Detroit exhibition spotlights works by Rodin and Claudel

12/4/2005

<i>The Waltz</i>, by Camille Claudel.

<i>The Waltz</i>, by Camille Claudel.

At 17, Camille Claudel (1864-1943) was a gifted student of sculpture; determined and strong-willed, beautiful and erratic. A bronze head she made of an elderly woman, with jutted jaw, wrinkled forehead, and tidy bun, had remarkable detail and expression.

It was 1881. A French feminist newspaper was calling for changes to the outdated Napoleonic code. Victoria was queen of England. And in the United States, Susan B. Anthony published the first volume of History of Woman Suffrage.

When young Claudel met Auguste Rodin (1840-1917) in Paris, he was 41. An ambitious star rising toward an extraordinary apex in both the art world and the lively Parisian social scene, he was winning major commissions.

At 18, Claudel shared a studio with other women artists and exhibited at the Salon des Artistes Francais, listing Rodin as one of her teachers. The next year, he hired her as a studio assistant.

The ardor they had for each other was intensified by their shared passion for art. He made sculptures of her face - petite, delicately featured - in terra cotta, bronze, and pate de verre (a glass paste). She created a large, dignified bronze bust of him, so flattering that he declared it his official portrait.

In this intimate frame of reference, 130 of their works are displayed in "Camille Claudel & Rodin: Fateful Encounter," at the Detroit Institute of Art through Feb. 5. The 15 galleries include dozens of photographs and letters, and an entertaining recorded audio tour is included in the price of admission.

It's the first time their works have been shown side-by-side in the United States, and the emotional, sensual exhibit brings new prominence to Claudel.

Initially, she learned from the master. He said she understood his work as no one else did, and he consulted her on aesthetic decisions. Their plaster works mingled in his busy studio, resulting in some of her pieces being attributed to him.

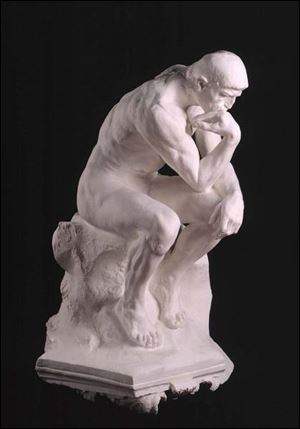

Rodin's most famous creation is <i>The Thinker</i>, a copy of which stands in front of the Detroit Institute of Art.

Rodin would be called the greatest sculptor since Michelangelo; the man who propelled dimensional art from Romanticism to modernity and abstraction. He loved wealth, parties, adulation, and much-younger women, who were often his studio models. Overseeing a shop of employees who carried out his designs - molders, stone cutters, carvers, and bronze finishers - he amassed a huge body of work, for which his staff kept meticulous records. And he ensured his legacy by willing everything to the French government for a Rodin museum.

Claudel, however, had scant appetite for parties and schmoozing. She had no studio, no staff, and did all her own work. Rarely undertaken by women, stone and bronze work was heavy and physically difficult. But she was compelled to sculpt, and expected to have as much freedom as her male counterparts.

Her art was invariably compared to Rodin's, and before long, she felt overshadowed. She distanced herself from him, and at 22, went to England for four months. Rodin followed her, but she refused to see him. To win her affections, he wrote a contract promising to help her artistically, take her on a long trip, and make her Madam Rodin.

Claudel came back, but Rodin would not sever ties with Rose Beuret, a studio model he met the year Claudel was born. Rose stuck with Rodin from his unknown days through his infidelities and she raised their out-of-wedlock son who was mentally retarded. Rodin never acknowledged the boy, but usually lived with Rose. In 1917 when they were in their 70s and Rose was a few weeks from dying, he married her.

By her 30s, Claudel had given up on Rodin. She retreated into a shell layered with paranoia and became a hermit. When she was upset, she smashed her art and hurled it into the fire. She struggled financially. She suspected Rodin was out to get her. She suffered from schizophrenia.

A week after her protective father died, her brother and her mother, who never forgave her for her affair with Rodin, hired two men to forcibly haul her to a mental institution and ordered that she have no visitors. She was 48. She tried valiantly to get released but didn't succeed. She never made art again, and 30 years later, she died of starvation during World War II.

Aiming to reveal the influence of Claudel and Rodin on and reactions to each other, this show is divided into three broad groups: their art before they met (mostly clay figures by Claudel); work produced during their happy and then stormy years together, and finally, their sculptures after the breakup.

Humble but especially appealing are the almost crude plasters and clay pieces they fashioned, trying out different looks; their daubs and pinches are visible.

Rodin's larger-than-life 1880 bronze of the lean, striding St. John the Baptist, has meticulous anatomical detail. "All I did was copy the model chance had sent me," he wrote about the physical perfection of the Italian peasant who spontaneously struck the pose Rodin captured.

