskins, Bellevue Redmen, Waite Indians, Tiffin Calvert Senecas, Arcadia Redskins, Shawnee Indians, and Wauseon Indians.

Several state departments of education have taken a stance against Indian nicknames, including Michigan’s, but Ohio has avoided the polarizing topic.

California Gov. Jerry Brown signed a law that prohibits schools from using the term “Redskins” and the state of Oregon Board of Education banned the use of all Native American nicknames, with the exception of Warriors, or risk losing public funding.

The Ohio High School Athletic Association has not discussed getting involved, with spokesman Tim Stried saying, “Mascot names and logos are entirely up to each school.”

In an age in which the viability of the NFL’s Washington Redskins name has been debated in court and Native Americans have annually protested against the Cleveland Indians’ use of its red-faced, big-toothed Chief Wahoo logo, high school communities are facing similar questions.

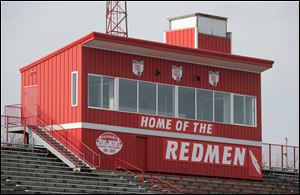

The fieldhouse at Bellevue High School features an Indian logo and the school's Redmen nickname.

Friday nights in Ohio during the fall are sacred days. Entire communities gather at the local high school football stadium to take part in an event that’s ingrained into the state’s ethos. Football is king.

On the shores of Lake Erie, Port Clinton is a classic lakefront town with a cutesy downtown that serves great perch and walleye. It’s also the home of the Redskins, a nickname that’s been attached to Port Clinton High School for decades. And good luck to those who try to stir change. The team’s helmets might say “PC,” but it does not stand for politically correct.

When the idea of changing the Redskin nickname was broached with superintendent Patrick Adkins on the basis that it would be viewed positively by the general public, he disagreed.

“There's not going to be good publicity coming out of it from our community,” Adkins said. “This is a great tradition and a great sense of pride to this community. It’d be different if we had a lot of people calling this community pushing for this change, but it is not happening.

“The Redskin name, we understand what it means to a lot of people, and we are sensitive to how it can be viewed. For us, it certainly isn’t viewed that way. It’s a sense of pride. It’s been part of this community for an awfully long time. It’s something this community is proud of.”

Adkins said that the board of education has discussed the use of the name, but said that there would be “significant opposition” in the community to changing it.

Debate over the origin of “redskin” has raged for years. What can’t be disputed is that Webster’s Dictionary began using “contemptuous” to define the term in 1898.

The press box at the Bellevue High School's football field. The Redmen are in the Sandusky Bay Conference.

The stance from many Native Americans is quite simple. They are not mascots, and they believe teams with Indian nicknames mock their entire race.

“First of all, [people who don’t oppose Indian nicknames] don't know any of their history. They haven’t been taught anything about Native Americans,” said Clyde Bellecourt, a Native American and one of the leading voices against Indian nicknames. “They have what I call the John Wayne frontier mentality — the only good Indian is a dead Indian.”

Bellecourt, of Minnesota, is a coordinator of the National Coalition on Racism in Sports and the Media, which has urged professional franchises, colleges, and high schools to change nicknames. Bellecourt crisscrosses the country giving speeches on why the nicknames are offensive.

Dozens of universities have changed their nicknames in recent decades after outside pressure and at the urging of the NCAA, which voted to impose sanctions against schools using “hostile or abusive” nicknames in 2005. The University of North Dakota was the most publicized after an uproar among the university’s alumni and influential boosters. The case went through court, and after not using a nickname for several years, North Dakota changed from the “Fighting Sioux” to the “Fighting Hawks” in 2015.

Several schools, including Illinois, Florida State, and Central Michigan, received permission from tribes to continue using their nickname, though Illinois retired its mascot, Chief Illiniwek.

Twenty-three miles south of Port Clinton, another small Ohio town reveres high school football. Bellevue, population 7,973, is home of the Bellevue High School Redmen. And like Port Clinton, there’s been no push to change the school’s nickname.

But there’s a level of awareness and respect from ninth-year superintendent Kim Schubert. The district has minimized the use of its longtime logo featuring a Native American wearing a headdress and instead has gone to a “B,” and the girls teams now are known as the Lady Red.

