Minority poetry inspires call to action

Speakers in Toledo recall heritage seldom taught in school

9/23/2013

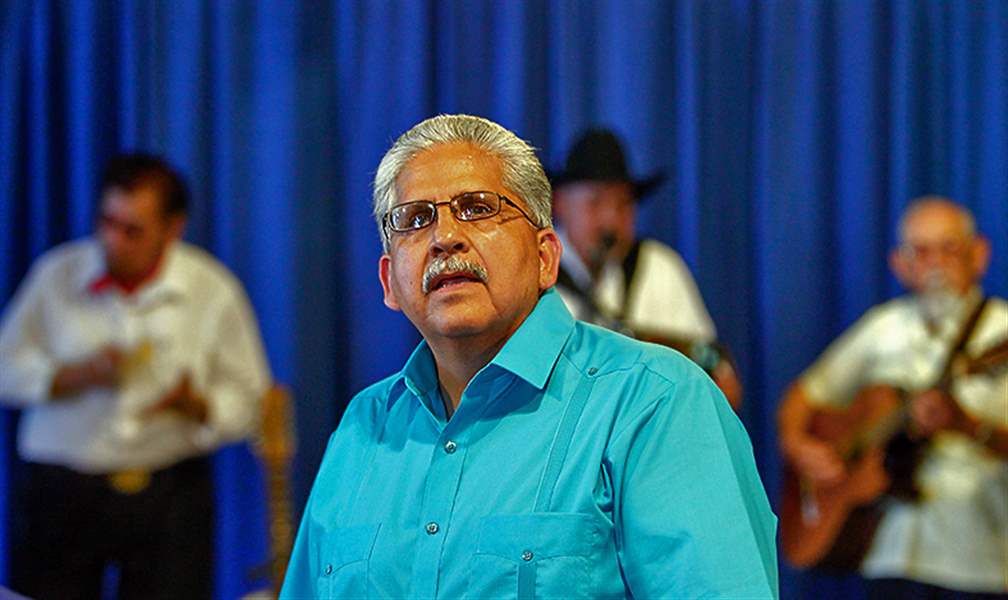

Toledo poet Manuel Caro, 62, appears at the Sofia Quintero Arts & Cultural Center before a crowd of 500. The audience responded to his recitation with cheers, applause, and arms and fists thrust into the air.

The Blade/Andy Morrison

Buy This Image

Toledo poet Manuel Caro, 62, appears at the Sofia Quintero Arts & Cultural Center before a crowd of 500. The audience responded to his recitation with cheers, applause, and arms and fists thrust into the air.

He stood quietly, not moving behind the podium. A dim reading light made his face glow faintly in the dark.

Toledo’s Manuel Caro gave no indication he was aware that there were 500 people gathered at the Sofia Quintero Arts & Cultural Center eagerly awaiting his first public performance in nearly two decades.

Once Mr. Caro, 62, had been a well-known, respected Chicano poet and an outspoken civil-rights leader.

RACE IN TOLEDO: Changing minds, changing lives

Like many Mexican and African-Americans in the late 1960s and 70s, they had used poetry and prose to speak out about racism, educate their communities about their heritage and culture, and to make their people aware of their considerable, but often ignored contributions and accomplishments.

A longtime university professor and administrator, he spent his career fighting for better educational opportunities for people of color.

But by the 1990s, the Harvard-educated Mr. Caro had become frustrated and tired of fighting and rarely appeared in public.

There was no introduction this September night when he made his return. He simply began to recite a poem.

‘‘I’m sitting in my history class,

The instructor commences rapping,

I’m in my U.S. history class,

And I’m on the verge of napping.

The Mayflower landed on Plymouth Rock. Tell me more! Tell me more!

Thirteen colonies were settled.

I’ve heard it all before.

What did he say?

Dare I ask him to reiterate?

Oh why bother.

It sounded like he said,

George Washington’s my father.