"I consider that the body is the only true clothing for the soul, that allows its radiance to shine out," he said. Ironically, his skill at realistic rendering of the human form had wrung accusations from critics who suggested that he made body casts of his models.

Rodin began by sketching on paper and then making several versions in clay or plaster. He molded and cast figures in the nude and in a second phase, clothed them. When he was satisfied with a final plaster, he delegated the execution to his staff, supervising closely.

Rodin is most famous for The Thinker, a copy of which stands in front of the Detroit museum. Representing the Italian poet Dante, The Thinker was originally a little figure at the top of a plaster Rodin made for The Gates of Hell, massive doors that were intended for a new museum of decorative arts in Paris. The doors, a plaster portion of which is displayed, included hundreds of figures in low relief, inspired by Dante's The Divine Comedy.

The museum was never built, but with the commission, and another for the huge The Burghers of Calais, he expanded his shop and hired Claudel.

Conceived during their happiest years, his Eternal Spring and The Kiss, were nude couples locked in elation.

Claudel worked long hours in the studio on Rodin's projects and some of her own, but was bucking for independence. Moreover, she was gradually realizing that Rodin might not leave Rose.

When she was 23, he rented her a studio and she began the bust of Rodin and her early masterpiece, The Waltz, in which a couple rises out of a chaotic swirl into tender embrace. Exhibited in 1893, it was more graceful and no more erotic than Rodin's well-received nudes, but a potential buyer for the French government advised her to add a measure of modesty to the figures. She complied, encircling the pair with a fire-like shawl.

Most painful are Claudel's anguished pieces, notably The Age of Maturity, in which a man is held by a skeletal crone on one side and reached for by a young woman on the other. Rodin recognized it as himself, Claudel, and Rose, and was furious. When her government commission for the piece was revoked, Claudel believed the powerful Rodin was to blame.

A stunning piece is Rodin's giant plaster monument to Balzac, the prolific French author who died in 1850. The figure is a leap toward abstraction. It is corpulent and clad in the monk's robe Balzac wore when he wrote. Rodin built exaggerated realism into Balzac's over-emphasized head, with a lion's mane of hair, deep-set eyes, and a heavy brow. Claudel wrote Rodin a rare letter, saying it was wonderful. But when the plaster model was exhibited in 1898, it was ridiculed by the public and rejected by the organization that had commissioned it. Deeply hurt, Rodin took it home and refused to have it cast into bronze. After that, he would not finish public commissions.

The Balzac was cast years after Rodin's death.

Working and living in solitude, Claudel had a female benefactor for some years for whom she made beautiful marble busts. She also created small-scale pieces, intimate poems she called "sketches from nature." The Wave, inspired by the same Japanese print that motivated Debussey to compose La Mer, was worked from the hard-to-carve marble/onyx. She modified some of her earlier figures into beautiful pieces, carving with remarkable virtuosity and polishing to extraordinary sheen.

As Rodin and some others were minimizing detail in their sculpture, Claudel headed, in the spirit of the times, toward art nouveau, said Line Ouellet, author of "Camille's Exile, Rodin's Glory," an article in the book that accompanies the exhibition. Some of Claudel's later pieces had the feel of decorative arts, Ouellet added. They may have lacked innovation, but they were beautiful.

This show was organized by the Musee national des beaux-arts du Quebec, in conjunction with the Musee Rodin in Paris. Staff at the two museums got to know each other when they organized the 1998 "Rodin in Quebec" blockbuster show, which drew an astounding 524,273 visitors.

The Quebec museum wanted another Rodin exhibit, and when the Musee Rodin planned to close for renovation this year, arrangements were made to empty its Claudel collection. The Paris museum did not close after all, but dozens of promised pieces were boxed and shipped, said Ouellet, director of exhibitions and education at the Quebec museum. During its three-month summer run in Quebec, the exhibit had 186,425 visitors, she said.

After Detroit, the show travels to its final destination, Martijny, Switzerland.

"Camille Claudel & Rodin" continues through Feb. 5 at the Detroit Institute of Art, 5200 Woodward Ave. A lecture, Camille Claudel: Instinctive Rebel, by Odile Ayral-Clause, author of "Camille Claudel: A Life," will be Sun. Jan. 29 at 2 p.m. Exhibit tickets are timed and include an audio tour. Hours are 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Weds. and Thurs.; 10 a.m. to 9 p.m. Fri., and 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Sat. and Sun. The week of Jan. 30, days and hours will vary. Adult tickets are $14 during the week and $17 on weekends. Tickets for children are $8. Tickets purchased by phone and online have an additional $3.50 per ticket charge. Information: 1-313-833-7971 and www.dia.org.

Contact Tahree Lane at: tlane@theblade.com or 419-724-6075.