Unit's founder says he didn't know of atrocities

3/28/2004

As a young officer, David Hackworth receives the Silver Star from Gen. Omar Bradley for heroism under enemy fire in Korea on Feb. 6, 1951.

COURTESY HACKWORTH

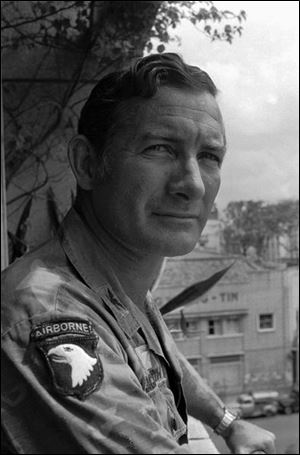

Col. David Hackworth in 1971 at the time of his critical remarks on the conduct of the Vietnam War.

A day after enemy soldiers had nearly overrun his base camp, the commander of one of the most battered and bloodied battalions in Vietnam prepped his elite platoon to hunt down their attackers.

In a 1966 pep talk laced with obscenities, the commander said he wanted 40 "hard charging" men, and anyone who couldn't be "hard charging" would be kicked off the special team.

The men did not let their commander down as they took the fight to the enemy, endured heavy casualties, and earned a coveted mention in a presidential unit citation.

But, within a year, that elite platoon - known as Tiger Force - would go on to hunt more than the enemy. Some soldiers would turn their rifles on hundreds of unarmed men, women, and children in what became the longest known string of atrocities by a U.S. battle unit in Vietnam - crimes that would be hidden by the Army for more than 36 years until revealed last fall by The Blade in its series Buried Secrets, Brutal Truths.

And Tiger Force's founder, David Hackworth, would go on to his own fame.

He would become the Army's youngest colonel in Vietnam at age 40, collecting an impressive array of battle decorations but also breaking rules as he saw fit - once running a brothel for his troops and smuggling gambling winnings out of Vietnam.

He would speak out against the Army leaders who ran the war, but then rely on them to let him retire and avoid a court-martial.

And, decades later, he would gain his most fame as a best-selling author, war correspondent, and syndicated columnist to 10 million readers a week - with supporters lauding him as a courageous whistleblower even as critics consistently questioned his integrity.

A rags-to-riches writer who now lives in a wealthy Connecticut enclave, Colonel Hackworth remains as outspoken as ever - bashing the Bush administration's handling of the Iraq war and now saying "war is an atrocity."

But the 73-year-old is leery to talk about the shadow that's been cast over the once-celebrated unit that he helped create.

A man who repeatedly touted Tiger Force as a model for fighting guerrilla wars is unwilling to speculate about what caused the unit to spin violently out of control - leading to a series of war crimes in the Central Highlands of Vietnam in 1967, whose revelation has prompted the Army to open a rare review of a long-closed case.

Promoted out of Vietnam before the platoon began its string of atrocities, he now says he had no idea that the unit he once considered "my boys" had later committed crimes that became one of America's dark secrets of the war.

As a young officer, David Hackworth receives the Silver Star from Gen. Omar Bradley for heroism under enemy fire in Korea on Feb. 6, 1951.

David Hackworth recalled "walking on air."

On Feb. 7, 1966, the 35-year-old Army major was given control of a task force - named after him - to rescue a company of soldiers pinned down by the enemy.

It was the first time he would orchestrate a battle in Vietnam, and the natural career progression of a Southern Californian orphan who had already turned heads in the Army.

Raised by a grandmother and foster parents, he sneaked into the Army in 1946 at age 15, survived four battle wounds in Korea, and earned a Silver Star there for heroics. The gangly grunt had impressed commanders so much they awarded him a battlefield commission to second lieutenant and gave him control of his own commando unit.

Four months before the formation of his task force in Vietnam, Major Hackworth had become second in command of the 101st Airborne's 1st battalion/327th Infantry Regiment. A month later he helped create Tiger Force - modeled after his commando unit in Korea.

It was a new kind of war, where large units were sitting ducks, and Tiger Force would be a new kind of unit, one that would break into small teams and head deep into dangerous territory to "out-guerrilla" the guerrilla fighters. And it would be the emergency responders to help out bigger units in trouble.

