Building a future on a shoestring budget in Pomeroy

Appalachian residents see hope in Trump’s push for coal, but they aren’t waiting for possible boom

9/15/2018

A Civil War memorial overlooks the Meigs County Courthouse. The original courthouse construction was completed in 1845, with additions erected in the late 1870s.

THE BLADE/KATIE RAUSCH

Buy This Image

Third in a five-part series

POMEROY, Ohio — Maj. Scott Trussell, second-in-command at the Meigs County sheriff office, leaned back in his office chair.

Above filing cabinets and county maps, the wall had fragmented, pieces of old paint crumbling. Leaks in the ceiling had developed into small brown craters.

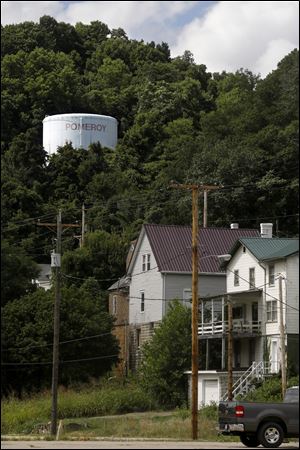

A tower bearing the name of Pomeroy overlooks a church and several homes near the city's downtown.

Above the sheriff’s office and county jail, chimneys, close to collapsing, were partially taken down this summer. The front steps have shifted several inches away from the building’s foundation, likely because the building itself is falling backwards, Major Trussell said.

Second story jail cells have been converted into an evidence room. Black mold has developed in the basement.

“As a sheriff’s office and jail, it’s outlived its use,” he said. “The building is deteriorating. ... The foundation is collapsing underneath all of it.”

The jail holds five inmates, a fraction of the county’s jail population, and it’s often over capacity. Officers may travel as far as Lucas County, 239 miles away in the opposite corner of the state, to house the overflow. The county spent $287,704 in 2017 on jail beds across Ohio.

PHOTO GALLERY: Scenes from Pomeroy

Blade Series: Views from small-town Ohio

The county commissioners and sheriff’s office have developed a plan to create a new facility — with 71 jail beds so that Meigs can make a profit by leasing to other counties in the state — and a drug treatment facility.

For Meigs, more and more residents have fallen to opioid and meth addiction ever since the coal jobs left years ago, several residents told The Blade. In 2016, 103 overdoses were reported to the emergency room, 12 of which resulted in deaths. County Prosecutor James Stanley said that, on average, 70 percent of the indictments each month are drug-related.

Still, residents of Meigs County don’t want to pay for the new jail and drug-treatment facility. Voters twice struck down a proposed levy to build a new jail: once in November, 2017, and again in May, 2018. The 2.95-millage was just too much for some county residents, Major Trussell said.

“It’s really about saving your money or helping your fellow people,” he said. “Nobody looks to the future, and that’s what we were trying to do.”

For a county still grieving the loss of coal, a new jail is the least of its worries. Residents are still waiting for new industry to pull into the ports where coal steamboats once docked, many counting on President Trump to fulfill his campaign promise to the region.

Paint chips off the densely-packed houses, and several storefronts remain vacant along the main drags in the county’s townships. Along the county’s oftentimes circuitous streets, residents sip coffee in rocking chairs on their old porches, waving to neighbors and gossiping about small-town scandals. Locals rarely leave town, except for the occasional trip to Walmart across the river in West Virginia.

Meigs was once thriving. But now, fed up with the area’s dormancy and the rotating door of storefronts that cycle through Main Street, residents and merchants are taking a seat at the table to strategize: How can they carry on those memories of better days while creating a new legacy for the county — making do with what they have and spending as little money as possible?

Coal and salt

Meigs County, located in the southeastern corner of the state, often competes with neighboring Appalachian counties for the poorest in the state. In its 17 villages and townships, pockets of poverty sit amidst open greenery and farmland.

The median household income is $39,640 and the per capita income is $21,317, according to U.S. Census figures. Twenty-one percent of the population lives in poverty. In Pomeroy the figure is nearly 39 percent.

Meigs County Commissioner Tim Ihle, a beef cattle farmer by trade, says he has little time for national politics.

In Ohio, by contrast, the median household income is $50,674; the per capita income is $27,800 and 14.6 percent of the population lives in poverty.

And unlike in Toledo and other urban centers in Ohio where there is a high concentration of poor black neighborhoods, in Meigs County and Pomeroy the poor are predominantly white — many of them Trump voters.

The county’s population is 97 percent white.

Levies raise less

Pomeroy’s Meigs Local School District in 2017 taxed real property at a rate of 20 mills, bringing in about $2.4 million. In Lucas County, by contrast, residents in Ottawa Hills paid 80.65 mills in real property tax to their district last year. Those payments generated nearly $12 million for Ottawa Hills schools.

