Harsh weather has the ability to reassure us

This winter can appeal to innate sense of normalcy

2/23/2014

A man makes his way through the parking lot of Gibsonburg High School after the Ottawa Hills basketball game on Feb. 4 in Gibsonburg, Ohio.

THE BLADE

Buy This Image

A man makes his way through the parking lot of Gibsonburg High School after the Ottawa Hills basketball game on Feb. 4 in Gibsonburg, Ohio.

You’ve endured more backaches shoveling snow this winter than you can remember.

You’ve been annoyed by all of the yakety yak about the polar vortex, some bizarre thing in the upper Arctic atmosphere that means nothing to you other than it brings unmerciful, bone-crushing wind chills. You go batty when the media remind you how the deep, subzero temperatures could put you in the hospital — or 6 feet below ground — faster than you can imagine.

It’s been a heck of a winter, one in which you’ve felt like a prisoner of nature, whether you were scampering between stores for emergency supplies on the eve of the next storm, scurrying around like a rat seeking warmth between heated buildings and heated automobiles, or groaning — as you probably are now — about the prospect of another hard freeze next week.

You are — to put it mildly — fed up.

Or are you?

Strange as it may sound, some psychologists believe there’s a large number of us who may actually be diggin’ this winter, whether we realize it or not.

Deep down inside, the theory goes, the harsh winter being experienced by the Great Lakes region and the East Coast has been having a calming effect on the collective psyche of residents there, taking them back to what they associated with winters of their childhoods — far unlike the massive, all-day thunderstorms and lightning that moved through the Toledo area on Thursday, summerlike events that, at one time, would have been unthinkable for February and now just seem a little weird.

First, a little perspective.

Nobody’s suggesting we actually enjoy driving through a seemingly endless barrage of freezing rain, hail, sleet, and snow for weeks at a time. Nobody’s suggesting it’s healthy to get sick with worry, praying we don’t lose control of our cars or trucks while slip-sliding on icy, pothole-peppered roads and wondering if our limp, broken bodies will end up in a ditch in the middle of nowhere, smothered by a mini avalanche until spring.

No, that’s not what they’re talking about.

They’re talking about how weather — even occasional bouts with harsh weather — can appeal to our innate sense of normalcy, something that may be in the process of being redefined or thrown out of whack by climate change.

Trucks slowly move north on I-75 near Summit Street in Erie Township, Michigan, as snow hammers the area on Feb. 5. Ice, snow, wind, and potholes have made driving a white-knuckle event.

Return to normal?

Alan Stewart, a University of Georgia associate psychology professor who also lectures on geography and atmospheric sciences, said those of us who grew up with “normal” winters yearn for what we were conditioned to expect as youths.

This winter feels more right to us, Mr. Stewart said.

“Depending on where the person is, we do get attached to different types of weather and like to have variety,” Mr. Stewart, who holds a PhD in psychology, said. “When the weather pattern doesn’t happen or it goes absent for several seasons, I think it does affect people.”

Those who grow up in the North associate cold weather with Christmas and New Year’s Day, for example.

They may not expect snow every Christmas. But it feels weird to them if it’s too warm and balmy, he said.

Weather extremes can be trying, but there’s also “sort of a joyous or wistful experience” coming back to something that feels more familiar, Mr. Stewart said.

“To see something more like normal, it can soothe the psyche on several levels,” he said.

There’s also something gratifying about being battle-tested and being able to talk about it, he said.

“People like to socially compare about the weather they’ve lived through,” Mr. Stewart said.

Seasonal blahs

Psychology’s a tricky thing, though.

While there can be commonalities among people in various regions, there are many distinctions within each group of people.

Winter’s not a joyous or wistful experience for people who suffer from what’s known as seasonal affective disorder, or SAD — a fancy term for seasonal depression.

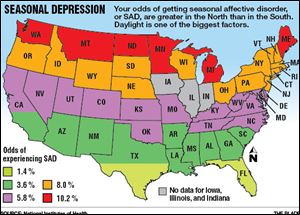

Research shows the higher the latitude, the higher the prevalence.

Seasonal depression is virtually nonexistent by the equator, whereas there is a high rate of it in Greenland and other parts of the Arctic. Greenland has one of the world’s highest rates of teenage suicide, much of which is believed to be related to weeks of 24-hour winter darkness.

Patterns of seasonal depression are well-established in the United States.

According to data published in 1990 by the National Institutes of Health, the odds of getting seasonal depression range from 1.4 percent if you grew up in south Texas or Florida to 10.2 percent if you grew up in Michigan, Minnesota, North Dakota, or other northerly states. The rate of incidence among Ohioans is about 8 percent.

The study is old, but it was well done and the questionnaire used for the phone interviews is still used today, so there’s been no reason to update it, said Kathryn Roecklein, a University of Pittsburgh assistant professor of psychology.

She said about 40 percent of seasonal depression is believed to be genetic.

