Seeing big problem with dropouts, TPS makes it personal

Teachers, district zero in on individuals, raise expectations

1/31/2016

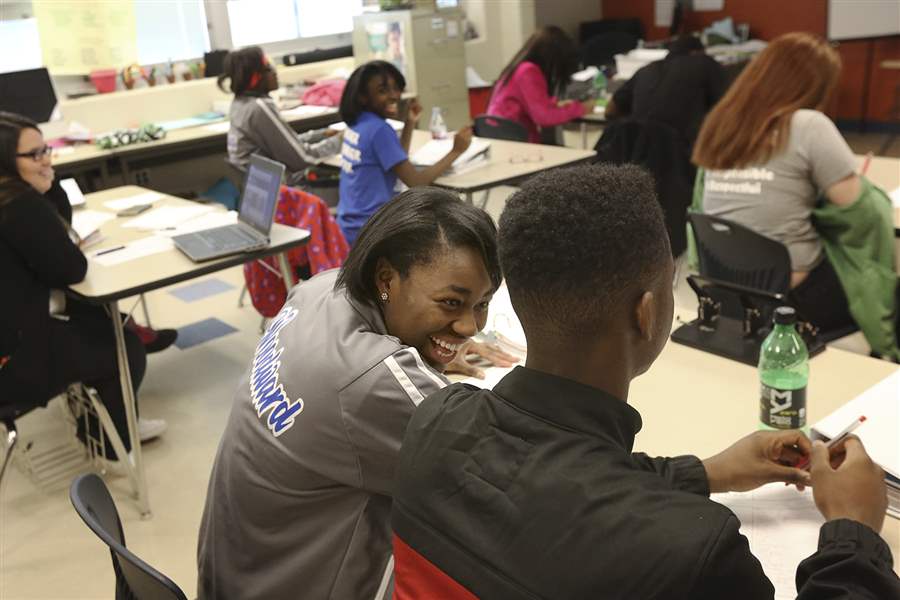

Candace Spencer, 16, center, jokes with Eric Hodge, 15, during Woodward’s college prep class.

THE BLADE/KATIE RAUSCH

Buy This Image

Teacher Ann Koch-West instructs her college prep class for freshmen and sophomores.

During a recent morning meeting, a group of Scott High School educators talked about how to help one struggling student.

The girl failed three first-semester classes, and the teachers, counselor, principal, and data coordinator who huddled together were brainstorming the best way to get her back on track.

They looked at her grades and pulled up her schedule. The teachers, several of whom had her in their classes, shared what they knew.

She’s social, one teacher remarked. Easily distracted by classmates.

Could shuffling her schedule solve the problem? The group decided it was worth a try, and before moving on to discuss the next student in an alphabetized list they had made a plan to meet with her and discuss a switch.

Woodward sophomores Alejandra Jimenez, 16, bottom left, and Reana Barboza, 15, lean against one another as they each write during a college prep class Jan. 27.

This kind of drop-out prevention — exhaustive, time-consuming, and personal — is one way Toledo Public Schools hopes to boost languishing graduation rates.

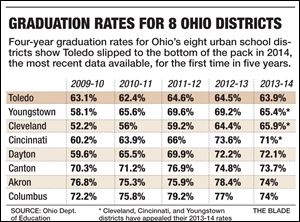

Just 63.9 percent of the 2014 class graduated within four years.

The newest data from the Ohio Department of Education, released earlier this month, places Toledo as the second-worst performer among more than 600 public school districts. Only Mansfield schools has a lower four-year graduation rate for its class of 2014.

Toledo’s rate has changed little since 2009-10, when 63.1 percent of its students graduated in four years.

That stagnant graduation rate dropped Toledo to the bottom of the heap among the state’s eight major urban school districts.

For the first time in at least five years, Toledo lags behind Cleveland’s embattled school system.

“We slipped behind Cleveland, and we have not historically been there,” said Jim Gault, TPS’ chief academic officer. “Initiatives in our high schools we needed to start earlier ... and with that it’s going to be a delayed response to see the fruit of our labor.”

Though some urban districts are improving, Superintendent Romules Durant pointed out they’re all still considered to be failing.