The last property tax levy for operations in Meigs Local was approved back in 1976.

The Meigs County Sheriff’s Office and jail has room for five inmates at a time, causing the county to pay to house inmates elsewhere across the state.

The two districts’ state-issued report cards for the 2016-17 school year illustrated additional disparities. While Ottawa Hills scored A grades across categories like K-3 literacy, graduation rate, and students’ preparedness for success, Meigs schools scored — outside of a B in the category that tracks how students are progressing against past performance — all D’s and F’s.

Less than 40 percent of third graders in Meigs schools earned proficient scores on state reading tests compared to nearly 95 percent in Ottawa Hills. In Ottawa Hills, 24 percent of ACT test takers in 2015 and 2016 earned scores deemed to be remedial for the college entrance exam. In Meigs schools, 92 percent of the ACT takers earned remedial scores.

Only 13.5 percent of people in Meigs County have obtained a bachelor’s degree or higher, while 16 percent of people lack even a high school diploma, according to state data.

The county’s not-seasonally-adjusted unemployment rate was 7 percent in July, 2018. Statewide the figure was 4.9 percent.

Jordan Pickens, a lifelong resident of the county, is a school teacher at Southern, from which he graduated in 2009.

He and his wife, Calee Pickens, met in high school, while he was the drum captain in the marching band at Southern and she at Meigs, another local high school. They now have an 18-month-old son, Andrew, whose toys line the front porch of their home in Pomeroy, the county seat.

“Taxpayers are tired of being burdened with the cost of improvement in Meigs County,” said Mr. Pickens, who ultimately decided to vote in favor of the jail. “We feel burdened that the people who own property are the ones that would have to pay. They have to find another way to do this.”

Mr. and Mrs. Pickens both have stable jobs at the school, but they still live paycheck to paycheck, paying the hospital bills for their son’s delivery a year and a half later.

Mrs. Pickens offered Andrew a few Cheerios, of which he was not interested. The three were getting ready to go to Food Truck Thursday in Middleport, a neighboring town in Meigs, but it was getting late. Andrew needed to get cleaned up first.

Outside the classroom, Mr. Pickens is also a local historian; he co-authored a book on the county’s history.

Meigs County was established in 1819, the same year as the first coal mine in Pomeroy.

Pomeroy is the county’s second-largest village. With a population of roughly 2,500, Middleport — so named for the community’s halfway point between Cincinnati and Pittsburgh along the Ohio River — has about 600 more residents than the neighboring county seat.

Not far away is the unincorporated community of Chester, home to the original Meigs County Courthouse. Built in 1823, it is the oldest standing courthouse in Ohio, but was abandoned when the county seat moved to Pomeroy in 1841.

It was in Pomeroy that Valentine B. Horton invented the coal barge and first coal-fueled towboat — introducing large-scale transportation of coal by river. For Meigs County residents, many of whom leave for college but are reeled back by family history, that ingenuity is a point of pride.

“This county was founded on the back of coal and salt: predominant exports, what employed pretty much everybody,” Mr. Pickens said.

In The Pioneer History of Meigs County , Stillman Carter Larkin described how the period from 1830 to 1840 marked the beginning of commercial prosperity in the area, when “English and Welch men of experience and judgment took charge of the mines, and miners from England, Wales, and Germany went into the coal tunnels” and “with pick and hand-car brought to light the wealth of the hills.”

In the height of production in the 19th century, local mines employed thousands of people. Slowly opportunities dried up.

A resurgence of coal jobs offered a regrowth to the county in the 1970s. But again, the mines shuttered. Some were able to continue working in mines in West Virginia, just a few hundred yards away on the other side of the Ohio River.

Today a plurality of Meigs County work force members are employed in the private service sector, according to the most recent state data. The next largest segment of workers are employed by local governments: Eastern Local Schools, county government, Meigs Local Schools, and Southern Local Schools.

Notable private sector employers include Arbors at Pomeroy — a hospice facility — and Overbrook Rehab Center, a physical rehabilitation center in Middleport.

There are no hospitals in Meigs County, according to Ohio’s Developmental Service Agency.

And in a county with a median age of 42.8 and nearly half the population 45 or older, there are only two nursing homes with 199 total beds.

Trump in miner’s hat

Most people here receive cable news out of Charleston — where, in 2016, President Trump donned a miner’s hat and mimed a coal-worker at a campaign rally, signaling his allegiance to the industry Meigs residents had mourned for years.

The county has voted Republican in all but four presidential elections since the turn of the 20th century. In 2016, Mr. Trump won 73 percent of the vote.

“A lot of our heritage with coal, we associate more with West Virginia than Ohio,” Mr. Pickens said. “I think when [Trump] gave the speech that said we’re going to [have] a lot of miners put back to work in West Virginia, I kind of thought we wanted to be a part of that bandwagon.”

