Destructive forces of nature - and man

6/3/2007

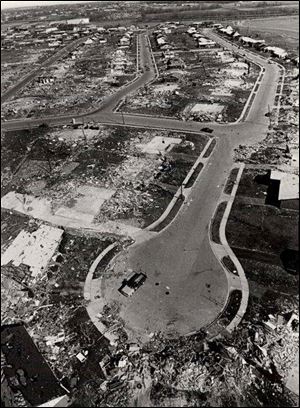

This aerial view shows the Arrowhead section of Xenia, Ohio, the area where the tornado of April 3, 1974 first touched down.

Xenia, Ohio, is 14 miles east of Dayton, and the last time I drove through it, I would have never guessed that, on an early April day in 1974, half of it blew away. It didn't strike me as vibrant or booming - though hardly dead, either. It was strip-malled blah and redundant, a consummately Midwestern town; in a police line-up, I wouldn't be able to tell it from Akron, Findlay, or Beavercreek. Which is something of a victory. As Mark Levine describes in F5: Devastation, Survival, and the Most Violent Tornado Outbreak of the Twentieth Century, the disaster that hit Xenia in 1974 did more than lay waste to 1,500 buildings, kill 34 locals, and injure 1,150 more.

It did what disasters do.

It exposed an ugliness.

If Xenia was off the map before those tornadoes, it was forgotten by the national press as quickly (and cruelly) as a week later. If quaint small-town living appeared to be on life support in 1974, the tornado accelerated the process. And if there was an economic disparity before the disaster, Levine writes that the town leaders used the tornadoes as an opportunity to push through urban renewal plans, bulldozing older homes of low-income residents who "learned that raised voices could not stop wrecking crews." But what didn't change much were those locals.

Levine's book is not about Xenia; as he mentions, rightly, that disaster has been well-documented. Instead, it's about the wider picture, the unprecedented outbreak that spawned 148 tornadoes on April 3, 1974, across 13 states in the Midwest and into Canadian provinces, killing 335 people and destroying 27,000 homes - the deadliest weather disaster in United States history until Hurricane Katrina. But even in the hardest-hit towns, the places where tornadoes land again and again, if you lived there before a tornado, chances are you stayed there after. It's a curious detail at the heart of F5: As counter intuitive as it seems, disaster does not drive people away from a place but gives them a reason for staying. Or rather, it's a point I wish Levine's uneven but unquestionably compelling history handled in more than a glancing fashion.

Levine, a fine magazine writer whose name will be familiar to readers of Outside and New York Times Magazine, has a gift for writing in the moment, for recreating scenes, but he proves creakier with the context, and the result is a rangy work. His centerpiece, the outbreak itself, is as harrowing and visceral as the best contemporary survival journalism. (Think Into The Wild.) But his stabs at vast, universal themes are embarrassing: "Destruction is an event; death is a fact; disaster is a state of mind." Ugh. And the endless attempts at linking the American zeitgeist in 1974 to the tornado outbreak are even stranger - "Nineteen seventy-four in America, half in love with death," he writes, and a few pages earlier, he calls disruptive forces the "spirit of the day," launching into a page and a half about the short-lived fad of streaking. To say Levine is overreaching is an understatement.

My guess is he'd use the Moby Dick Defense - the boiling of whale blubber and the lengthy digressions into whaling minutiae worked just fine for Melville. But the point only obscures the real accomplishment - Levine's ability to paint his white whale. He gives the tornado a heartbeat: "The tornado builds itself, leaping out of invisibility and then returning to it ... The tornado is a sculptural marvel, simultaneously solid and sheer, compact and monstrously enlarged. It seems to inhale the earth." I've never seen a real tornado but after that description, I feel I have.

Even better is the tornado lore. There's a little on the Palm Sunday disaster of 1965 that claimed 15 lives in the Toledo area, but one reason it did proves enlightening: For decades, meteorologists intentionally refused to warn about tornadoes. By the 1960s, they would at least use the word "tornado." But as Levine explains, as late as the '50s, congressmen were publicly linking tornadoes with nuclear testing in Nevada; a culture remained that presumed the panic brought on by tornado warnings was worse than the thing itself.

Not that it always matters.

Early last month the small town of Greensburg was wiped almost entirely off the face of Kansas. As in 1974, an F5-category tornado touched down, but with now ample warning, and therefore a fraction of the loss of life. In 1974, six F5 tornadoes and a couple of dozen F4s spun across the Midwest. Those categories were named for the Japanese physicist Tatsuya Fujita, and there's an anecdote in F5 that not only a history of the tornado in miniature, it's more telling than reams of social context: Surveying the 1974 damage, Fujita grew excited by the extent of the evidence available - we would learn so much about tornadoes now. In a Louisville diner, he proposed a toast, until an assistant stepped in and said:

"People died around here."

Then he got serious again.

Contact Christopher Borrelli at: cborrelli@theblade.com

or 419-724-6117.