Detrimental effects of lead poisoning plague Lucas Co. homes, children

5/10/2015

‘There is no safe level for lead,’ Gloria Smith, a registered nurse and lead case manager for the Toledo-Lucas County Health Department, said. Ms. Smith is working to help the families of children with elevated lead levels reduce poisoning and exposure.

THE BLADE/KATIE RAUSCH

Buy This Image

‘There is no safe level for lead,’ Gloria Smith, a registered nurse and lead case manager for the Toledo-Lucas County Health Department, said. Ms. Smith is working to help the families of children with elevated lead levels reduce poisoning and exposure.

The childhood home of Freddie Gray, who died after being injured in Baltimore police custody, setting off nationwide protests, was like so many of the homes in Toledo’s central city.

It was rundown and had peeling paint and was where tests show he was exposed to toxic levels of lead.

Aging housing stock in Baltimore and Toledo, and poverty, provide few opportunities for children in low-income families to avoid the threat of lead exposure and the cognitive and physical damage that comes with it.

Mr. Gray, who died on April 12, grew up exposed to high levels of lead paint, was diagnosed with attention deficit problems, and had a history of arrests.

Experts say children exposed to lead are at risk for anemia, behavior and learning problems, lower IQs, and hyperactivity. In pregnant women, lead can cause premature birth and slower fetal growth, as well as risk of miscarriage.

Children who are tested for lead poisoning in Lucas County go to Gloria Smith, a registered nurse and lead case manager for the Toledo-Lucas County Health Department. The first screening is a finger prick. If lead levels in the blood are elevated, another blood test is ordered within 90 days to confirm the level of toxicity.

In 2013, there were 5,628 children younger than 6 who were tested for lead poisoning in Lucas County. Of those tested, 285 children, or just more than 5 percent, had confirmed blood levels of more than 5 micrograms per deciliter of blood, the threshold that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention now designates as elevated. Eighty had a confirmed blood lead level of more than 10 micrograms, the point at which Ms. Smith opens a case.

Another 165 Toledo children had elevated levels at the preliminary screening, but their parents did not return them for a confirmation test. The CDC in 2014 lowered the poisoning threshold from 10 to 5 micrograms after continuing research showed damage at lower and lower levels. The 2013 numbers, which are the most recent available, worked under the old guidelines.

The Ohio Department of Health has identified 18 high risk ZIP codes in Lucas County. High risk ZIP codes contain at least one census tract where 12 percent or more of children tested in 2001 had blood lead levels of 10 micrograms and are further defined by demographic and socioeconomic data. One study by the Kirwan Institute at Ohio State University predicted more than 3,400 children in Toledo have lead poisoning.

Ms. Smith, who has held the health department’s lead case manager job for about 18 months, said it has opened her eyes to many facets of the problem locally.

“The challenge for me was getting over the shock and how the community thought that lead was no longer an issue,” she said.

Lucas County is above the state average of just more than 3 percent of children tested registering lead levels above 5 micrograms per deciliter.

“When I read [about Freddie Gray’s home], of course, it made me sad,” she said. “But in my job I see these Freddie Grays every single day as little children.”

A call to action

Experts stress the same message over and over again: There is no safe amount of lead. It’s a problem Ruth Ann Norton, president of the Green and Healthy Homes Initiative, calls “entirely preventable.”

Lead poisoning is like “taking the knees out from under kids before they are able to stand up for themselves,” she said, hindering their success in the classroom and the job market, often in youngsters who are already dealing with tough circumstances. She said lead levels as low as 2 micrograms have been seen to cause damage.

As a child, Mr. Gray had blood lead levels as high as 37 micrograms. He had been arrested dozens of times and had an attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, the Washington Post reported. That doesn’t excuse the circumstances of his death, Ms. Norton said, but it provides a broader picture of the environment in which he and others in Baltimore and cities across the country are living.

“It may have been a contributor to him being on the corner rather than at a job or in a classroom,” Ms. Norton said. “A child poisoned with lead is seven times more likely to drop out of school and six times more likely to enter the justice system.”

The events unfolding in Baltimore are a “call to action,” she said. The Green and Health Homes Initiative is a national organization based in Baltimore that works to integrate health-based and energy efficient improvements into homes to decrease hazards, including asbestos, mold, pests, and lead-based products. The organization currently operates in 21 cities, with Toledo possibly becoming No. 22.

“We’ve long been excited about the prospects of Toledo,” she said. “We are hopeful that we will be able to move this forward in 2015.”

Eliminating children’s exposure to lead-based products will improve third-grade reading scores, long-term graduation rates, and will reduce juvenile crime, she said. A study by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences found that every dollar invested in lead paint hazard remediation results in a financial return of between $17 and $221 in future health-care costs, special education, the criminal justice system, and lifetime earnings of those affected.

