UT lauds 1st black professor’s work, spirit

40-year veteran taught many lessons, but learned some too

2/24/2014

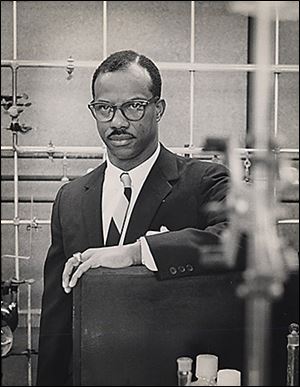

In 1958, Lancelot C.A. Thompson, the first black professor at what was then Toledo University, was well-versed in the hard lessons of racial discrimination.

The Blade/Andy Morrison

Buy This Image

In 1958, Lancelot C.A. Thompson, the first black professor at what was then Toledo University, was well-versed in the hard lessons of racial discrimination.

He was the first black professor hired by the University of Toledo.

But chemistry instructor Lancelot C.A. Thompson, who was 32 at the time in 1958, initially had a hard time convincing some people of that.

To get to work, he would drive through the area of Westwood Avenue and Dorr Street, which was then considered to be a white neighborhood.

“The police would pull me over and accuse me of failing to stop at the stop sign ..,” a now 88-year-old Mr. Thompson recalls. ‘What are you doing over here?’ the police would ask me.

“When I told them I was faculty at the university, they would call me a liar and give me a ticket.”

The recognition is long overdue and well-deservied. Mr. Thompson was a pioneer who paved the way for other black professionals at the University of Toledo, longtime friend John C. Moore, 77, said of Mr. Thompson.

When he arrived on campus at the then-Toledo University, school security would try to stop him from entering the faculty parking lot.

Sometimes they would threaten him; other times they would mock him for claiming that he, a black man, was a professor.

“They tried to stop me from parking in the lot,” Mr. Thompson said. “But I did anyways.”

Fifty-five years later, Mr. Thompson, who retired from the University of Toledo in 1998 after 40 years, received a much warmer greeting when he returned to campus last week so that school officials could honor him. Officials unveiled the Lancelot C.A. Thompson Meeting Room in Student Union Room 2592 during a short ceremony.

“Over the years, Lance has been an adviser, a mentor, and most of all, a friend to many of our student-athletes,” said Mike O’Brien, the University of Toledo’s athletic director. Several school officials took turns praising Mr. Thompson’s contributions to the school. More than 100 people attended the event, including students, school officials, Mr. Thompson, his family, and friends.

Longtime friend John C. Moore, 77, said the recognition is long overdue and well-deservied. Mr. Thompson was a pioneer who paved the way for other black professionals at the University of Toledo, he said.

“He is such an intelligent gentleman who is really concerned about the fate of his fellow man,” said Mr. Moore, who is a retired vice president of university development at Bowling Green State University. “He’s very educated and still wants to learn something new every day.

“He’s fearless, and he makes it look so easy.”

Although naming a room in his honor is a nice gesture, some community leaders such as Mr. Moore would like school officials to take the next step and name the Student Union after Mr. Thompson.

For 22 years, during most of which he was vice president for student affairs, Mr. Thompson’s office was housed in the Student Union.

“Why do the black men always get a room?” asked community activist Bernard “Pete” Culp, a member of the Toledo Community Coalition, which is dedicated to raising public awareness about racial issues. “They ought to name the Student Union after him.”

When asked about the honor, Mr. Thompson laughed and quoted a few words from a letter he recently received from a friend: “It was a long time coming.”

Meghan Cunningham, a spokesman for the university, said naming a campus building or room after someone is not often done and is reserved for people who’ve made extraordinary contributions to the school. That doesn’t always mean financial contributions, she said.

Mr. Thompson, whose parents were teachers, was born and raised in Jamaica. He was a 24-year-old high school teacher when he received track scholarship offers from Morgan State University in Maryland and Tennessee State University.

“Many people in Jamaica, they told me, go to Morgan State; they will lynch you in Tennessee,” said Mr. Thompson, who pointed out that Morgan State University is a historically black college.

An accomplished athlete, Mr. Thompson competed in the broad jump and 400-sprint relay during the 1946 Pan American Games held in Barranquilla, Colombia, and again during the games held in Guatemala. Both times he took second-place honors in the competition.

Lancelot C.A. Thompson, in his research lab in 1965, was born in Jamaica. At 24 years of age, he arrived in America and immediately was introduced to racism.

At 24, he boarded a plane for Morgan State University. It didn’t take long for Mr. Thompson to be introduced to American racism and discrimination.

“Jamaica is a biracial country, so we didn’t have those problems,” he said. “In Jamaica, it’s more about class issues.

“The first time I got to an airport I saw no black people, so I started to look for a place to sit down. A black janitor came over and told me I wasn’t allowed to sit in that section. He sent me to another part of the airport where other black people were. That was my first experience in America.”

The trip got worse. He boarded a train to Baltimore, but before he could sit down he was dragged and deposited in the “black coach” section of the train.

“Everybody in there were black southerners,” he said. “I didn’t understand a single word they said.”

He earned a bachelor of science degree in chemistry from Morgan State in 1952 and a doctorate in physics and inorganic chemistry from Wayne State University in 1955.

He returned to Jamaica with the goal of “trying to revolutionize the way we were teaching chemistry,” he said. The school books in Jamaica were old and outdated, and it was difficult to get the “powers-that-be” to understand how much chemistry had changed over the years, he said.

Mr. Thompson returned to the United States in 1957 and attended a job fair in New York. He applied for and received numerous interview requests. He soon realized that was because potential employers didn’t know he was black.

“A guy from Alabama, when he saw me, he turned so red I thought he was going to have a heart attack,” Mr. Thompson said. “ ‘You know where Alabama is, don’t you?’ the man asked me. ‘Yes sir,’ I told him.

‘You know we probably don’t want you,’ he said. ‘I probably don’t want to go,’ I said.”

When Mr. Thompson applied for the University of Toledo job, he included a photo so there would be no surprise that he was black. The person who interviewed and hired him, Jerome Kloucek, dean of the arts college, never mentioned race, Mr. Thompson recalls.

“Some of the faculty was a little uncomfortable,” Mr. Thompson admits. “But I was comfortable. I was used to being around white people.”

Lancelot C.A. Thompson reflects at the Toledo Club on his tenure at UT. He was recently honored at UT with a room named after him. He retired in 1998.

Mr. Thompson did more than teach chemistry, school officials said. He created the school’s first track team. He started the annual Aspiring Minorities Youth Conference.

In 1964, he was voted the school’s Outstanding Teacher and served as assistant dean for undergraduate study in the college of arts and sciences from 1964-66.

Mr. Thompson became dean of student services from 1966-68, before being promoted to vice president of student affairs, a position he held until retiring in 1988. He retired as a teacher in 1998.

Mentoring youths, especially black youths, was always a priority, he said.

“Being the only black faculty at the university for four years, I had to be a mentor,” he said. “There was nobody else for them.

“It didn’t matter if it was a black, white, Hispanic, or Asian student, my job was to teach and mentor all students.”

He admits to being extra hard on black students.

“Oh yes, I was hard on them,” Mr. Thompson said. “I made sure they did the work. I was harder on them than the other students because I knew they had to be a little better than the whites to get the job. You had to be prepared.”

Contact Federico Martinez at: fmartinez@theblade.com or 419-724-6154.