I’m reluctant to believe it,

I suddenly raise my mano (hand).

If George Washington’s my father,

Why wasn’t he Chicano?’’

The audience, ranging from young teens to senior citizens, burst into cheers and applause. Many rose to their feet and thrust their arms and fists into the air — a symbol of solidarity and support and a gesture that many Chicano and African-American civil-rights activists used to demonstrate their resistance and defiance to a white power structure they believed was intent on oppressing them.

“It’s so good to see Manuel Caro back,” said event attendee Jose Luna, Hispanic Outreach Coordinator for Toledo Public Schools. “He is one of our community’s giants.

“We need him back now more than ever.”

Ramon Perez, 57, a community organizer for United North in Toledo, agreed. Toledo’s Latino community needs veteran leaders like Mr. Caro to inspire, challenge, and share knowledge with the community’s younger generation.

The poem Mr. Caro had recited, “I’m Sitting in My History Class,” was written by Chicano poet Richard Olivas in the early 1970s.

The poem addresses how American history often distorts the country’s origins, how blacks, Native Americans, and Mexican-Americans were enslaved, exploited, and oppressed, and often ignores their very existence and contributions, Mr. Perez said.

It was issues like these that really fueled the Chicano and black power movements in the 1960s and 70s, Mr. Perez said.

Chicano and African-American poetry was a way to make their communities more aware of the racism and discrimination they were being subjected to and how negative stereotypes and historical lies were being used to keep them oppressed, he said.

“Our education system is the biggest contribution to racism,” Mr. Perez said. “Look at all the textbooks and you won’t see us, or you’ll see us in subservient roles. Where are our contributions?

“What does this tell Mexican-Americans? We’ve been relegated to savages, a second-class society.”

Mr. Perez was exposed to Chicano poetry while attending Bowling Green State University in the late 1960s. As a student, he was involved with the Latino Student Union, which often invited famous civil-rights activists to campus, including Stokely Carmichael, Russell Means, Angela Davis, and Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzales.

It was Mr. Gonzales’ poem “Yo Soy Joaquin (I Am Joaquin)” that proved to be a revelation for Mr. Perez.

Poet Melvin Douglas Johnson, 73, of Toledo performed in late 2011 at an event in the city. He says writing poetry helps him 'put things in perspective.'

‘Our history’

“When Corky started reading he was telling us our history,” said Mr. Perez, who ended up becoming friends with the famous activist. “That one poem explained how our history had been rewritten by whites to show how they had established and done everything.”

The poet encouraged the young Mr. Perez to become more involved in the Chicano power movement. He also became involved with a then-fledging Toledo organization called the Farm Labor Organizing Committee, whose mission was to fight for the civil rights of farm workers.

Chicano poetry introduced Mr. Perez and other Mexican-Americans to parts of American history that had mostly gone ignored. What he discovered outraged him:

The young Mr. Perez learned about the forced expulsion during the 1930s of 1.5 million Mexican-Americans — U.S. citizens — something that’s never included in textbooks or discussed in history classes, he said.

He discovered that Mexican-Americans were frequently lynched just like blacks, but those lynchings were often ignored by the media, he said. During the 1930s, there were 600 recorded lynchings of Mexican-Americans in America.

Melvin Douglas Johnson, 73, of Toledo, remembers the day his uncle left for World War II. His family had discouraged him because blacks were still treated like second-class citizens in the military, they said.

The young Johnson watched as his uncle and other black recruits were forced to stand aside and wait until all the white recruits were loaded up first.

The memory prompted Mr. Johnson to write one of his first poems, “How Could You,” which questioned how the military could be so blatantly racist toward men who had volunteered to give their lives to defend America.

“The poetry I wrote was reflective of the racism that was in existence,” said Mr. Johnson, who continues to perform across the country. “It helps me put things in perspective.

Like the Curtis Mayfield song “Black is a White Man’s Word,” African-American poets used words to help their community understand the importance of defining themselves and dispelling the negative images and stereotypes white America had created about them, Mr. Johnson said.

