DEVELOPMENTAL HELP

Program trains parents to give children therapy

PLAY helps with autism spectrum disorder

8/16/2015

“It's working towards a purpose,” Erin Luetzow said about the PLAY therapy she uses to help her autistic sons, Kruze, 3, center, and Gage, 4, right. The program includes using their self-directed play to help work on their impairments.

The Blade/Katie Rausch

Buy This Image

“It's working towards a purpose,” Erin Luetzow said about the PLAY therapy she uses to help her autistic sons, Kruze, 3, center, and Gage, 4, right. The program includes using their self-directed play to help work on their impairments.

Having one child with autism spectrum disorder can be challenging, but Rossford parents Erin and Ryan Luetzow have two young boys with ASD who also display very different behaviors.

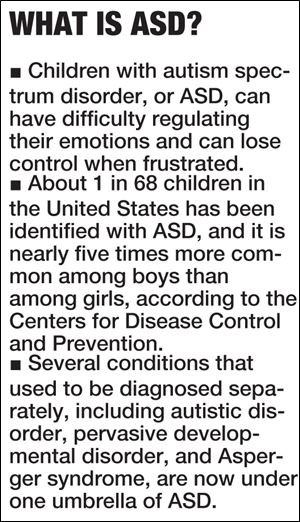

Children with ASD can have difficulty regulating their emotions, and they can lose control when frustrated. They can be socially isolated and have language delays.

The Luetzow family recently turned to an innovative therapy called the PLAY Project (Play and Language for Autistic Youngsters) to help their sons, Gage and Kruze. Developed by a local doctor, the program focuses on training parents and giving them skills to help their child’s development through playing with them during everyday activities at home.

Gage, 4, never had what Mrs. Luetzow called traditional autism symptoms.

“We actually didn’t find out until after I had Kruze,” she said. The boys are 22 months apart.

“Gage had a speech delay, but the furthest thing from my mind was autism, because he gave us eye contact and he loved playing with other kids,” she said.

Kruze, 3, however, is content to play alone for hours, not seeking interaction with anyone. “I just thought he was a good second kid. He played on his own wonderfully. Well, that’s because of the autism. He is not concerned with playing with other people or kids and stuff,” she said.

Just before Kruze’s second birthday, Mrs. Luetzow told her family pediatrician about some behaviors that are considered red flags, such as speech difficulties and that he was seemingly in his own world much of the time. The doctor referred her to the Mercy Autism Services in Maumee, where they connected with Dr. Richard Solomon, who developed the PLAY therapy.

Diagnosing ASD

Dr. Solomon said there has been a dramatic increase in the number of children being diagnosed with ASD in the past 25 years. He attributes the increase to parents and health professionals being more aware of the signs and symptoms, especially pediatricians. He said doctors are diagnosing children at an earlier age and getting them into intervention therapy.

About 1 in 68 children in the United States has been identified with ASD, and it is nearly five times more common among boys than among girls, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Several conditions that used to be diagnosed separately, including autistic disorder, pervasive developmental disorder, and Asperger syndrome, are now under one umbrella of ASD.

“Some people have said the classic severe autism has not increased. We are diagnosing it milder, and that is what has increased,” said Dr. Solomon, who in addition to being the medical director for Mercy’s autism program also runs the Ann Arbor Center for Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics.

He calls PLAY a radical departure from typical programs because it uses the train-the-trainer model. A therapist visits the home once or twice a month to observe the parents and to give them ideas to teach the child the skills he or she needs. Then the parents take over as the therapist.

“The cost is about one-tenth of traditional services because the parents are delivering it,” he said.

Learning to PLAY

For the Luetzows, Mercy PLAY consultant Shelly Bieszki has visited once a month since December for about three to four hours each visit. She usually spends time playing with the children, to give Mrs. Luetzow some examples of how to handle different situations, and then she records Mrs. Luetzow interacting with the children. The consultant will often review the tape with Mrs. Luetzow to give her feedback, which is also available for her husband to review, Mrs. Luetzow said.

