The Art of Geometry: ‘Irregular Polygons’ by Frank Stella go on display Friday

4/3/2011

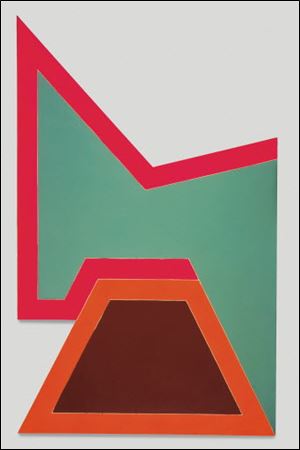

The band next to the triangle in 'Tuftonboro III' appears capable of propelling the triangle out.

STEVEN SLOMAN

Frank Stella said he thought 'Moutonville IV' would make a great building design.

It’s a triangle on a square; a parallelogram in a rectangle.

Simple geometry. But art?

You’ll decide if you like it. Before your final answer, freshen your eyes by expanding your visual vocabulary: it’s not rocket science, though rocket science certainly involves geometry, as does cabinet making, a cat’s cradle, quilting, building an automobile, and anything else that fits together.

Frank Stella will discuss his abstract geometric paintings with Toledo Museum of Art director Brian Kennedy at 6 p.m. Thursday in the museum’s Peristyle in a free talk moderated by writer Tyler Green. And beginning Friday, you can view the 11 monumental pieces Stella made 45 years ago when he was in his late 20s, a new father, and fresh from a year painting and teaching at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire. Frank Stella: Irregular Polygons, continuing through July 24, is in Canaday Gallery, transformed into a single large room hung with the giant dimensional cutouts. Admission is free.

"Visual literacy is the ability to construct meaning from images," said Kennedy. "I’m using Frank’s show to be the first in a series of building blocks to promote visual literacy."

Understanding Stella may be a challenging assignment for some.

The colors in 'Chocorua IV' create an illusion of depth.

These works were exhibited last year in the Hood Museum at Dartmouth, where Kennedy was director before joining the Toledo museum in September. Kennedy wrote an accompanying 2010 book, Frank Stella: Irregular Polygons, 1965-66, and Stella (who loves the book) suggested Kennedy bring the polygons to Toledo.

"Together the objects provide visitors a chance to engage with the ‘complex simplicity’ that is the paradox of Stella’s work," wrote Kennedy.

Asked about that ‘complex simplicity,’ Stella, in a telephone interview from his home in Manhattan, fired back with, "Who said that?"

Told those were Kennedy’s words, Stella, 74, said with a trace of humor, "Ohhh, Brian wrote it. Geez, And I’ve got to figure it out."

Sure it’s a triangle in a square, he said, and more if you take the time to see it.

"The basic idea of the geometry can be described in a relatively simple way: you can say ‘That’s a triangle stuck into a square.’ But it gets complicated when you look at it," said Stella. "There’s a lot of ways a triangle can fit into a square, and a lot depends on what you do with it. The idea can be fairly simple but the results can be quite different."

Symmetry

The word polygon, derived from the Greek, means many angles. A polygon’s number of sides is determined by the number of angles it has; its sides are of equal length and its angles are equal. In an irregular polygon, not all sides and angles are equal.

Kennedy suggests thinking about which shapes are emphasized in each piece and why. "When visitors go to an exhibition, they put themselves through a bit of a training course in the principles of art and design, harmony and disharmony, dependence and independence, color, shape, and line." Is there proportion?

The two shapes in 'Wolfeboro IV' abut each other.

Note the point, line, and plane. And check out equilibrium.

"I think you’ll see it," said Stella. Painter, sculptor, printmaker, and father of five, he is married to pediatrician Harriet McGurk.

"The paintings I made before the Irregular Polygons were very symmetrical geometry. And these [Irregular Polygons] are a geometry which is no longer symmetrical, but they have to be the same thing that symmetrical paintings are: they have to have a sense of equilibrium. They can’t fall over. There has to be a balance; they have to stand up. For the earth to keep spinning you have to maintain equilibrium. If the earth stops spinning it goes downhill and we’re in trouble. Equilibrium is everything: it’s true in painting as it is in everything else."

And consider tension between objects: some of the forms seem to push, some to resist; some appear about to soar, float, or be ejected with a spring-loaded quality.

