George W. Bush delivers an unexpectedly engrossing memoir

11/13/2010

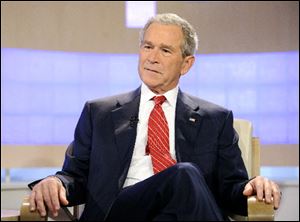

Former U.S. President George W. Bush appears on the 'Today' show Wednesday to talk about his new book, 'Decision Points.'

The first great American autobiographies both appeared in the 19th century, were born of conflict, and written by public men -- The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass and The Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant.

Since then, what we might call the publishing-industrial complex has turned the reminiscences of our public men and women into a never-ending stream. As former President George W. Bush -- barely two years out of office -- points out in the acknowledgement of his memoir, Decision Points, virtually every member of his extended, very political family has published a bestseller, including his parents' dogs.

Where does Bush's account of his astonishingly eventful eight years rank in such company? Probably far higher than many of his detractors expected. As Bush writes in Decision Points, he enjoys surprising those who underestimate him. As the title suggests, the former chief executive elected to abandon the usual chronological approach to these volumes (except for a brief, obligatory foray into childhood and school years) in favor of his recollection of his presidency's key choices and the personal decisions that Bush says prepared him to make them.

Foremost among the latter were his conversion to active Christianity, which he attributes to an after-dinner talk that evangelist Billy Graham gave to the extended Bush family at their Maine compound, and to participation in his male friends' Crawford, Texas, Bible study group.

Bush credits his religious awakening, along with a growing sense of obligation to his wife and daughters, with his other foundational personal choice: the decision to quit drinking after a night of boorish overindulgence in celebration of his 40th birthday. It's a change Bush credits with making possible his subsequent public life.

Leaks and an active publicity campaign of television and radio appearances have made many of the substantial points Bush makes rather familiar. Essentially, Decision Points confirms many of the better nonfiction accounts of his presidency published while he was in office, particularly Bob Woodward's four volumes and Robert Draper's Dead Certain. The Bush White House may not have been given to doubts or its chief executive to indecision, but it did have a penchant for ad hoc deliberation, stubborn persistence in the face of failure -- as in Iraq up to the surge -- excessive personal loyalty, and for being "blind-sided" by events beyond the unforeseeable tragedy of 9/11.

Nearly midway through Decision Points, Bush writes that, "History can debate the decisions I made, the policies I chose, and the tools I left behind. But there can be no debate about one fact: After the nightmare of September 11, America went seven and a half years without another successful terrorist attack on our soil. If I had to summarize my most meaningful accomplishment as president in one sentence, that would be it."

For that reason, Bush is singularly unapologetic and clear about the fact that he personally ordered the torture of key al-Qaeda members, who CIA interrogators were convinced held information of other planned terrorist attacks. (Bush also continues to insist that waterboarding is not torture.) When then-CIA Director George Tenet asked whether he had permission to waterboard Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, the 9/11 mastermind, Bush replied, "Damn right." Bush writes that about 100 "terrorists" were placed in the CIA interrogation program and that about a third "were questioned using enhanced interrogation;" three were waterboarded. All, according to Bush, gave up usable intelligence that thwarted other acts of terrorism. Other reports have contradicted that assertion, but Bush is firm on the point.

Similarly, he writes that his stomach still churns over the fact that he and the rest of the country were misled by faulty intelligence concerning Saddam Hussein's pursuit of weapons of mass destruction, but that the nation and world still are better off with the Iraqi dictator deposed. His only real regret, in fact, is that he failed to act more rapidly and decisively when Hurricane Katrina devastated New Orleans.

Many readers will be surprised by Bush's warm account of his cooperative relationship with the late Sen. Edward Kennedy and his disappointment that they were unable to push through comprehensive immigration reform, which both felt was within a vote or two of their grasp.

Given the contentious political use Karl Rove and other Bush aides made of abortion, readers also may be interested in the former president's unfailingly respectful discussion of the abortion-rights advocates with whom he disagrees. (There's also something amusing about Bush's account of urging the late Pope John Paul II not to waver in his pro-life convictions.)

Actually, one of the impressions that arises repeatedly in Decision Points is how much civility and bipartisan cooperation matter to Bush. "The death spiral of decency during my time in office, exacerbated by the advent of 24-hour cable news and hyper-partisan political blogs, was deeply disappointing," he writes.

Looking back on his exit from office, Bush recalls, "I reflected on everything we were facing. Over the past few weeks we had seen the failure of America's two largest mortgage entities, the bankruptcy of a major investment bank, the sale of another, the nationalization of the world's largest insurance company, and now the most drastic intervention in the free market since the presidency of Franklin Roosevelt. At the same time, Russia had invaded and occupied Georgia, Hurricane Ike had hit Texas, and America was fighting a two-front war in Iraq and Afghanistan. This was one ugly way to end the presidency."

There's a great deal in that statement of what this unexpectedly engrossing memoir suggests is the essential George W. Bush -- a disarming candor, for example, combined with almost alarming off-handedness about the implications of what's being said. The man and the president portrayed in these pages is, at the same time, passive and strong, intelligent but not curious, a public person apparently at his best in private, willing to admit shortcomings, but not particularly self-critical, unfailingly civil himself, but happily surrounded by bare-knuckle partisans. There is a kind of pragmatic courage that makes a leader fearless of contradictions. Bush, for his part, seems oblivious to them.