“Let’s be real,” he said: State report cards gave all eight urban districts an “F” for their 2014 four-year graduation rates.

TPS hasn’t made gains while other districts have because it didn’t provide enough interventions and support for high schoolers, said Mr. Durant, who became superintendent in 2013.

The district has concentrated on reforming early and elementary education. In 2011-2012, it reorganized elementary and middle schools into a K-8 model that he said created a “nourishing and caring environment.” He said suspensions are down, parental involvement is up, and other promising signs show that effort will help students succeed in high school.

“You have to start on the front end,” he said.

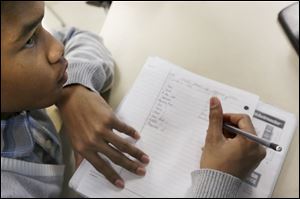

Willie Mullins, 15, left, and Myah Robinson, 15, learn how to take better notes. Select TPS schools offer the college prep program Advancement Via Individual Determination.

New programs

In more recent years, work has expanded to develop high school programs the district hopes will increase graduation rates.

Scott is the first TPS high school to fully implement an early-warning system — a nationally recognized approach that calls for teachers and other staff to monitor attendance, grades, and behavior, pinpoint issues, and assign a specific level of intervention to head off problems that could cause a child to drop out. Teams at Scott routinely review data for all freshmen and those sophomores at-risk of falling behind.

The effort began during the 2012-13 school year, and the district credits it with increasing the number of ninth graders who have earned enough credits to stay on-track after their first semester. That first year, 66 percent of freshmen were on pace to graduate after the first semester; this year 75 percent are.

The district plans to expand the system to other high schools. TPS is pairing that work with a program launched last school year at Toledo’s six comprehensive high schools that clusters freshmen together with a group of teachers to ease the transition into high school. Officials also tout a college-readiness program at several high schools and elementaries because they say it’s not enough just to graduate; students also need to be prepared for the next step.

“We do know that if we can get them to their sophomore year the chance of them dropping out is much less. So the freshman year is really a big year for them,” said Lorie Pietrasz, a special education teacher at Woodward High School who works with the cluster program.

The district’s efforts to create a small-feeling, friendly atmosphere seem to be working, at least for some high schoolers.

Candace Spencer, 16, center, jokes with Eric Hodge, 15, during Woodward’s college prep class.

Woodward sophomore Alejandra Jimenez said sometimes students quit school because of family problems or because they’re hanging around the wrong crowd. But she felt welcomed by Woodward’s college-prep program and has a warm relationship with a teacher whom she and her classmates call “mom.”

“It’s like another family,” she said. “They are always there to support you.”

Statewide numbers

The statewide, four-year graduation rate remained at 82.2 percent for the classes of 2013 and 2014, up slightly from the 2010 rate of 78 percent.

Ohio’s eight urban districts are all below that mark, and all have high percentages of economically disadvantaged students. Research has long shown a link between low graduation rates and high poverty numbers.

The state reported 78.4 percent of TPS students enrolled in the 2013-14 school year were economically disadvantaged. Other districts, such as Cleveland, report even higher numbers.

A recent analysis by Howard Fleeter, a research consultant with the nonprofit organization Ohio Education Policy Institute, found that the average four-year graduation rates of districts with more than 70 percent economically disadvantaged students fell at least 8 percentage points below the statewide average.

Poorer students are more likely to lack proper nutrition, change schools and districts more often, and aren’t as prepared when they start kindergarten, he said.

Despite such challenges, some poor districts are finding ways to lift graduation rates.

“It’s not like Cleveland should be doing cartwheels about this, but at least Cleveland is moving in the right direction,” Mr. Fleeter said.

Tracking students

How Ohio measures graduation rates changed drastically starting with the class of 2010, making historical comparisons difficult.

Previous calculations likely inflated graduation rates; Toledo’s 2008-2009 graduation rate was nearly 84 percent.

The new reporting model tracks individual students using unique identification numbers from their freshman year to determine if they graduated on time, moved to a different school, or dropped out.

That four-year longitudinal graduation rate caused many districts’ graduation rates to drop precipitously.

District officials say it’s now key to keep tabs on students who leave their schools for another so that such moves are recorded as transfers and not drop outs. TPS needs to do better job of it, Mr. Gault said.