Mr. Pickens said he doesn’t think the county will ever see another mine open there. The county needs new industry, he added.

“You see all the time the President talking about all these jobs coming back from certain places like Mexico and China,” he said. “You hear all these great things, but it’s just life as usual in Meigs County.”

Thriving, growing

Homes nestled into the Appalachian foothills are pictured Friday, July 20, 2018, in Pomeroy, Ohio.

But amid prolonged grief over coal jobs, local shop owners have tried to maintain a flow of visitors, and revenue, into the county once known for industrial ingenuity.

On Main Street in Pomeroy, a facade along the Ohio River, time appears to have stopped while coal created hustle and bustle in the town. Steamboats still chug along the waterway, and bright colored old time storefronts are something out of the early 20th century, with an antique shop and fabric store. Few are empty — the area is at the best it’s been in a while, said Perry Varnadoe, longtime county economic development director.

About 15 years ago, a Walmart opened across the river, forcing many Main Street shops out of business. They couldn’t compete with the superstore’s prices, said Mr. Varnadoe. But after five years and a slew of speakers guiding local proprietors, the community bounced back, he said.

“Right now, business is pretty good,” he said. “It’s probably a healthier downtown than we’ve had in many years. … [Businesses are] thriving, growing, doing well.”

Tuckerman’s, a new face in Pomeroy, just moved to town a month ago. Inside, you can still buy the same bottle of pop and 5-cent Tootsie Rolls you got as a kid.

The shop had been located along the main drag in the neighboring town of Middleport — reopened at its original building after decades of vacancy. For years, Tuckerman’s Grocery Store operated at 297 Lincoln St., selling penny candy and sodas. But the streets had recently been blocked off and dug up for sewage construction. A lack of business forced the Tuckerman’s second iteration to move to Pomeroy, said store owner Amy Blake.

For Connie Patterson, jobs in Pomeroy are important. She leaned back in the rocking chair on her front porch, beside a mug of coffee and a pack of Marlboros. Dressed in her tie-dye purple uniform, she said she soon had to head off to McClure’s Restaurant, the local diner where she’s worked for 47 years.

She couldn’t really say what was so great about President Trump, but she just really didn’t like Hillary Clinton.

“I don’t know, I just didn’t care for her,” she said. “I think he’s doing a good job.”

There are more jobs now, she said — something necessary in Meigs County. But Ms. Patterson doesn’t talk politics much.

Down the road, Bulah Casto similarly sat on a bench on her front porch, like many other residents in Meigs who simply enjoy waving to the passers-by who they’ve known for years.

Ms. Casto has lived in Meigs County for 50 years. But unlike her neighbor — and most of the county — she was not a fan of the commander-in-chief. In fact, she’s a Democrat.

“I think he’s a liar. ... It’s all about him, not about the country,” she said. “You don’t have many Democrats [in Meigs County].”

A lot of people talk about how the economy is doing better, but that really all started with President Barack Obama, Ms. Casto said. She has one friend who decided to support Trump just for his party affiliation.

“He doesn’t think about the little people. It’s about him and his friends,” she said.

And the coal mines are not coming back, she added.

And we’ll go on

But as local residents hope to revitalize the area to bring revenue back to Pomeroy, dilapidated county buildings still loom over the facade of Main Street just a few yards uphill. After being voted down twice, a levy for the new jail is off the table for the time being.

County commissioner Randy Smith emphasized that residents did not vote down the measure out of unconcern for their neighbors.

For a long time, the area had “a spirit of apathy,” that it was just as good as it’s going to get, Mr. Smith said. But that’s changing.

In February, the Ohio River flooded Pomeroy’s main drag, filling the storefronts along Main Street with muddy water. A month and a half passed before many could reopen. But residents came to the front line, helping to pick up merchandise to protect those proprietors when the town could not rely on the Federal Emergency Management Agency, said Mr. Smith.

“The first thing that happens when the river comes up, every able bodied person in this community comes down to Main Street to get their stuff off before the river comes in the store,” he said.

The county receives aid when it’s convenient for political gain, Mr. Smith said. He thinks Ohio Gov. John Kasich has forgotten about the needs of counties like Meigs. When he sees Mr. Kasich on the news, for TV appearances about Mr. Trump or Congress, it makes “the hair on the back of [his] neck stand up.”

“I want [Mr. Kasich] to say something about the people who have been working for Meigs County for 25 years; they’re only making $12 an hour,” Mr. Smith said. “About people in this county who lost their careers when the coal mines closed.”

Neither he nor the other county commissioners have time for politics, he said.

“We’re not too much worried about what’s going on with President Trump and Russians and everything else, and trying to have an opinion about that, than what’s going on in Meigs County,” said fellow county commissioner Tim Ihle. “I don’t even know a Russian.”