Find out what's new at the Toledo Museum of Art's latest show

3/7/2009

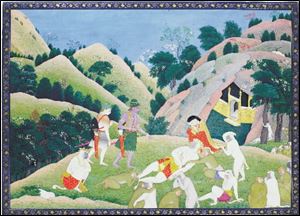

'Death of Bali,' 18th century Kangra style, India.

For more than 50 years, the museum waited.

Someday it would round out its group of 18th-century French paintings with a canvas by the marvelous Jean-Simeon Chardin (1699-1779).

Chardin, beloved in his native Paris, crafted still lifes, portraits, and domestic scenes with stunning realism a century before photography was invented. Through the decades, the museum considered, but rejected, several Chardins it believed to be second rate.

"We wanted to get it right," explained curator Larry Nichols.

Six museum directors later, in March, 2005, Nichols got a tip: a colleague had seen a pristine pair of Chardins, owned by one family for more than 200 years, for sale in Paris. In one, a woman leans into a sudsy laundry tub. In the other, a woman draws water from a copper cistern. Nichols flew to France, had the paintings delivered to Toledo, and by years end, the jewels were Toledos.

Since its centenary nine years ago, the Toledo Museum of Art has bought or been given more than 1,100 objects. Nearly half are displayed in a free exhibit, Look Whats New? The Second Century of Collecting at the Toledo Museum of Art, through May 31.

Enter the second-floor Canaday Gallery and instead of a carefully plotted tableaux, youll face a partial wall with nine pairs of holes at varying heights. Peek through any "binocular" and youll see one of three art works acquired since 2001 and dating to the 18th, 19th, or 20th century.

The four women and two men who comprise the museums curatorial staff scrutinized their records and recommended objects for this show, a logical follow-up to last years Mummies to Monet: The Libbeys Collect, that focused on items donated from 1906 to 1916 by museum founders Florence and Edward Libbey. Another in this ongoing series of home-grown exhibits was 2004s successful The Unseen Art of TMA: Whats in the Vaults and Why?

Look Whats New has two goals: to display these objects, many not exhibited before, and to explain how and why they were brought under the museums roof, said Nichols, who organized the endeavor with Jutta-Annette Page, curator of glass.

"Im excited about having visitors see the playful positioning of things: sometimes theres a reason, sometimes theres not," said Nichols, the William Hutton Curator for European Painting and Sculpture before 1900.

Consider, for example, this siting: A glass case holds a wooden monkey, hands covering its ears in hear-no-evil fashion. It was carved in China about 200 B.C. Is the monkey shunning its hefty case-mate, a tangle of rusty steel angles cast in 1971 by Greek-born Lucas Samaras?

Or is the simian shocked by the anti-Darwinian painting a jump away? In this 1891 oil by Ohioan William Holbrook Beard, seven nattily dressed monkeys puzzle over an odd turtle, its shell inscribed with "200,000 B.C. Adam." In Discovery of Adam, Beards monkey-men are confounded to realize their forebear is not a human creation of God but a lowly reptile.

With 300 items (including 140 art marbles), the butter-cream walls of the Canaday enfold the bulk of the exhibit. A brochure provides maps of where to find other items in the Works on Paper Galleries, the Glass Pavilion, the outdoor Sculpture Garden, and elsewhere.

A fun idea is just outside Canaday Gallery 18 where the newest goods, those acquired yesterday, today, and tomorrow will be placed.

Objects in Canaday are organized according to year acquired, with colored banners introducing each year and matching colors on individual labels. Roy Lichtensteins cows, morphing from representational to abstract in a series of six, arent far from a 16th-century landscape.

A look-it-up computer lists all of the museums 21st-century acquisitions by medium, artist, and year.

Storytelling is key to understanding the how and why, and a couple of short videos and an audio phone help. In text panels, curators explain why a particular item fills a gap (such as the Chardins) and discuss donations.

Best of all, curators and invited experts will speak at seven free Friday evening talks between now and late May.

In one text panel, Amy Gilman describes a fast decision to pick up a painting that had been in private hands for 76 years. Gilman, associate curator of modern and contemporary art, was walking through the Art Basel Miami Beach fair in late 2007 with museum director Don Bacigalupi when they turned a corner and were struck by what they saw in an alcove: a 1931 Paul Cadmus portrait of his then-lover, painter Jared French. Owned by Jared French and his heirs, it was for sale for the first time. Gilman and Bacigalupi had previously talked about acquiring a Cadmus, and snapped it up.

Going to art fairs such as the contemporary Art Basel is an efficient way for curators to check out a vast array in one place. Moreover, they network, chatting with dealers, colleagues, and gallery staff with whom they or the museum may have long-standing relationships.

"Donations by generous local donors allow me and other curators to attend these fairs," wrote Carolyn Putney, curator of Asian art, in a text panel.

It was at an Asian art fair in London in 2007 that she found what shed been searching for: an 18th-century Kangra-style miniature painting from northwest India.

Ms. Putney showed images of the miniature to Bacigalupi and asked the London dealer to ship it to Toledo, where it delighted the art committee.

"It is crucial for curators, the director, and the boards Art Committee to see a work in person, as the effect is often quite different than viewing it from a reproduction," she wrote.

The issue of conservation was vital in the decision to buy a 600-year-old painting, The Crucifixion, by Jacobello del Fiore.

"We need to understand the condition of the piece were considering," said Nichols. What shape is it in, and how will it hold up? What materials was it made from, and what techniques did the artist use?

Large and chromatically rich, The Crucifixion was painted on wood, which is organic and less stable than other materials. Some of the paint, such as a blue pigment derived from the mineral azurite that originally colored the robe of Jesus mother Mary, had blackened. A bit of silver leaf applied to armor and gold leaf in the haloes had also darkened. Museum staff decided not to repaint the blue, silver, and gold, figuring the darkened areas represented a natural aging process.

"Fortunately the paint surface in the main is remarkably well-preserved for a work of this material, age, and size," Nichols wrote in a text panel.

However, an inch-long gash in the lower left was filled and painted in such a way that it can be reversed should anyone want to reveal it in the future, he noted.

Not on the text panel is the interesting back story about how this piece came to Toledo.

Before Nichols went to Holland for the European Fine Arts Fair in Maastricht two years ago, he received a color transparency from Patrick Matthiesen, a London dealer who planned to show The Crucifixion at the fair.

"I had put out the word that I was looking for a Venetian gold-ground painting," Nichols said. "We have Italian paintings of this period from Florence and Sienna but we lacked anything from this period from Venice."

When Nichols got to the fair, he made a beeline for Matthiesens stand.

"I was enamored with the painting straightaway," Nichols said. "It was spectacular."

Sharing his enthusiasm was Bacigalupi, also at the fair. For the next six days, Nichols spent about 90 minutes sizing up the painting from various perspectives. He refrained from gushing that this was exactly what the museum wanted.

"You hold your cards pretty close to the table," he said. He did, however, make it clear that the museum would give it serious consideration, effectively putting a "hold" on it. Six months later, he flew to London for a second look. Meanwhile, he researched. He went to the Accademia Galleries in Venice. "I wanted to test its quality against the largest collection of Venetian paintings." He checked other del Fiore and contemporary paintings at museums in Paris, Berlin, and London.

Contact Tahree Lane at:

tlane@theblade.com

or 419-724-6075.