Mr. Johnson, whose influences include poets and activists such as Amiri Baraka, Nikki Giovanni, and Dayton’s own Paul Laurence Dunbar, is an accomplished author. He’s published three books of poetry and one CD.

Luis Chaluisan, 55, of Bowling Green is a longtime poet, retired TV show host for Telemundo, and professional salsa musician.

Bold messages

By the early 1970s, new poets like Gil Scott-Heron, the Last Poets, and the Watts Prophets were combining spoken word poetry with jazz and delivering bold new messages.

Their works were dripping with anger, bitterness, and sarcasm, reflecting the broiling emotions many Chicanos and blacks were feeling at the time, said Luis Chaluisan, 55, a longtime poet, retired TV show host for Telemundo, and professional salsa musician.

“Groups like the Last Poets connected with people because they were illustrating how we were feeling inside,” said Mr. Chaluisan, a Puerto Rican who grew up in New York’s South Bronx. “It grew out of our culture.

“The combination of poetry and music seemed like a natural fit.”

Mr. Johnson and Mr. Chaluisan, who now lives in Bowling Green, don’t think poetry is losing popularity with today's youth. Its popularity is more obvious in larger cities, they say.

Poetry evolving

If anything, poetry is evolving, they agree.

The evolution includes the merging of poetry and hip hop, said Chicago native Naek Ankh. The poet has spent the past decade performing all over the world, including South Africa, where she introduced the new style to an appreciative crowd.

The style merges spoken word poetry with hip-hop, an infectious blend that when performed in an upbeat manner invites a call and response interaction with the audience.

There’s a big difference between hip-hop and rap, Ms. Ankh is quick to explain. Hip-hop is, and always has been, about positive, uplifting lyrics and messages. Rap tends to focus on drugs, gangs, and other negative aspects, she said.

Like many of today’s younger poets, she discovered poetry through the word play found in hip-hop lyrics. As a preteen, she was inspired by her older brother’s NWA and Public Enemy records, groups which delivered political and self-empowerment messages, she said.

By the time she was 11, she was writing poetry with two other girls, and they called themselves “Poetic Devotion.”

“I don’t remember the name of my first poem, but I remember what it was about,” Ms. Ankh said. “It was about my father and my never having had a chance to meet him.”

Her poems and music continue to reflect her life experiences, she said.

“When I was 11 years old, I wrote about what 11-year-olds imagine life is like,” she said. “Seven years ago I was writing about my experiences as a black woman.

“Now I’m working on new poems and music that reflect more spiritual matters, maturity, and storytelling. My writing is a window of what I’m going through.”

Poetry among young people is still relevant, she said. But it’s the underground artists who keep it flourishing, she said.

Toledo resident Travis Grant, 41, better known to club-goers as “DJ Big Trav” has been a longtime poetry fan and supporter. Although not a poet himself, he’s played an instrumental role in its current evolution.

A self-described, “technology geek,” Mr. Grant several years ago began experimenting and learning how to use lighting, music, and video to enhance a poet’s performance. He describes himself as a “video DJ.”

“I mix music and video,” Mr. Grant said. “While poets are doing their pieces, I can add background music or create a slideshow that will play on a screen beside or behind them. There’s so many different levels to it.”

Local event

About two years ago, local poet Lonnie Hamilton established a monthly poetry night at Our Brothers Place, a downtown lounge and eatery owned by brothers Glenn and Mike Johnson and their brother-in-law, Al Garmon. The attraction has been open for more than two years. Mr. Grant, who serves as the DJ, assists with the planning and promoting.

The poetry event, which is held in an upstairs room in the restaurant, has proven to be a hit and everyone is invited, Mr. Grant said. There is a $5 cover charge. The next event is 8:30 to 11 p.m. Oct. 18.

Contact Federico Martinez at: fmartinez@theblade.com or 419-724-6154.