SCAVENGING FOR HOPE

Detour in Guatemala gave priest new direction

Ex-Toledoan started group after accident

7/4/2011

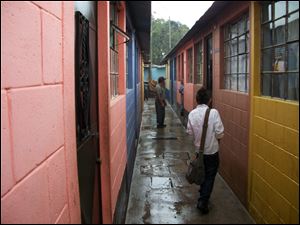

International Samaritan built these concrete-block houses in a neighborhood near the Francisco Coll school. The houses replace shanties made of plastic, cardboard, and tin where dump workers previously lived. The concrete-block houses have running water, a bathroom, and electricity and provide a sense of pride and safety.

The Blade/David Yonke

Buy This Image

The Rev. Don Vettese joins students and staff at Francisco Coll school, built by International Samaritan, which he began as president of St. John's Jesuit High School.

Second of two parts

GUATEMALA CITY -- International Samaritan, a nonprofit organization founded in Toledo to help victims of extreme poverty around the world, started by accident -- a traffic accident.

The Rev. Don Vettese, a Jesuit priest, was president of St. John's Jesuit High School when he led a team of students on a service trip to an orphanage in Guatemala City in the summer of 1994.

An accident forced the van the team was riding in to take a detour, and the school group wound up stopped in traffic beside the garbage dump in the notorious Zone 3.

The neighborhood is the poorest, most dangerous, and foulest-smelling section of this capital city, a place where few tourists ever venture.

The scene seemed like a nightmare to the visitors as droves of people scavenged through trash in search of plastic, glass, metal, and other materials they could sell to recyclers.

"There were hundreds and hundreds of people recycling, and there were cows and pigs feeding there, and infants were just stuck in the garbage by their parent so they couldn't move around," Father Vettese recalled. "It was in the 90s -- humid, hot, and sweaty. There were smoldering fires and smoke everywhere."

Children banged on the school's van, begging for food, money, and help.

"The delay was only about 20 minutes but it seemed like forever," Father Vettese said. "You're reduced to absolute silence, unable to speak. It was unutterable. Nobody in the van talked. We just sat there taking it all in. It was a scene from hell."

Afterward, the St. John's students and the priest engaged in a long conversation.

"They wanted to know what we could do," Father Vettese said. "I had no idea, so I said, 'Let's talk about this.' "

Everyone's first concern was to find a way to get the children out of the dump.

Father Vettese set up a meeting with Oscar Burger, at the time the mayor of the city of 1.5 million. Mr. Burger later served two terms as Guatemala's president.

"I described what we saw. He knew, of course," Father Vettese said.

Mayor Burger asked the priest if they could work together to help improve the plight of dump workers and others living in Zone 3.

PHOTO GALLERIES:

Life in Guatemala City Ghettos

St. John's Visit to Guatemala Schools

RELATED ARTICLES:

Guatemalan laborers get help from Toledo

St. John's students serve as role models

Strides made in improving worker' health, safety

Education offers dump worker a way out

Memories of dump life in Guatemala are hard to shake, 7/4/11

Blessing gone global

A nursery schooler looks at the braces on Mark Brahler's teeth during the trip by St. John's students to work at the school funded by International Samaritan.

With the blessing of his Jesuit order, Father Vettese incorporated the nonprofit organization a year later in Toledo, originally calling it Central American Ministries but renaming it International Samaritan in 2009 to reflect the growing global outreach.

In 16 years, the ministry has started programs to alleviate severe poverty in seven countries -- Guatemala, Egypt, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, Panama, and Haiti -- and is conducting feasibility studies for similar efforts in Ethiopia, Sierra Leone, and the Philippines.

Each year, it serves about 13,000 people stuck in extreme poverty, operating on an annual budget of about $2 million. Nearly 95 percent of the income goes directly to ministry, with 5.2 percent used for administrative costs.

Father Vettese would like to expand the programs to every garbage dump in every developing country in the world.

The same scenario he witnessed in Guatemala exists everywhere today, he said, except for the United States, western Europe, and Australia.

"The need is almost unlimited. We're talking about millions of people. I'll go as far as I can -- as far as my energies and resources and the people who share with us will take us," he said.

The plan in each community is to start with a nursery to get the children out of the garbage dump.

The next step is to provide education, because that is viewed as the key to breaking the cycle of poverty.

International Samaritan first builds a grade school, then a middle school.