Major Hackworth called on his emergency responders that February afternoon at My Cahn. It would become the young unit's bloodiest battle to date - helping create the heroic image of the Tigers, as well as lead to some sore feelings years later among former soldiers of the platoon.

He ordered Tiger Force's commander, 1st Lt. Jim Gardner, to attack across a river into what he thought was a small unit of enemy soldiers. The Tigers affixed bayonets on the ends of their automatic rifles, forded a river, and charged the North Vietnamese.

The mission did not go as planned. The communists had plenty of manpower - concealed in well-defended positions - and began mowing down some Tigers and pinning down others. Major Hackworth radioed to the lieutenant, demanding more action. Moments later, Lieutenant Gardner was killed after hurling grenades into enemy bunkers before the rest of the team made it back to U.S. positions.

Years later, it would lead to feelings of guilt for Colonel Hackworth, who would write in his best-selling 1989 autobiography, About Face, that "when someone dies for you ... it's the worst of all crosses a combat leader has to bear."

By the time the battle was over, nearly every member of Tiger Force had been killed or wounded. Lieutenant Gardner was awarded the military's highest award, the Medal of Honor, posthumously.

Major Hackworth, uninjured in the battle, was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross - the Army's second highest honor - for putting himself in harm's way as he planned and oversaw the battle, according to the award's notation.

Just how many Tiger Force soldiers deserved awards, and didn't get them, has been a sore subject for decades.

Military author Robert Lynn, who wrote about the battle in a 1990 article in Vietnam magazine, said former platoon soldiers he interviewed then were still upset.

"When these awards and decorations were made only to individuals that were in Hackworth's circle, the other members of Tiger Force felt shafted and cheated," Mr. Lynn recalled recently.

In an e-mail to The Blade last week, Colonel Hackworth said his subordinates, not him, would have been responsible for submitting award notifications through the chain of command.

"One thing I can tell you about awards is that the system is terribly unfair and frequently heroes go unrecognized because the paperwork is lost or their actions did not have the proper witnesses," he wrote.

After the battle at My Cahn, fresh faces seeking adventure rushed to fill the slots of soldiers who died, were injured, or completed their one-year tours.

And Major Hackworth continued shepherding the unit.

By June, 1966, he had become the commander of the 1st battalion/327th infantry before a major battle near Dak To, when the enemy overran the U.S. base camp.

Colonel Hackworth recalled last week that the night of the attack the Tiger Force commander had disobeyed an order to set up an ambush of retreating enemy soldiers - prompting then-Major Hackworth to relieve him and setting the stage for his fight-or-get-out pep talk the next day.

That was the day that Washington Post reporter Ward Just came to see the respected battalion and quickly grew to admire the major.

"He was always looking for a fresh solution," recalled Mr. Just, now an author.

Tiger Force was considered that solution, and Mr. Just wrote about the pep talk and the unit's battlefield heroics in his 1967 book To What End.

He would also mention in his book something one of the troops had told him: That a Tiger Force soldier regularly cut the ears off enemy dead and mailed them to his girlfriend - a clear violation of the Geneva Conventions.

More than three decades later, Colonel Hackworth said last week he had never heard of the allegation and suspects the story was "a 19-year-old's bravado for the ears of a Washington reporter."

Weeks after the famed battle at Dak To, Major Hackworth was promoted to a lieutenant colonel and started a job in the Pentagon's personnel section.

And Tiger Force would go through a succession of commanders and soldiers. By May, 1967, the documented string of war crimes would begin with a soldier cutting the ears of a dead enemy soldier. The carnage evolved into soldiers targeting unarmed men, women, and children.

According to U.S. Army investigative records and interviews by The Blade of dozens of former Tiger Force soldiers, members of the platoon are estimated to have killed hundreds of non-combatants.

Former soldiers who witnessed the atrocities blame commanders who either weren't paying attention or inflamed the passions of soldiers with demands for enemy "body count" - at the same time offering inconsistent directives on just who was deemed "the enemy." Records show at least three soldiers complained to superiors about the war crimes, but the Army did nothing to stop them.

Looking back on the unit's descent into war crimes, Mr. Just believes the hands-on commander he had come to respect may have been able to avert the unit from crossing the line.

Colonel Hackworth won't speculate on the causes of the downward spiral of the unit.

"If you were not there," he said recently, "you simply cannot judge."