"You can feel the forces of the pieces and the parts going together," said Stella. "Taking the simple example of the triangle being pushed into the square, the way these paintings are structured you can feel the triangle going into the square barrier. And it’s not like the triangle is overlapping, it’s not laying on top of it. You feel it pushing into it and penetrating it. And at the same time you feel the force of the triangle going in, you feel the force of the resistance in the rectangle. And there’s the possibility when you see the triangle going in there that the triangle’s going to be expelled. ... I like the quality of spring-loaded geometry."

Using color

Stella’s 11 canvases measure about 7-by-10-feet and larger, and are stretched on four-inch wooden frameworks. He replicated each piece four times, painting them differently to see how color would impact perception of the shapes.

Speaking of color: how do the three or four hues in each piece play off each other? Some sections are painted with fluorescent alkyd, others with industrial epoxy. Does color intensity or contrast add to the illusion of depth? If so, imagine the triangle as a pyramid inside a cube.

In 'Union I' a square in a truncated rectangle adds stability.

Suggesting movement are the eight-inch-wide bands surrounding shapes; areas without bands convey a different energy. A tiny pale line of raw canvas defines each band’s edge, the result of Stella’s use of industrial tape to separate sections he painted. The slightly jagged line (in which pencil lines can be seen) is the result of a paint-bleed that occurred when he pulled off the tape.

Artists, said Stella, should create a "habitable space" that’s attractive for viewers, encouraging them to spend time perceiving more than what they took in at first glance.

"I think it’s true of all kinds of pieces. It’s the way you end up thinking about Borromini or about any of the art of the past. It’s about looking at art and somehow you’re interested in it in itself and then you’re also interested in it as it relates to you. What does it allow you to think about?"

Consider also the distance or area between, around, above, and within.

"Space is a difficult problem in every way, not just for painting," he said. "The space we talk about in painting is not real space, it’s pictorial space; people have marked it and present it a way that you are to look at it. Probably you can’t see space. It’s the sense that you have of it; you can experience it without being able to see it."

‘A little bit nervous’

When Stella made this series, he had landscapes in mind.

"The abstraction is derived from places in New Hampshire. I’ve been to all of them; it was a landscape that I lived as a child," he said. "Geometry presents itself as interactive forms that could describe the landscape."

The band next to the triangle in 'Tuftonboro III' appears capable of propelling the triangle out.

Toledo is the first time he’s seen the complete series in one room. He flew in about 10 days ago to direct placement of pieces and the hanging height.

"I have to admit I’m a little bit nervous. I think of them as individuals or in pairs or smaller groups but I don’t see it all as one. It’s a horrible image, but it’s sort of like the team photo: the players [might] look better when they’re not in the team photo."

Stella was born in a Boston suburb in 1936 to parents who came from Sicily. His father was a gynecologist who liked to paint, his mother studied art and painted. He attended high school at the elite St. Phillips Academy where an excellent gallery focused on abstract art.

"From the very beginning when I was first making paintings in school, when we had an opportunity to do whatever we wanted and I saw pictures of abstract paintings, I knew. And you imitate things. And once I got started on that, it just worked for me, it was interesting. And opportunities presented themselves. I never ran into a brick wall. Or maybe I did a couple of times but actually the brick walls weren’t that strong. I knocked them down."

Stella employs one or two assistants in a large studio where he fashions plastic and foam into sculptures, takes photos, and scans them into a computer where he moves parts around. The final design is sent to a workshop in Belgium where the sculpture is built to his specs. When it’s shipped back, he paints it. An interesting issue, he said, is that the sculptures sometime lack orientation: how do you hang/mount a sculpture designed in 360 degrees that looks good from all sides?

His favorite artists are the ones who inspired him in his formative years.

"I like most artists. I still love the artists I grew up loving. For me there’s nothing quite like Barnett Newman, Jasper Johns, and Klein and de Kooning. They still look great to me."

He produces prolifically regardless of his popularity, which has ebbed and flowed over the decades.Today Stella’s tide is rising. In 2009, President Obama hung the National Medal of Arts around his neck. A major retrospective being organized for 2014 is scheduled for three venues. And in three weeks, he’ll receive the Lifetime Achievement Award from the International Sculpture Center.

Contact Tahree Lane at 419-724-6075 and tlane@theblade.com.