“We’re very sensitive to the issue, and I know it’s a conversation that goes on around the country,” Schubert said. “It’s not that we have refused to discuss it, we just haven't been approached about it. We’ve taken a look at our logo and the Indian is not something that we predominately use in any of our advertising. We have gone to using our ‘B’ for Bellevue.

“I changed our logo a few years ago. When we do use the Indian, we use it in a respectful manner. We do not have a mascot dress up. It is a part of who we are and it is our school nickname, but we use it respectfully.”

Bellevue alumnus Megan Tobin, who graduated in 2006, did a turnabout on the nickname conversation after she witnessed a sacred Chanupa ceremony on the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation in North Dakota. In high school, Tobin joined her friends wearing war paint and dressing up with feathers and headdresses for Bellevue football games.

“I understand now that I was blinded by my privilege like so many others in this community,” she said. “It wasn’t until September of last year that my eyes were opened and my entire viewpoint was changed, and it all happened in one discussion. It was an honor to be welcomed to witness [the Chanupa] ceremony as an outsider, and it will be something I never forget.”

In November, 2015, a Facebook discussion on a Bellevue page turned hostile when someone posted a video of a Native American talking about the negative effects of Indian nicknames.

“Community backlash is a very real thing, especially in a town as small as Bellevue. Things can become personal and threatening in a blink of an eye,” said Tobin, who opted against starting a petition last year to change the Redmen name for fear of retribution. “I always regretted the decision I made not to petition for the name change, and that’s why I decided to do this interview. If I can educate and change just a few people’s minds on this topic, then they can educate others and possibly change their minds, and so on. It could be a snowball effect of awareness and change, something that is desperately needed in the town of Bellevue.”

The family of a 16-year-old black student filed a lawsuit against the Bellevue School District in 2014, alleging that their daughter experienced consistent racist and discriminatory treatment from students and teachers. The district settled the lawsuit for $110,000, though it claims it was not an admission of guilt.

Following the settlement, a Bellevue student made a Facebook post disparaging the girl through the use of racial slurs and jokes about her family being on welfare.

Every major organization that represents Native Americans has called for the Washington Redskins to change their name. However, there are Native Americans who aren’t opposed to the nickname. One of them was Ronald Everett, a now deceased spiritual leader of the Red Cliff Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians who graduated from Port Clinton in 1945.

Everett’s only qualm with Port Clinton was with students who dressed up as Native Americans and mimicked dances. He saw it as a sign of disrespect, and Adkins has discouraged students from doing so.

“If they had enough guts, they would have an audience and discuss the issue,” Bellecourt said.

Elsewhere in northwest Ohio, Tiffin Calvert stopped using a headdress on its mascot after researching the Seneca Indians and learning that they did not wear headdresses.

Arcadia High School, known as the Redskins, is located in Hancock County, 10 miles northeast of Findlay. The rural community has a population of less than 600 people, and the town is 0.58 square miles.

Bruce Kidder is in his third year as the district’s superintendent and said the only person who’s approached him about a name change was a college student working on a project.

“Being a small farming community, some of these people have been redskins for four or five generations,” Kidder said. “It would be interesting to see what it would cost to change over. It would be fairly expensive. We’ve got uniforms, templates, carvings, letterhead. It would have to be a serious financial commitment for a small rural district. I don’t know any superintendent in Ohio who would unilaterally make that move.”

In 2015, athletics gear supplier Adidas announced an initiative encouraging high schools nationwide to drop Native American nicknames. The company provided financial support to schools to ensure the cost was not prohibitive. The schools had access to Adidas’ design team to collaborate on uniforms and new logos for their athletics teams, a move applauded by then-President Barack Obama. No schools in Ohio have taken part.

Arcadia’s logo is cartoonish: a red-skinned Indian, with deep creases in the face, wearing feathers.

“The red-skinned caricatures that we use as mascots perpetuate negative stereotypes against Native Americans, dehumanizing them in the process,” Tobin said. “It takes away from the real issues that are plaguing their communities, such as treaty violations, racism, high rates of hate crimes and suicides, and the alarming number of missing and murdered Indigenous women.

“Decades of social science research proves that these derogatory sports mascots have serious psychological, social and, cultural consequences to the Native American people, especially the youth in their communities.”

Contact Kyle Rowland at krowland@theblade.com, 419-724-6110, or on Twitter @KyleRowland.