But he has seen war crimes first-hand. Once as a sergeant in Korea, one of his soldiers executed four prisoners after making them dig their own graves. Then-Sergeant Hackworth kicked the man out of his unit but didn't pursue charges, saying in About Face that no one reported war crimes there because "all of us had seen too many atrocities, and what is war anyway but one raging atrocity?"

Still, he has been willing to criticize those involved in the Vietnam War's most notorious atrocity, at My Lai, and the cover-up that ensued.

He has said the March, 1968, massacre that killed more than 500 villagers was an indictment of an Army leadership corps that consistently rotated itself to pad officers' resumes - and cared more about protecting their jobs than righting wrongs.

And last December he told the New York Times that the Vietnam War "was an atrocity from the get-go" and "there were hundreds of My Lais."

It was a controversial statement. Academics have long disputed just how many unknown atrocities occurred in Vietnam, but most scholars agree that the majority of soldiers in Vietnam did not commit war crimes. And no other single event of the war has surfaced to compare to the 4 1/2-hour rampage that occurred in the cluster of villages commonly known as My Lai.

When asked what he meant about there being hundreds of My Lais, the retired colonel told The Blade last week he was using a broad definition of war crimes.

"Every U.S. bomb or rocket that struck a city or a village killing non-combatants was a war crime," he said. "Who investigated this?"

The Tiger Force case would become the longest investigation in the history of the Vietnam War - from 1971 to 1975.

But, like all of the battalion commanders who'd left before 1967, Colonel Hackworth would not be among those questioned.

Still, just as the Tiger Force case began, the colonel squared off with Army investigators about his own problems.

He had spoken out against the war in June, 1971, prompting the Army to look into his background. They discovered a host of rules violations but did not court-martial him - instead letting him quietly retire to Australia, where he would run a restaurant, protest against nuclear war, and be awarded a United Nations Medal of Peace.

He wouldn't gain fame again back home until About Face came out in 1989 and he returned to America a celebrated war hero.

His dark hair has gone white. He's been slowed by age. The gangly teenager who wanted only to be a career soldier has now spent more years out of the Army than in it.

But Colonel Hackworth remains engaged in thoughts of war. From his home in upscale Greenwich, Conn., he writes a weekly syndicated column and operates a Web site - www.hackworth.com - for supporters to offer tips, learn his views, and buy his books.

The man who prefers to be called "Hack" may not want to talk about the troubles of his former unit, but he is quick to lament the loss of life in the latest war.

"Who's writing about the thousands of Iraqi civilian dead and wounded as [a] result of U.S. firepower during and after our operations in Iraq?" he said last week.

With a second Distinguished Service Cross and nine more Silver Stars, Colonel Hackworth has the clout to write about America's latest war - even if he has repeatedly fought questions over his own integrity in the last decade.

In 1996, as a Newsweek columnist, he readied a story about how the Navy's top admiral wore two unearned awards for valor - prompting the admiral to shoot himself even though he insisted he had made an honest mistake.

After the colonel insisted "there's no greater disgrace than wearing unearned valor awards," the U.S. Army Ranger Association complained that Colonel Hackworth was falsely claiming to have earned a "Ranger Tab" - the decoration commonly given to those who graduate from elite Ranger special forces training.

The Army concluded that the colonel's military personnel records mistakenly showed he'd earned the award when there wasn't proof. He insists he earned the award and has witnesses to prove it.

Six years later the ranger association still believes the colonel's explanation of how he earned the award "is simply not a credible story," according to association executive vice president Steve Maguire.

Colonel Hackworth has been able to win some battles. A former Army peer once accused him of making a major blunder in a key Vietnam battle, but a December book cleared the colonel and pinned the blame on someone else.

Still, detractors remain.

Some shake their heads at the colonel's outspoken bias against homosexuals - he once said there were no "greater liars or greater deceivers than gays."

Others complain he exaggerates problems to woo sympathy and supporters - a 1996 article in Slate Magazine called him a "major embarrassment" to journalism.

Colonel Hackworth remains undeterred.

More than 30 years after he left the battlefields of Vietnam, the war hero insists he's still looking out for the grunts left to fight a poorly planned war with substandard supplies.

"I am 73, and over the years I have seen too many soldiers pay a dear price for military incompetency."

Contact Joe Mahr at jmahr@theblade.com or 419-724-6180.