Video rekindles debate about police treatment of blacks

Woman allegedly hanged herself in jail after tense arrest

7/23/2015

In this July 10, 2015, frame from dashcam video provided by the Texas Department of Public Safety, trooper Brian Encinia reaches into the car to arrest Sandra Bland after she became combative during a routine traffic stop in Waller County, Texas. Bland was taken to the Waller County Jail that day and was found dead in her cell on July 13. (Texas Department of Public Safety via AP)

ASSOCIATED PRESS

Texas Department of Public Safety, trooper Brian Encinia arrests Sandra Bland after she became combative during a routine traffic stop.

HEMPSTEAD, Texas — When Sandra Bland refused to put out her cigarette, the police officer flung open her car door and tried dragging her out of the vehicle. She asked at least four times why she was being arrested and got no answer. When she told him she had epilepsy, he shouted, “Good!”

The tense dashcam video of Bland, a 28-year-old black woman, getting pulled over by a white Texas state trooper for not signaling a lane change renewed the national debate Wednesday over how police treat blacks and outraged some critics of law enforcement who saw a motorist who was squarely within her rights.

Bland’s traffic stop drew special attention because she was found dead in her jail cell three days later, and family and supporters continue to dispute that she hanged herself with a plastic garbage bag, as authorities have concluded.

The video of the traffic stop in rural Waller County drew more than 1.2.million views on YouTube, less than a day after the Department of Public Safety made the footage public. But a range of experts, including former law enforcement officials and civil rights attorneys, say the video is not a clear-cut case of an officer overstepping his authority in the face of an agitated motorist.

“Believe it or not, sometimes you can’t just look at the video and tell,” said Phillip Lyons, a former police officer and current dean of the College of Criminal Justice at Sam Houston State University in Huntsville, Texas.

The state trooper pulled over Bland on July 10, when she was at Prairie View A&M University, a historically black college, to interview for a job at her alma mater.

The traffic stop swiftly escalates into a shouting match after Encinia tells Bland she seems “irritated” and asks her to put out her cigarette. When Bland protests — “I’m in my car, why do I have to put out my cigarette?” — Encinia orders her on the street and opens the door to drag her out when she doesn’t comply.

Simply ignoring instructions to stop smoking typically isn’t sufficient grounds for police to demand someone to get out of their car. But officers also have wide discretion to take control of a scene.

Lyons said he saw nothing that was “clearly inappropriate or unnecessary” about the request, but the legal threshold rises when an officer determines that a driver must be physically removed from a vehicle.

The justification for using force is generally supposed to be proportional to the circumstances. Bland is asked more than a dozen times to get out before Encina, by then visibly annoyed at her refusal, reaches into the car.

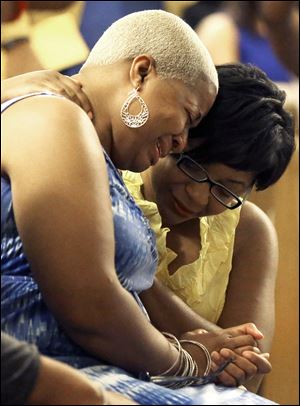

Shante Needham, left, and Sharon Cooper comfort one another at a memorial service for their sister Sandra Bland at Prairie View A&M University, Tuesday, in Prairie View, Texas.

“We don’t observe anything that would suggest there was a legitimate law enforcement reason to get out of the car. It seems to be just an issue of asserting his authority,” said Rebecca Robertson, the legal and policy director for the American Civil Liberties Union of Texas.

But at the same time, Robertson said, if an officer instructs you to get out, “you have to get out of the car.”

Bland ultimately steps out of her car on her own after the trooper says, “I will light you up,” an apparent threat to use the stun gun he had drawn.

The speed with which Bland was threatened seems to run counter to best practices described in a 2011 Justice Department report about Tasers. The report cited a police survey in which most departments said they allow only “soft tactics” against someone who refuses to comply but doesn’t physically resist.

Bland also tried recording the encounter on her phone before being told to stop, which experts say is a command police can rightfully make if it interferes with their duties.

To some experts who watched the video, it would have been in the interests of both Bland and trooper Brian Encinia to simply remain calm.

And even though Bland, who talked about police brutality on social media before her arrest, seemed to be aware of her rights, the officer’s instructions may not have crossed a line, even if his behavior did.

The director of the Department of Public Safety, Steve McCraw, has said Encinia violated internal policies of professionalism and courtesy, but he has not said the trooper acted outside the bounds of the law. Encinia has been placed on administrative leave for violating unspecified police procedures and DPS policy.

“His whole demeanor, his vocabulary, the way that he spoke to this motorist,” said Vernon Herron, a senior policy analyst with the Center for Health and Homeland Security at The University of Maryland. “I just think it added to the fact that she became combative.”

When the confrontation moves off-camera onto the sidewalk, Bland is heard screaming that the trooper is about to break her wrists as she is handcuffed. Bland was arrested for assault on a public servant. In an arrest affidavit, the trooper wrote that Bland had swung her elbows at him and kicked him in the shin.