Who is at risk

The common denominator among children with elevated lead levels is poverty, Ms. Smith said. The vast majority of her cases are residents who are renting, she said. Substandard housing stock gives low-income families few choices of where to rent. Landlords don’t have many incentives to pay for upkeep and improvements.

Often parents, wanting to protect their children, want to move immediately, Ms. Smith said. It’s a natural reaction, but families often can’t afford to move anywhere safer than where they currently reside. Ms. Smith and her colleagues encourage residents to do as much as they can within their circumstances, including cleaning and other measures to reduce the risk of lead exposure, instead of displacing families.

“It’s really simple to say this house is full of lead, you have to leave,” she said. “You can’t do that. Where are they going to go?”

The easiest remedy? Frequent cleaning with supplies as cheap as soap and water, said Vaughn Jackson, who assesses children’s homes who test high for lead for the health department. Mopping floors and wiping down window sills can reduce dust and paint chips that might contain lead.

He said it is difficult to estimate how many dwellings are poisoning residents. In any home built before 1978, the year the federal government outlawed lead-paint use for residential properties, there’s a “good chance” it’s laden with lead. U.S. Census data estimates more than 158,000 housing units in Lucas County in 2013 were built in 1979 or earlier.

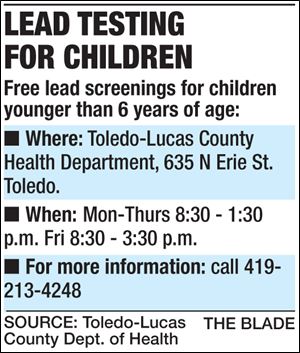

Children get tested locally through a variety of avenues. All Head Start students in Toledo are required to be tested, as well as all children on Medicaid, although not all of those tests are followed through on. Parents also can take children younger than 6 to the health department for free lead testing.

‘Lead baby’

Ms. Smith sees the detrimental effects firsthand, describing one toddler tested as “our classic lead baby.” The toddler showed several signs of poisoning, including poor appetite and hyperactivity. Tests showed he had more than 45 micrograms of lead per deciliter in his blood.

Anything above 45 micrograms is coded as red on the CDC chart of exposure levels and requires chelation therapy, a medication that binds itself to lead and is then excreted through waste.

Ms. Smith looks at the child’s living situation on the whole: the conditions of the home, day cares, and other dwellings where he or she spends time; pets that could bring in lead-ridden soil into the home and toys or other objects that could contain lead.

In the case of that toddler, investigators discovered he spent several hours a day with relatives in the Old West End, where the home had peeling paint and other hazards.

When a case is opened, it stays open until two follow-up tests show the child’s levels have dropped lower than 10 micrograms per deciliter, she said.

The universality of lead in the community hit Ms. Smith shortly after taking the job, when her predecessor returned from a site visit with descriptions of deplorable conditions. As the assessors detailed the home riddled with lead risks, Ms. Smith looked at the address. And then looked again.

“We used to live in that house,” she told them. She remembers the house, then well-kept in a nice neighborhood but with chipping paint, and thinks of her five younger brothers, who she said have signs of attention deficit.

“And I ended up in the lead program,” she said. “It comes full circle.”

Finding solutions

The CDC last week issued a report detailing educational interventions for children who have already been exposed, the first of its kind. In Lucas County, those working to eradicate lead poisoning say the system waits for children to be poisoned, often after irreversible cognitive and physical damage is done.

In February, the Toledo Lead Poisoning Prevention Coalition began meeting, joining together with officials from the health, legal, and civil rights realms to analyze the issue comprehensively. Among those involved are representatives from Advocates for Basic Legal Equality, Toledo Fair Housing, the health department, Toledo NAACP, and the University of Toledo Medical Center, the former Medical College of Ohio.

Robert Cole, managing attorney at ABLE and a member of the coalition, said more needs to be done to prevent poisoning before it happens.

“If you have a 5 [microgram per deciliter] exposure, you’ve likely lost one IQ point,” he said.

The coalition is working to get a city ordinance in place that would require properties built before 1978 to be tested for lead before they are rented out, as well as additional educational and preventive tools for residents.

Toledo Public Schools currently does not track how many of its students are lead poisoned, TPS spokesman Patty Mazur said, although Head Start students in the district are all required to be tested.

Mr. Cole said the coalition has invited TPS representatives to future meetings in an effort to broaden the collaborative effort.

“The whole system waits to respond until the child is lead poisoned,” Mr. Cole said. “Essentially we’re using children as lead detectors.”

Contact Lauren Lindstrom at llindstrom@theblade.com, 419-724-6154, or on Twitter @lelindstrom.