DAY 4: Demons of past stalk Tiger Force veterans

10/22/2003

Therlene Ramos visits the grave of her son, Sam Ybarra, at a cemetery on the San Carlos Apache Reservation in Arizona. After returning from Vietnam, Ybarra drank for days at a time. `He was alive, but dead,' she said.

Morrison / Blade photo

For Barry Bowman, the images return at night.

The elderly man praying on his knees. The officer pointing a rifle at the man's head.

The shot.

That piercing shot.

Before it's over, the old man drops to the ground - his body twitching in the blood-soaked grass.

Over and over, Mr. Bowman relives the execution of the Vietnamese villager known as Dao Hue.

Despite years of therapy, the former Tiger Force soldier is still deeply troubled by the brutal shooting he witnessed as a young medic in the Song Ve Valley.

He's not alone.

Of the 43 former platoon members interviewed by The Blade in an eight-month investigation of Tiger Force, a dozen expressed remorse for committing or failing to stop atrocities.

They share some of the same symptoms - flashbacks or nightmares - and over the past 36 years have sought counseling, they said.

Nine have been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD, a psychiatric condition that can occur following life-threatening experiences.

To this day, they wrestle with memories of Tiger Force's rampage through more than 40 hamlets in the Central Highlands of South Vietnam in 1967.

Mr. Bowman, who was standing next to Mr. Dao when he was shot to death by a platoon leader, said he remains shaken by the unprovoked attack on the 68-year-old man as he prayed for mercy.

“It was devastating,” he said.

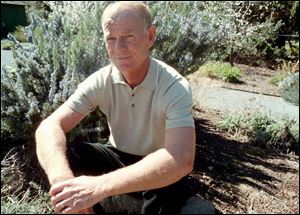

Rion Causey, a former Tiger Force medic, says he participated in group conseling a decade after seeing the killing of villagers in Vietnam. 'I didn't condemn what was going on at the time. I was 19 years old, but I knew what they were doing was wrong.'

For many, the images never fade.

When Douglas Teeters closes his eyes, he sees villagers being shot as they wave leaflets that guaranteed their safety.

He takes anti-depressants and sleeping pills, but he can never seem to get enough rest, he said.

Mr. Teeters is among the one-in-six Vietnam veterans - about 500,000 - who have been treated for PTSD.

Most people who overcome the disorder are able to recall horrific events without feeling the trauma. The frequency of nightmares decreases while patients gain more control over their lives.

But it can be more complicated for those who committed - or failed to stop - atrocities, clinicians say.

In addition to the trauma, they are often saddled with a strong sense of guilt that can complicate the deeper feelings of fear and isolation, says Dr. Dewleen Baker, director of a PTSD research clinic in Cincinnati.

“It's another layer that needs to be addressed,” she said. “It's not that easy. How do you reconcile killing civilians? It's hard, especially when you have a core set of values.”

Sometimes, patients will vacillate between justifying their acts and condemning what they did, said Dr. David Manier, a psychology professor at the City University of New York who treats veterans for PTSD.

When the attacks on villagers are executions - not shootings in the frenzy and confusion of battle - “it makes it more difficult to make sense of things,” he said.

Mr. Teeters said he struggles with his own acts - the executions of captured soldiers - and the actions of former platoon members in the deaths of villagers.

“The killing haunts me every minute of my life,'' he said in a recent interview. “To survive, you had to say, `The killing don't mean nothing.' That's how you got through it, man. But eventually, it all catches up with you.''

Former Sgt. Ernest Moreland refuses to talk about his role in the stabbing death of a detainee near Duc Pho, saying he fears he could be charged. But he said he still tries to rationalize the killing.

“The things you did. You think back and say, `I can't believe I did that.' At the time, it seemed right,” he said. “But now, you know what you did was wrong. The killing gets to you. The nightmares get to you. You just can't escape it. You can't escape the past.”

He is among nine of the veterans interviewed who said they turned to drugs or alcohol to ease their pain after returning from Vietnam.

“I drank too much. I got into a lot of fights,” said Mr. Moreland, who now lives in Florida.