The consultant is teaching Mrs. Luetzow how to work with each child differently. Gage, who was also diagnosed by Dr. Solomon, is very high functioning, his mother said. Unlike some children with ASD, he is outgoing, talkative, and friendly, so it is not always obvious to people that he has ASD. His mother fears that when she is at family functions or at places like the grocery store that others are judging her if he begins to act out.

Dr. Richard Solomon, medical director of Mercy Autism Services in Maumee, developed PLAY therapy for autism.

It is common for children with autism to have difficulty regulating emotions, which can lead to aggressive behavior or the tendency to lose control, according to Autism Speaks, a leading autism advocacy organization.

Mrs. Luetzow, who is a former hair stylist, stays home with the children and spends about 20 to 30 hours a week using the principles she is learning through the program.

“Let’s say a child with autism likes to jump and the parent sees that — they can read the cues and engage the child in a way that’s fun by playing a jumping game with the child. They can get right up on the couch and jump with them,” Dr. Solomon said.

Mrs. Luetzow and her husband don’t try to do all the therapy in “one chunk,” she said. Instead, they try to choose natural settings like bath time or bedtime to have fun with the children.

The PLAY Project requires sacrifice on the part of the parents because it is a huge commitment of time and energy, but it is also empowering for parents who often feel helpless in the face of the disorder, Dr. Solomon said.

Some parents find the method surprising, because they are following the child and doing what the child loves. “We are joining the child’s world and having fun with them and then they let you in,” he said.

Mrs. Luetzow said she has seen remarkable changes in her boys. She remembers vividly the first time Kruze, who is very inward-focused, looked her in the eyes and connected with her.

Erin Luetzow plays with her autistic sons, Kruze, 3, left, and Gage, 4. She uses their self-directed play to help work on their impairments. Gage, for example, loves to play with trains. "I know that the more emotion I put into those trains," Erin said, "the more that it's helping him interact with people."

“He would always come up to me, but now he looks at me. It’s the greatest feeling ever. It’s awesome,” she said.

Her goal with the program is to get both boys ready to enter school in a “normal kindergarten setting,” she said.

Program availability

The Luetzow family paid $4,000 for the PLAY training through Mercy Autism Services, which is a private agency. Thirty-one Ohio counties are certified in the program and offer it through the county developmental disability agencies.

Wood County is still working on its certification, said Kerry Francis, spokesman for the Ohio Department of Developmental Disabilities. Seventeen other counties in the state have access to the program by using resources in a neighboring county that has completed the certification, she said.

The PLAY program is free to some families in Lucas, Fulton, and Sandusky counties if the child is found to have a certain level of developmental disability, Ms. Francis said.

Dr. Solomon called Ohio an early adopter state, but he expects many other states will follow now that he has published the findings of a three-year study of the program in the Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics.

The study, one of the largest of its kind, followed 128 families of children aged 3 to 6 with ASD in five cities, he said.

Erin Luetzow uses her sons’ self-directed play to help work on their impairments. Gage, for example, loves to play with trains. ‘I know that the more emotion I put into those trains,’ Erin said, ‘the more that it’s helping him interact with people.’

After one year, children assigned to the PLAY Project group showed greater improvement in social skills, compliance, emotional development, and autism symptoms than children in the study who were assigned to other community service programs, Dr. Solomon said.

Amazing changes

Heidi VanHeuklon of Peoria, Ill., said her son Aidan was one of the participants in Dr. Solomon’s PLAY Project research study when he was 3.

“He would want things to go his way all the time and he had very little tolerance for changes in schedules. He would get overstimulated easily going out places and then he would act out,” Mrs. VanHeuklon said.

After a year in the program, her family saw a positive change in Aidan’s behavior.

“Honestly, all of the initial behaviors that we were targeting had greatly improved. He threw toys at the researcher at the preassessment. By the end at the post, he was interacting with the researcher. It was like night and day difference,” she said.

Aidan, now 7, is starting second grade this fall and the people at school don’t know he has autism, his mother said.

Contact Marlene Harris-Taylor at mtaylor@theblade.com or 419-724-6091.