“So you’re not going to change a person’s inborn tendency,” she said. “One thing we don’t want to do is trivialize the experience of someone with a clinical disorder.”

The biggest factor is seasonal availability to light, Ms. Roecklein said. Many people who suffer from seasonal depression use desktop devices known as “light boxes” for therapy to help curb some of the effects of their condition.

Ms. Roecklein has a PhD in psychology and is affiliated with the Center for the Neural Basis of Cognition jointly operated by Pitt and Carnegie Mellon University.

She calls light therapy a “first line of treatment for SAD.”

“It’s very effective,” Ms. Roecklein said.

The amount and type of exposure to artificial light is prescribed by psychologists, who warn of possible side-effects if not followed correctly.

Lighting the way

Although winter is a rough time for people with seasonal depression, there’s some belief — though not a lot of research in this area yet — that they could benefit slightly from more snow and ice if they live in areas historically prone to them.

Snow and ice reflect light, thereby making more light available to them during what is normally a cloudy, overcast time of year in the North.

“It is plausible that when you have a snowpack, that limited daylight you have would be brighter,” Mr. Stewart said. “It’s like an extra bulb in the chandelier for the day.”

An area that is gaining more research is how the brain responds to seasonal cues, Ms. Roecklein said.

“You associate those cues with moods,” she said.

Another colleague, she said, is researching how people respond to more enjoyable stimuli of winter, such as snuggling up to a cup of hot chocolate and reading a book.

“What we do is challenge beliefs that summer’s perfect and challenge the beliefs that winters are bad,” Ms. Roecklein said.

Ms. Roecklein said her research focuses on how the human eye is used for more than vision: It is also a portal to the brain for light.

Light sends the brain cues on how people should organize their days, through what’s known as our internal circadian clocks. That’s a brain function that influences anything from our daily wake-up routine and other behaviors, to how our digestive systems operate.

“We think if there’s not enough light for the system, it gets out of sync,” Ms. Roecklein said. “We look at winter and summer and people without depression for seasonal variability and populations with it.”

Real winters

As rough as this winter’s been on residents of the Great Lakes region and the East Coast, it hasn’t been consistently bad across North America.

Many people by now have heard about Alaska’s unusual warmth. Much of California and other parts of the West Coast have been in a prolonged drought.

One part of rural Washington state that normally gets 183 inches of snow hadn’t received any until mid-February.

For a Jan. 9 article, the Associated Press assembled a database of average, national daytime winter temperatures back to 1900.

It found cold extremes occurred once every four years until 1997.

From January, 1997, through January, 2014, national average temperatures did not go below 18 degrees — by far the longest stretch of time in that 114-year time frame.

“As the world warms, the United States is getting fewer bitter cold spells,” the article stated. “So when a deep freeze strikes, scientists say, it seems more unprecedented than it really is.”

In other words, a series of relatively mild winters since 1997 have made a lot of people forget what real winters are like.

The patterns speak to the regional anomalies of climate change and how public perceptions are shaped largely by their own backyard experiences.

Many Toledo-area residents probably don’t know that this January wasn’t even among the coldest this century for the United States.

That distinction goes to January, 2011. But that January was warmer than most between 1900 and 2000, records show.

Last week, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration issued a report that found this January was the fourth warmest on record worldwide.

This January also marked the 347th consecutive month in which global temperatures have been warmer than the average since record-keeping began in 1880. The last time they were colder than average — again, in the context of Earth as a whole — was in February, 1985.

The degree to which Americans believe climate change is affecting winter weather is much different than that of Europeans.

A 2013 study led by Stuart Bryce Capstick, a psychologist in England with a specialty in climate change, claims residents of the United Kingdom are three times as likely to associate winter anomalies with climate change as Americans.

Another 2013 study led by Lawrence C. Hamilton, a University of New Hampshire sociology professor, showed that concerns in America are briefly elevated by extreme events, then fade away. The research was presented at last August’s American Sociological Association meeting.

More on the way

Perhaps it’s best to maintain a sense of humor about the winter of 2013-14 as it starts to wind down.

That won’t be this week, though.

Gino Izzi, a National Weather Service meteorologist in Chicago, broke the bad news about this week’s freeze in his official forecast by saying two weather indicators “both paint such a bleak ... dismal ... cold ... and potentially snowy picture [the coming] week that it’s likely to leave many winter weary souls ready to curl up in the fetal position and beg for mercy from Old Man Winter!”

Mr. Izzi’s boss, Ed Fenelon, said the meteorologist was simply playing up to the beliefs many people share about this being a seemingly endless winter. Mr. Fenelon stopped short of saying this winter’s been too rough, though.

“To me,” he said, “there’s no such thing as good weather and bad weather. To skiers and snowmobilers, they love it. Snowplowing businesses are making good money from it, and people who live in warm, sunny weather, they are going to be miserable.”

Information from The Blade’s news services was used in the report.

Contact Tom Henry at: thenry@theblade.com or 419-724-6079.