It wasn't until four years ago that he sought help. “I came very close to committing suicide,'' he said.

Another platoon soldier, Sam Ybarra, often drank for days at a time, rarely leaving his trailer in Arizona, said his relatives.

While he showed classic symptoms of PTSD, with long bouts of depression, he died in 1982 before being diagnosed. In the years after the war, he expressed remorse for killing civilians, said his mother, Therlene Ramos, 78.

“He drank to forget about what he did,” she said. “He was a normal person before he went to Vietnam. When he comes back, he was an alcoholic, smoking. He was not the same person. He was alive, but dead.”

Looking the other way

takes a toll on veterans

Several veterans said that by the time they joined Tiger Force, the unit was steeped in practices that violated Army regulations and international law.

To survive, they felt they had to look the other way.

One of those was Rion Causey.

The 55-year-old nuclear engineer said he participated in group counseling a decade after witnessing the killing of villagers northwest of Chu Lai. “I was waking up at night with the sweats,” he said.

“I didn't condemn what was going on at the time,” said the former medic. “I was 19 years old, but I knew what they were doing was wrong. It was wrong.”

Two others said they are remorseful for standing by while platoon members took out their aggressions on villagers.

“I regret not reporting it,” said former medic Harold Fischer, now 54. “I was young. I didn't know any better.”

Now living in Texas, he was with Tiger Force during the military campaign near Chu Lai. He said he knew the slaughtering of civilians was morally wrong but feared retribution from platoon members for speaking up.

“We had to live with these guys in the field,” he said. “They're armed and dangerous and motivated. They have a lot of testosterone. They're young. Who knows what they would do? You get into a firefight and you may get a proverbial `To whom it may concern round.'''

Several former platoon members said they went through stages - at first disturbed by the brutality against unarmed villagers and then ignoring it. Eventually, they admitted to taking part in war crimes.

Barry Bowman, now living in Rhode Island, said he joined Tiger Force to save lives.

In one of the atrocities investigated during the Army's 41/2-year inquiry, he refused a sergeant's order to kill a wounded prisoner in the Song Ve Valley. But four months later, he said he didn't hesitate to kill an injured villager dressed in the gray robes of a Buddhist worshipper.

“It was against everything I stood for,” he recently said. “My basic mission was to save people's lives as a medic and I took it that way. But then, I could steadily see that the longer I stayed in combat, the more that was changing.''

A culture existed in Tiger Force that embraced the executions of prisoners and civilians - one encouraged by officers and sergeants.

One former sergeant now being treated for PTSD said he wanted his men to kill without hesitation.

“It didn't matter if they were civilians. If they weren't supposed to be in an area, we shot them,” said William Doyle, 70, of Missouri. “If they didn't understand fear, I taught it to them.”

He said he and others also cut off the ears of numerous dead Vietnamese to scare enemy soldiers.

Experts say body mutilations are classic symptoms of soldiers in secondary stages of PTSD in which fear turns into anger, said Dr. Baker, who treats veterans at the Cincinnati Veterans Affairs Medical Center. “They kick into a second stage - a rage mode.”

Former platoon medic Joseph Evans, who lives in Atlanta, said in a recent interview that he severed ears. “You fall into this unbelievable frustration,” said Mr. Evans, 59, who has been treated for PTSD. “You're burned and you're fried and you're scared, and you do it to make light of the burden you're underneath.”

Former soldier says

he wants to apologize

William Carpenter said before he dies, he wants to return to the Song Ve Valley.

The 54-year-old former platoon specialist wants to go to the rice paddy where Tiger Force soldiers killed four elderly farmers.

He wants to apologize to their families.

Thirty-six years later, he said the assault on 10 farmers remains a vivid memory. “I want to tell them how sorry I am that it happened,” said Mr. Carpenter, of Rayland, Ohio, who has been treated for PTSD.

Experts say one way of coming to terms with the disorder is to openly acknowledge past actions.

Mr. Carpenter said he didn't fire on the farmers but never reported the atrocity to commanders.

Like other former Tiger Force members, he said he can justify many of the aggressive acts toward villagers, but he said it's “in the middle of the night when the demons come that you remember. That you can't forget.”