In Guatemala, where efforts have been ongoing for 16 years, there is a program that matches middle school graduates with local high schools, with the goal of getting students into college.

All along the way, International Samaritan builds modest homes for dump workers who typically must live in shanties made of plastic, cardboard, and tin. The concrete-block houses have running water, a bathroom, and electricity, and give the families a sense of pride and safety.

Help from the U.S.

Teams of high school and college students from the Toledo area -- including St. Ursula Academy and the University of Toledo -- as well as throughout the country have traveled to different International Samaritan sites to help in a variety of ways. Some trips focus on construction and renovation work and others teach English to dump workers' children. Many U.S. visitors have said the trip was life-changing, Father Vettese said.

"The services we're doing may be greater to the travelers than to the people down there," he said, adding that one of the most rewarding things about his work is "watching the hearts of young people open up as the Spirit draws them into compassion."

For the first 12 years after the founding of International Samaritan, Father Vettese balanced his duties as St. John's president while leading the outreach to dump dwellers. In 2007, he left the school to begin working full time as president of International Samaritan and moved the headquarters to a house in downtown Ann Arbor. He lives next door with his dog, Pagan.

Father Vettese works diligently at fund-raising, needing to bring in an average of $6,500 every day to meet the current budget.

"I am not afraid to ask for money, not for something as important as this," he said. "What's the worst that can happen? They can say no. But that doesn't mean no forever. I can always come back."

The biggest single check International Samaritan has ever received was for $1 million, he said. That same donor, whom he did not identify, has given more than $6 million over the years.

At the other extreme, people have donated the contents of piggy banks and some students have organized fund-raisers, such as a long-distance bicycle ride with sponsorships.

Frequent surprises

International Samaritan built these concrete-block houses in a neighborhood near the Francisco Coll school. The houses replace shanties made of plastic, cardboard, and tin where dump workers previously lived. The concrete-block houses have running water, a bathroom, and electricity and provide a sense of pride and safety.

Father Vettese, who was ordained a priest in 1977, sets lofty spiritual goals and has ambitious visions, yet he is down to earth when it comes to dealing with the road blocks that can pop up in developing nations.

On March 3, for example, International Samaritan held a ceremony, attended with great fanfare by local civic, church, and government leaders, to dedicate a new middle school it built in Zone 3, just around the corner from its Francisco Coll grade school.

But before the school could hold its first class, Guatemala City officials took over an International Samaritan nursery to use for a city school.

The move surprised Father Vettese and his staff.

"I wouldn't have minded if they had asked, or if we had discussed it," he said. "We could have worked something out."

International Samaritan had no choice but to move the nursery into its new building, putting the middle school on indefinite hold.

In a visit to Guatemala last month, Father Vettese and Oscar Dussan, International Samaritan's executive director, met with U.S. Ambassador Stephen McFarland, Guatemala City Mayor Alvaro Arzu, and Mayor Arzu's wife, Patricia de Arzu, who is running for president.

The diplomatic discussions ultimately resulted in city officials agreeing to move the school out of the nursery by Jan. 1.

It's the kind of scenario Father Vettese has come to accept after 16 years and "hundreds" of trips to Central America.

"First of all, the governments aren't the most stable. And they're not as mature as our government structure," Father Vettese said. "It requires a persistence on our part and a willingness to think a new thought and develop a way for them to work in the service to their people.

"In a way, it's working," he said. "But it's also challenging."

Leading by example

International Samaritan is a Christian ministry that lets its service to others be a testimony, rather than outright proselytizing.

"We're not trying to convert people to Catholicism, but the fact of the matter is they know we are Catholic. They know we are Christians. We're evangelizing through example," he said.

Serving the poor is something that represents the values of Christianity, Catholicism, and the Jesuit order, Father Vettese said.

He cited Jesus' words in the Bible's book of Matthew: "Whatever you did to the least of these brothers of mine, you did for me."

Margarita Lara, a translator for International Samaritan in Guatemala, said Father Vettese always finds a way to get things done.

"He wants to do so much, and he has so much energy!" Ms. Lara said. "And he is involved. He is everywhere. Father Vettese believes in this mission so much that it's contagious. He gets you to say, 'I'll give it a shot.'

"And he's a patient man," she said. "He'll wait as long as it takes to get his way -- and he usually does get his way."

Contact David Yonke at: dyonke@theblade.com or 419-724-6154.