Vanished shipwreck’s secret revealed

Sunken vessel swallowed up by Lake Erie muck

3/19/2012

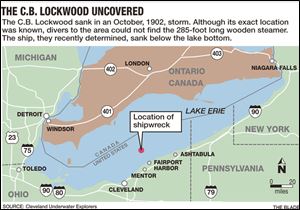

The C.B. Lockwood sank in October, 1902, and its exact location just east of Cleveland has been known ever since. But shipwreck hunters were baffled because the wreck wasn’t there. Researchers say that the ship is under the lake bottom.

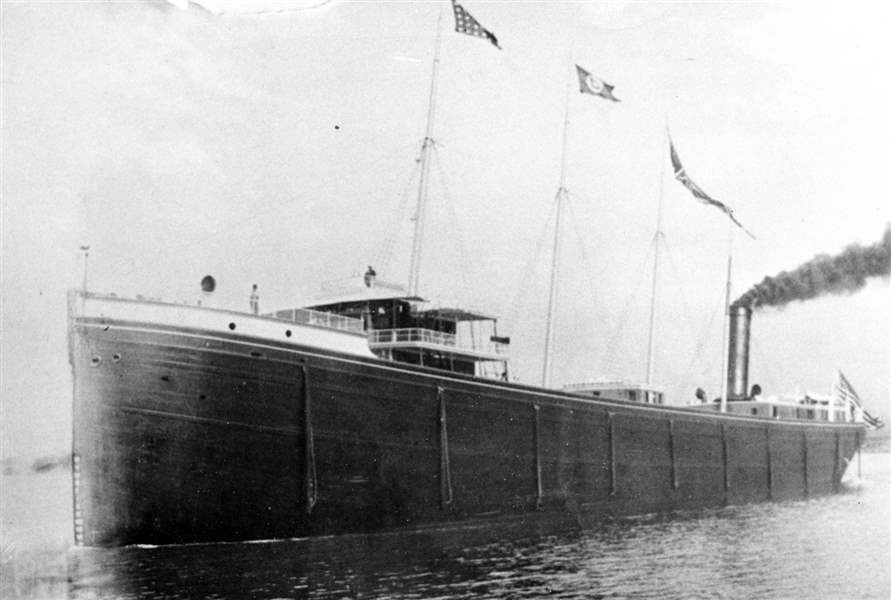

Photo Courtesy of the Charles Frohman Collection at the Hayes Presidential Center

The C.B. Lockwood sank in October, 1902, and its exact location just east of Cleveland has been known ever since. But shipwreck hunters were baffled because the wreck wasn’t there. Researchers say that the ship is under the lake bottom.

CLEVELAND — Twice during its 122-year history, the C.B. Lockwood has been swallowed up by Lake Erie.

On course from Duluth, Minn., to Buffalo and battling the fury of an October storm, the 285-foot wooden steamer first sank in 1902, crashing more than 70 feet below the waves just east of Cleveland.

The location of the Lockwood was not a mystery. With one look at historical data, its exact location — 13½ miles north by northwest off Fairport Harbor — easily can be found. But despite being armed with a figurative “X marks the spot,” shipwreck hunters have for decades been stumped by the empty expanse of Lake Erie muck where the Lockwood should be.

Until now.

More than a century after its sinking and with the use of sophisticated equipment, researchers recently determined that the Lockwood never moved, it simply sank again.

“It sank twice, once to the bottom and once below the bottom,” said shipwreck hunter David VanZandt, the director and chief archaeologist for the Cleveland Underwater Explorers, or CLUE, who discovered the twice-sunken ship.

“The entire ship was under the lake bottom,” he said. “The lake swallowed up a 300-foot wreck.”

But how?

What is known about the Lockwood has been learned through newspaper articles and maritime records. Launched from Cleveland on June 25, 1890, the Lockwood was at the time the largest wooden steamer on the lakes and the first lake propeller ship to measure 45 feet in width.

According to records provided by CLUE, the Lockwood broke a Sault Ste. Marie-to-Duluth speed record one year after its launch. But it sailed for only a dozen years when it came across bad weather while hauling a cargo of flaxseed.

The ship sank on Oct. 13, 1902, forcing its crew into two lifeboats. One boat made it to shore, the other did not. Ten crew members died.

Within days of its sinking, the Lockwood was found and charted. Within weeks, the wreck was marked with buoys. But yet, decades later, scuba divers can find only a few empty lifeboat cranes and some strange markings in the muck when they go to the site.

“The difficulty about it [is] we had excellent location information,” said Clue chief researcher Jim Paskert, who began looking for the Lockwood in the mid-80s. “We redid the map and checked all the information, and ‘Boy, this is where it should be, and we’re here, and there’s nothing here.’?”

That is, until the group was given access to a subbottom profiler — a device that penetrates the seabed to highlight seismic structural differences and layers that are hidden from view. Using the technology, the group discovered that in fact a structure was there — about 285 feet long and 45 feet wide.

Think of it as a jar of sand with a marble on top, Mr. Paskert explained. When the jar is shaken, the sand shifts, forming air pockets, and the marble sinks.

Research of Ohio earthquakes showed that the Lake Erie basin has experienced several — most of them occurring under the lake in the northeast corner of the state.

The team coupled that information with the fact that a dive to the Lockwood site with a 10-foot pole showed that the lake bottom, although flat, was not solid. Instead, the glaciers that formed the Great Lakes must have left a valley in the floor that was covered up with the hundreds of years of sediment collecting in Lake Erie.

The Lockwood, they hypothesized, sank right into one of those valleys.

The discovery of the Lockwood’s fate has opened a new possibility to those studying Great Lakes history, said Chris Gillcrist, executive director of the Great Lakes Historical Society.

The nonprofit society, which is slated to open its maritime museum in Toledo in May, 2013, supports the efforts of groups such as CLUE through help in funding searches, Mr. Gillcrist said. And now with the knowledge that some shipwrecks can be swallowed up by the lake bottom, researchers have another possibility to consider when seeking out their next target.

“Nobody has done this type of scientific study of a wreck on the Great Lakes, ever,” Mr. Gillcrist said of the scientific theory of liquefaction. “We don’t have any evidence of this happening on the western basin [near Toledo].”

The Lockwood is just one of the thousands of shipwrecks that litter the floors of the five Great Lakes. In Lake Erie alone, hundreds have been found and hundreds more are waiting to be discovered.

Paul LaMarre III, manager of maritime affairs for the Toledo-Lucas County Port Authority, noted the important role of the Great Lakes in the creation of Toledo, which began as a port. He said continued research and discovery in the lakes only further proves their importance in national and maritime history.

“The Great Lakes provide such a sensational platform for shipwreck [scuba] diving and research,” he said. “There’s nowhere else in the world that ships of this size sail or have sailed on freshwater. Because of that, the ships are better preserved than anywhere else in the world, depending on the depth.”

CLUE, a nonprofit group of divers, historians, and archaeologists, has shared its findings on the Lockwood in presentations across the Great Lakes.

Recently, the disappearance of the Lockwood was the focus of at the Association for Great Lakes Maritime History’s 27th annual conference in Toledo. The group’s Web site isclueshipwrecks.org.

And in each of their presentations, members of the shipwreck hunting team offer something they are not usually quick to reveal — the exact coordinates of the ship’s final resting place, N 41 56.480 W 81 23.510. You can go to the ship, they offer, but there isn’t much to see.

“This is the first time I’ll tell you exactly where it is,” Mr. VanZandt said.

Contact Erica Blake at: eblake@theblade.com or 419-213-2134.