After long wait, McMaster to join hall of fame

4/29/2008

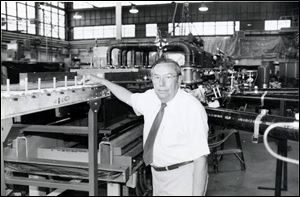

Harold McMaster in 1994 on the shop floor at Solar Cells Inc., which laid the groundwork for the founding of First Solar Inc.

Some inventions are the result of serendipity, a happy accident. The inventor instantly realizes the bonanza and shouts, "Eureka!"

But in the real world, it seldom happens that way. Useful inventions typically result from years of research, hard work, and trial-and-error testing.

So, perhaps it's fitting that it has taken many years for some highly successful Toledo inventors to be inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame in Akron.

Finally, this Friday evening, there will be five Toledo glass pioneers in the hall of fame that for many years had none. The latest inductee will be the late Harold McMaster, who is being recognized for his glass-tempering equipment that is in global use. He died in 2003 at the age of 87 and has more than 100 patents in his name.

He joins Michael J. Owens, inducted last year, who perfected the automatic glass-blowing machine in 1903 after six years of work and many failed attempts. And three men are there whose seven years of research in the 1930s led to the development of fiber-glass and to the formation of Toledo-based Owens Corning. Dale Kleist, Russell Games Slayter, and John "Jack" Thomas were inducted posthumously in 2006.

Mr. McMaster will be memorialized for the equipment that produced tempered safety glass, the type that has no sharp edges when broken.

But the plaque in Akron won't do total justice to the man who will be regarded as a solar-energy pioneer, who developed several life-saving military-aircraft improvements in World War II, and who donated many million of dollars to northwest Ohio universities (including the University of Toledo and Defiance College).

Even though he was at times able to get glass machinery from design phase to production in mere months, it took decades for his ideas to come to full fruition.

And, like many another prolific inventor, he died without fulfilling all his dreams.

Mr. McMaster, born into a family of 13 children in Deshler, Ohio, was inventive even as a youngster and fashioned a threshing machine and a hay loader.

A year after he got his master's degree in physics and astronomy from Ohio State University in 1939, he was hired by Toledo's former Libbey-Owens-Ford Co. as a research physicist and later became manager of its optical glass laboratory.

During World War II, he developed a system, still in use, for de-icing aircraft windshields, a rear-vision periscope for fighter planes, and technology for bending windshields for bombers. Some of that technology lent itself well to auto-glass production after the war.

In 1948, Mr. McMaster became a founder of Permaglass Inc., a Millbury firm that later became part of Guardian Industries, of Detroit.

Within a decade, his glass furnaces designed for Permaglass had evolved from televisions to automotive uses, and in 1971, along with Norman Nitschke and Frank Larimer, he co-founded another firm, Glasstech Inc., in Perrysburg.

That firm manufactured glass-bending and tempering machinery and had customers around the globe.

In time, Mr. McMaster probably will be regarded as a solar-energy pioneer, too.

He started thinking about solar power in the early 1970s and began investing in solar energy in 1984.

One of his companies, Solar Cells Inc., helped form First Solar Inc., of Tempe, Ariz., a firm with $22 billion in market capitalization. First Solar's only North American panel factory is in Perrysburg Township.

Mr. McMaster was able to stay focused on his goals, even if they took decades to achieve.

"He was the most tenacious man I ever met," said Mike Cicak, a longtime executive for several McMaster companies. "He was way ahead of his time."

His widow, Helen McMaster, recalled that "he was thinking all the time. He always said, 'There has to be a better way.'•"

Despite his many successes, Mr. McMaster didn't get all he wanted.

His revolutionary rotary engine never proved workable (at least during his lifetime).

He also was unable to advance some ideas about physics.

He believed Albert Einstein's Theory of Relativity was flawed and needed some additional input, especially from Mr. McMaster's own theories of gravity and outer space.

"He always said he wished he could argue with Einstein," said Mrs. McMaster.