The high school cluster concept fosters relationships among teachers, students, and parents and will help the district better track students, Mr. Durant said.

Cleveland schools has combined diligent data tracking with academic initiatives to increase its four-year graduation rates by nearly 14 percent since 2010. The district leaned on existing staff — including counselors and principals — to regularly go through student lists and account for each child.

They’ll show up in person to obtain records from other schools when needed, said Michelle Pierre-Farid, Cleveland’s chief academic officer.

The district recently appealed to the state numerous times over the status of just a handful of students. Correcting that data should nudge the district’s class of 2014 graduation rate up by one-tenth of a percentage point, enough to lift Cleveland’s rate to an even 66 percent.

Minuscule, yes, but Cleveland officials care about it, Ms. Pierre-Farid said.

For a district that, like Toledo, has a significant number of students who move around, such perseverance has paid off. Cleveland typically cleans up its rolls by up to 60 students a year, she said.

“I don’t think anything that we are doing is like rocket science. I think it is being very dogged about our graduation rates,” she said.

Cleveland’s data work is just one of its approaches to boosting graduation rates.

The district hired academic intervention teachers, started using an online credit recovery program to help students make up failed courses, began mailing to students’ homes reports that track progress toward graduation, and added new programs to engage students, said Ms. Pierre-Farid.

By 2017-18, Cleveland aims for a 71 percent graduation rate.

Sophomore Richard Dixon, 15, listens to his teacher Ann Koch-West.

Clusters

On their first day of high school, Woodward’s freshmen got a glimpse of their own graduations.

Teachers in the cluster program wanted them to know what that achievement would look like, sound like, feel like. So they held a mock graduation.

A speaker gave a commencement address. “Pomp and Circumstance” played. Principal Jack Renz handed out diplomas — notes written by the previous freshman class on how to succeed.

Students signed a Class of 2019 banner and promised they would graduate.

Teachers hope such ceremonial steps will cement the importance of getting a diploma.

“One of the things we found out last year was a lot of our students do not have the expectation to graduate — that it was kind of just accepted in their homes or by themselves that graduation would be like a plus,” said Ms. Pietrasz, the special education teacher.

District officials cite the cluster concept as the reason more freshmen are passing core classes.

While 66 percent of Woodward freshmen passed world studies in 2013, 87 percent passed last semester. At Scott, only 49 percent passed physical science in 2013, but 73 percent of the current class passed, according to TPS data. While those are among the most dramatic gains, all six high schools have seen improvements.

The district is implementing an online credit recovery system so students can quickly catch up if they fall behind.

This year, the cluster concept expanded to include lower-performing sophomores with the intention that they would share the same teachers and travel together from class to class as a pack.

While the district strives to step in sooner to help struggling students, it also wants to better prepare students in the “academic middle” — those with a 2.5 to 3.0 grade point average who often become the first generation of college-goers in their families, said Jennifer Lawless, director of strategic initiatives.

The college prep program Advancement Via Individual Determination, or AVID, is offered in select TPS high schools and elementaries. High schoolers take an elective course in which they learn vocabulary, practice writing, and improve their note-taking and organizational skills.

Ask Alejandra or several of her Woodward classmates in the program if they plan to graduate from high school and all respond with an emphatic affirmative.

Sophomore Reana Barboza said the program improved her writing and kept her from procrastinating in other subjects.

The college-prep students acknowledged some have a bleak perception of their high school, which graduated just 43.7 percent of its 2014 class in four years. But, Woodward has offered them good opportunities.

“When people talk about Woodward it’s always like, ‘Oh, people dropping out. Oh, girls getting pregnant and all this,’ and that’s not really how it is here,” said sophomore Miranda Dominguez.

TPS officials hope the steps they’re taking now will lead to increased graduation rates. Mr. Durant wants to reach the 80th percentile within five years.

“We are not happy with where our graduation rates are. We are excited about where the possibility is,” Mr. Gault said.

Staff writer Nolan Rosenkrans contributed to this report.

Contact Vanessa McCray at: vmccray@theblade.com or 419-724-6065, or on Twitter @vanmccray.